Private collection

The Pearl of Asia, an adventurous life

Pour lire cet article en français, veuillez cliquer ici.

Claudine Seroussi Bretagne

Gemstones often live adventurous lives – none more so than the Pearl of Asia.

At approximately 605 carats, and measuring 76 x 50 x 28 mm, it is the largest nacreous pearl in the world. A photograph taken in 1945 gives a sense of the scale of the pearl.

The large egg-shaped pearl was renowned not only for its size but also its silvery colour and a lustre that “provides a mirror for one’s whole face.” Mounted in a gold setting in a bunch of fruits style with a jade cabochon, smaller pearl and rose quartz representing other fruits, it is reminiscent of 16th and 17th-century designs despite being executed [possibly in Europe] between 1900-1930

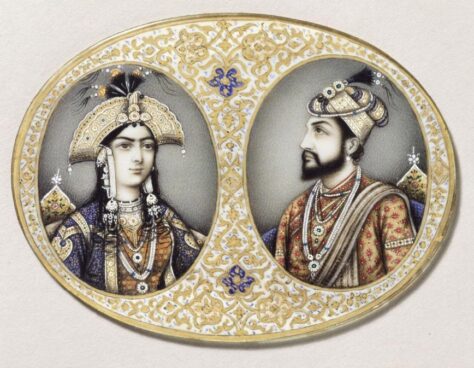

The pearl first appeared in 17th-century India and is believed to have originated from the Persian Gulf. It was purchased in Bombay by the agents of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (1592-1666), who was renowned for his vast jewellery collection that included the Koh-i-Nor and whose court was famed for its extravagance, great pomp and pageantry.

Shah Jahan gifted the pearl to his second and favoured wife, Mumtaz Mahal (1593-1631).

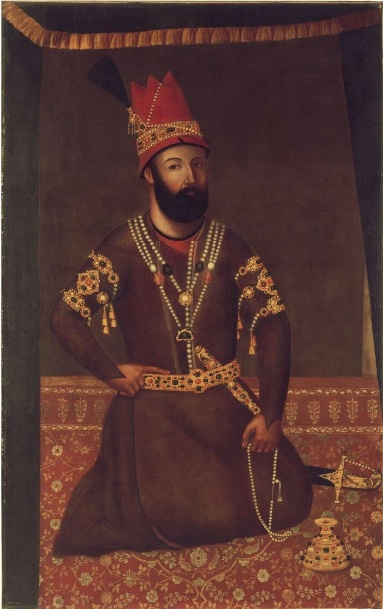

After his death, the pearl was passed through the hands of lesser Mughal Emperors. In 1739, Nader Shah of Persia (1688-1747) defeated the Mughal army and seized Delhi, the capital, as well as the Mughal emperor’s jewels, including the Pearl of Asia.

Nader Shah gifted several jewels that he seized from the Mughal empire to other sovereigns including Catherine the Great and Sultan Mahmud of the Ottoman Empire. To the Chinese Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), he gifted the Pearl of Asia. Qianlong considered the pearl a valuable possession, so much so that it was placed in his mausoleum upon his death.

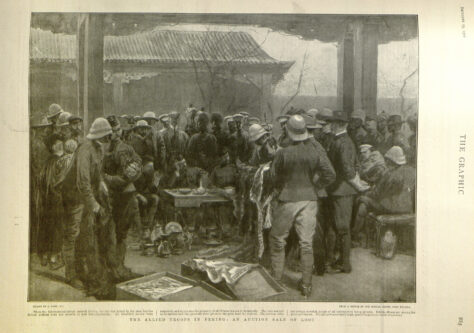

During the bloody boxer rebellion of 1900, alongside the executions and pillages, extensive looting of Peking was committed by all the forces of the 8-nation alliance (France, Austro-Hungary, Italy, Russia, Germany, Britain, USA and Japan). The British Army regulated the looting by holding daily auctions, except Sundays, at Protestant and Catholic Churches. These auctions were always crowded and attracted people of all nationalities.

Qianlong’s tomb was subjected to looting, and the pearl once more disappeared. The pearl resurfaced in Hong Kong some years later when a mandarin sold it to a French missionary, and it became the property of the French Foreign Missions Society of Paris (MEP).

1930 marked the first failed attempt by the MEP to sell the pearl in partnership with the pearl’s co-owner, Major Mohideen, a Singaporean gem dealer. It was placed for sale in Shanghai, with an asking price of $1,500,000. Mohideen stated that he lived in seclusion, fearing being kidnapped and forced to relinquish the jewel.

In 1942 it resurfaced again and was finally sent to France to be sold as the Missions urgently needed to raise money. The pearl arrived in Paris and was shown to various jewellers with a price tag of approximately $150,000. However, the Germans became aware of the existence of the pearl and forced the MEP’s emissary to deposit it in a bank until permission was granted to remove it. At one stage, Goering showed interest in adding it to his collection, but nothing came of it.

In 1944 the MEP tried once more to sell it. A buyer was found, and a viewing appointment was arranged, during which four “SS men” burst into a room where the French experts were examining the pearl and took the pearl, its gold case and valuables worth 15,000 francs of other valuables at gunpoint. They claimed that the MEP had no right to sell the pearl, and they took off with it. The culprits were not SS men but Yvon Collette, his wife Georgette and three associates. They were arrested and questioned but denied knowing where the pearl was. With all leads having gone cold, it was assumed the pearl had left France.

With the liberation of Paris, the Collettes managed to escape custody. Yvon fought in the siege of Paris, and Georgette returned to Marseille, where she removed the pearl from the Oak tree where she had hidden it in 1944 and awaited Yvon’s return. Yvon tried to sell the pearl after the allied landings but could not find a buyer. He was arrested once more, and the pearl was eventually discovered by a hotel landlord in an overflowing toilet in Collette’s room, where she had hidden it during a police raid.

During the 1945 trial, Collette and his accomplices claimed that they were members of the Resistance and said that they had taken it to stop it falling into the hands of Goering, who coveted the pearl.

Collette said he wanted to present it personally to Charles De Gaulle. The theft and subsequent trial garnered press coverage across the world. Yvon, a Belgian national, was both a member of the Resistance and a German collaborator and although it remains unclear where his allegiances lay, this theft was undoubtedly self-serving. The trial was postponed in November 1945 so Collette could round up resistance leaders to support his claims.

By the time the trial reopened in May 1946, Yvon, deemed mentally unstable, was placed in a mental hospital for observation and from which he staged an audacious escape (he gnawed his way through a straitjacket). He was sentenced, in absentia, to 10 years imprisonment and a fine of 50,000 francs. Collette and an accomplice were sentenced to 2 and 5 years for their complicity in the crime.

And the Pearl of Asia?

The MEP reclaimed the pearl in 1945, and it was again put up for sale, this time for $500,000. It is unclear when it finally sold and to whom. In 2005 The Pearl of Asia was one of the world’s twelve rarest pearls, which went on public display for the first time in the “Allure of Pearls” exhibition held at the NMNH of the Smithsonian Institution. Although Christie’s facilitated the anonymous loan, it was reported that the Pearl of Asia shared the same owner as the Hope Pearl – a private collector based in England.

It remained in private hands and was last seen in public at the V&A’s 2013 “Pearls” exhibit.

***

Follow her on her wonderful Instagram account :

Instagram @ Art of the Jewel

The Guy Ladrière Collection of engraved gemstones : intaglios, cameos and rings

Pour lire cet article en français, veuillez cliquer sur ce lien.

Interview with Guy Ladrière, the Prince of Rings

I met with Guy Ladrière at Quai Voltaire for an interview about his private collection of glyptics - the ancient art of engraving gems- which will be exhibited from May 12 to October 1, 2022 in Paris at the École, School of Jewellery Arts.

The Ladrière Collection unites the eye and the exquisite taste of a man, a passionate expert: Guy Ladrière. Remarkable in many ways, his collection embraces a vast geographical area (Asia, Africa and Europe) and covers nearly three millennia of the art of glyptics. Eclectic, it gathers today more than four hundred pieces of which the majority are rings. Except for the most fragile, the collector wears them on his fingers every day.

Today he is wearing a rare ruby intaglio set in a heavy gold ring on his right finger. Touchingly, the engraved gemstone depicts the Virgin Mary carrying the baby Jesus and gazing at him. The image is reminiscent of the gothic sculpture of the Virgin Mary nursing her Child in the Cluny Museum or the Louvre. On the ruby intaglio, the Virgin Mary and Child are closely sheltered by what appears to be an oratory or small chapel.

For forty years Guy Ladrière has collected intaglios (stones engraved in hollow relief) and cameos (stones which, because they have superimposed layers of different colors, are engraved in relief and respond in miniature proportion to ancient bas-reliefs, monumental Greco-Roman sculptures and medieval polychrome woods).

Set on rings, brooches and pins, glyptic art put into image the vast panorama inhabited by the Egyptian, Greek and Roman pantheon gods, populated by Homeric or Ovidian characters, figures of temporal power, sometimes from the Bible, and various animals escaped from the fables of Aesop. When one stops to observe this multitude of details finely engraved by slow abrasion of the stone, one would feel time stop.

Engraved stones carry multiple meanings: A distant echo of the beginnings of writing (intaglio, cylinder seal, seal); material witness to commercial exchanges and daily agrarian concerns; a reminder of beliefs and the understanding of the world; a tribute to illustrious men; and finally a luxury object made into an ornament.

Starting from his interest in ancient rings, Guy Ladrière felt the desire to build a collection.

From his first acquisitions at Jean-Philippe Mariaud de Serres or at S.J. Phillips in 1976 during the exhibition of the Ralph Harari collection, he relied on one criterion: the quality of the object.

“I buy it because I like it”, he says casually. Figures of Zeus, Aphrodite, Cupid, Mercury, muses and Medusa heads (more than a dozen!) compete for predominance in the Collection with representations of heroic subjects, imperial portraits and animal themes: bulls, felines, galloping horses, eagles, snakes... etc. There is even a cameo in the form of a sardonyx “the Marvel of Lisbon”, a singular rhinoceros which was the second of its kind to be sent from India to Europe in 1577.

“I like everything, I'm interested in everything, as long as it's beautiful”, he says. The collector does not adopt an encyclopaedic or systematic approach but favours the appearance and quality of the object. Thus, Guy Ladrière owns a few Caesars but do not consider it useful to collect the Twelve.

One of the most extraordinary pieces of the Collection is the intaglio with the effigy of Augustus (63 BC -14 AD). A translucent Burmese ruby weighing 15 ct “in the shape of a half bean”, this irregular oval cabochon of a luminous pink-red is deeply engraved, on its flat part, with the profile of the first Roman emperor (whose countertype reveals the left profile).

“Forma fuit eximia et per omnes aetatis gradus uenustissima”. He was extremely handsome and gracious throughout his life, wrote Suetonius in the Life of the Twelve Caesars (II,79). It is undeniable.

It is nevertheless surprising to note that on this ruby, the Emperor is represented neither under divine features, nor according to the canons of the Greek ideal; his face is marked by the wrinkles of the naso-labial fold and a nasal hump which accentuates his “aquiline and fine” nose. The engraving appears to be of authentic precision. From this striking profile emanates an impression of solemnity and grandeur. It is hard to take your eyes off it. It is now considered almost certain that the glyptician who created this masterpiece was a Greek contemporary of Augustus, who lived in Rome in the first century and whose name appears in the pantheon of the most famous glypticians: Dioscorides.

Guy Ladrière remembers how fascinated he was by the sight of the gold ring enhanced with the countertype of the Augustus intaglio worn by the Parisian dealer Michel de Bry. In 1989, the intaglio was for sale at an auction in Paris. Without hesitation, Guy Ladrière snatched the bid. Since then this intaglio, which served as a seal to Augustus and which Suetonius says that “this last seal was the one that the princes - his successors - continued to use” (Life of the Twelve Caesars, II, 50), forms the beating heart of the Ladrière Collection.

There are no major steps in the constitution of the Collection because Guy Ladrière buys at public sales, from established dealers or antique dealers (Codognato, Sam Fogg, S. J. Phillips, Adrien Chenel) at a regular pace. If glyptics remain his favorite field, he also collects hard stone vases and medals. Sometimes he acquires several engraved gems in one go. Thus the four heads of “Medusa” acquired in Milan from the collection of Giovanni Pichler (1734-1791) or Luigi Pichler (1773-1854), rich in treasures.

Naturally, when one traces the historical provenance of the most famous intaglios or cameos, one is struck by the lineage of illustrious collectors who have succeeded one another. Whether in Antiquity, in the medieval West or during the Renaissance, the most beautiful engraved gemstones, those with exceptional technical virtuosity, have been constantly reused because they have always been considered precious, and therefore sought after by great people: sovereigns, aristocrats, high clergy. Without pose or snobbery, with aplomb even, Guy Ladrière admits “it does not influence me when I am told that an object comes from so-and-so”. But of course, the provenance of a piece of great beauty increases the prestige of the object.

Thus, this Renaissance cameo all in volutes with the profile of Semiramis (or allegory of the moon) which belonged to the most important collector of antiquities of the eighteenth century, the Cardinal Alessandro Albani (1692-1779), or this impressive “ring of Fridays” preciously kept by the pious king of France Charles V (1337-1380) and in the oval is inscribed a scene of crucifixion uniting around Christ, the Virgin, St. John and two cherubs leaning on the cross. When Guy Ladrière acquired this important piece, he compared it to the engraved gemstones in the collection of Frederick II Hohenstaufen (1194-1250).

Among the engraved stones of the Collection that refer to royalty (Elizabeth I of England, Philip II of Spain) and to the history of France (René d'Anjou, François I, Anne of Austria), I particularly like the cameo in sardonyx on a red background of Louis XIII (1601-1643). The bust, noble, is presented in his right profile. With wavy hair and a laurel crown, a crooked moustache and a pointed goatee, the young king is clasped in a ruff collar, a delicately chiseled armour on which rests a thick ribbon with the Maltese cross, emblem of the Order of the Holy Spirit. The engraving, although academic, is imposing and of great finesse. The cameo is enhanced by the elegance of the setting: four fine pearls at the cardinal points between which alternate old-cut diamonds framed in gold and palmettes motifs. A royal portrait through and through.

The “scientific” work is secondary for the collector. Glyptic pieces are rarely dated or signed, and their origin is often difficult to determine. Guy Ladrière, through observation, experience and consulting specialized books as well as assiduous visits over the years to Parisian museums (Cabinet des médailles de la BnF, Musée de Cluny, Louvre) and European museums (British Museum, Museo archeologico di Napoli, Palazzo Pitti, Kunsthistorisches Museum), has acquired great knowledge and rare expertise.

When he makes an acquisition, he relies on a first idea. After obtaining the piece, he says, “I then study it thoroughly: time, place where it was created, material, subject.” Guy Ladrière surrounds himself with specialists to study his pieces. Reading, deciphering, analyzing, understanding the work of glyptics requires a varied culture. It is not a prerequisite to be a gemologist, art historian, antiquarian or glyptician, but ideally, you should be a little of all of these at the same time! Do ancient sculptures help in the recognition of figures or themes on glyptic works? “It is often the numismatists who recognize the portraits in glyptics" replies Guy Ladrière.

When Guy Ladrière bought the astonishing gold ring engraved with a porcupine, he had an idea of its origin, having knowledge of the personal emblem of Louis XII (1462-1515) (Cf Ecu with the porcupine of Brittany of Louis XII preserved in the Carnavalet museum). However a mysterious motto written in retrograde “temps je attens" ("time I wait”) on the head of the ring and in the ring intrigued him, without being able to guess completely the meaning. A medieval historian friend solved the enigma, exposed by Philippe Malgouyres in his catalogue raisonné. Louis XII longed for his wife Anne of Brittany to give him an heir...

Guy Ladrière often gives thanks to his mentor, Charles Ratton (1895-1986), who was an expert, dealer and collector. “I owe him everything” he says without ambiguity. It was a common passion for the Middle Ages that initially brought them together. Moreover, even today, when we ask Guy Ladrière about a favorite period among all, he admits: the Carolingians. The irony is that “we find ivories and Carolingian manuscripts but no rings”!

The history of art in the twentieth century has especially remembered the name of Charles Ratton for the major role he played with his contemporaries in the knowledge and dissemination of the arts of Africa, the Americas and the Pacific. He is, as Guy Ladrière reminds us, the only dealer to date to whom a public institution, the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, has devoted an exhibition. It was in 2013, under the title: Charles Ratton, the invention of “primitive” arts. For fourteen years, Guy Ladrière worked alongside him, joining forces with him late in life (in 1984). As a “spiritual son”, he acquired Charles Ratton’s archives, his “personal museum” and his office, all of which he keeps intact between the Rive Droite and his Parisian apartment.

Enemy of socialites, sometimes gruff when it comes to keeping away the curious, but prolix, benevolent and warm in his inner circle, Guy Ladrière is recognized by his peers who appreciate his “eye”. In 2016, about sixty pieces of the Collection were presented for the first time at the London gallery Sam Fogg, a specialist in the art of the European Middle Ages. The event was accompanied by the publication of a first book, The Guy Ladrière Collection of Gems and Rings, edited by the renowned Diana Scarisbrick, with Claudia Wagner and John Boardman (Philip Wilson Publishers in association with The Beazley Archive, Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford, 2016).

This year, for L'École des Arts Joailliers, Philippe Malgouyres, chief curator of heritage in the art department of the Louvre and curator of the Pierres gravées exhibition, is dedicating an excellent book to the Ladrière Collection published by Mare & Martin under the title Engraved gemstones. Intaglios, cameos and rings from the Guy Ladrière collection. He also co-published with the École a special issue of Cameos and Intaglios: The Art of Engraved Stones - Découvertes Hors-Series Gallimard .

To the eye of the collector are added the crossed views of Philippe Malgouyres and an “engraver-sculptor on hard stones and fine stones”, Nicolas Philippe, within the exhibition orchestrated by l'Ecole, School of Jewelry Arts. These are precious clues that will be offered to visitors who have come to contemplate these unique masterpieces of glyptics, and to learn about an art that has become so rare today.

***

L’École des Arts Joailliers

31, rue Danielle Casanova, 75001 Paris. France.

Tel. + 33 1 70 70 38 40

Exhibition from 12 May to 1 October 2022

Open from Tuesday to Saturday, from 12pm to 7pm

Free admission, by reservation

Reserve your time on www.lecolevancleefarpels.com

Guy Ladrière, a very special collector ... in Paris Diary by Laure

Medusa. Cameo in sardonyx on a gold brooch. With the courtesy of Guy Ladrière. Photo Didier Loire.

The mystery of the Cartier-Linzeler-Marchak box

To read this article in French please click here

by Olivier Bachet

This article was born from a purchase. One day, my Partner came back from the USA with a beautiful object in his pocket: A gold Cartier cigarette case adorned on both sides with extraordinary Persian hunting scenes, probably inspired by a page of a Persian manuscript, and made in delicate mother-of-pearl and hardstone inlays by Wladimir Makowsky, the master of jewelry marquetry of the Art Deco period.

This box was signed “Cartier Paris Londres New York”, but it also bore a mysterious mention: "incrustations de Linzeler Marchak" (inlays by Linzeler Marchak). It was curious, to say the least, to find a double signature on an Art Deco box.

To my knowledge, Cartier and Linzeler-Marchak did not work together. Another enigma was then added to the first. I knew the jeweler Linzeler more for goldsmith's pieces rather than for jewelry and Marchak more for his post-war creations and, in particular, his big "cocktail" rings rather than his Art Deco creations, but I had only very rarely seen the association of the two names on a pièce. And suddenly, I remembered that most of the silver pieces made by Cartier in the 1930s bore the maker’s mark of Robert Linzeler. There were a lot of such pieces, because if, for the common people, Cartier is a jeweler above everything else, a very important part of the sales during the Art Deco period was represented by silverware, in particular, table silver, household silver, centerpieces, torches, etc... At the time, I was doing research for the book I was writing with Alain Cartier, Cartier : Exceptional Objects. It was therefore time to put a little order in all this to see more clearly and to understand the relationship between three famous names in Parisian jewelry: Linzeler, Marchak, and Cartier.

Gold, lapis-lazuli, enamel, mother-of-pearl marquetry.

Signed Cartier Paris Londres New York.

Incrustations de Linzeler-Marchak.

L: 8.7 cm; W: 5.4 cm; H: 1.3 cm.

Private collection.

Robert Linzeler was born on March 9, 1872. He descended from a dynasty of jewelers-goldsmiths who had been settled in Paris since 1833. In 1897 he moved to 68 rue de Turbigo, when he bought the workshop of Louis Leroy. By the same occasion, he registered his hallmark of master goldsmith on April 14, 1897. It consisted of the two letters R and L surmounted by a royal crown. As tradition among the French jewelers, this hallmark takes the symbol of the hallmark of its predecessor, i.e. a royal crown. One could believe considering the name of Leroy ("the king" in French) that this symbol was chosen by the latter because in general the symbols were chosen according to puns referring to the patronymic of the manufacturer, but in reality, this symbol was that of Leroy's predecessor, Jules Piault, a goldsmith who specialized in the manufacture of knives whose workshop in the rue de Turbigo had been bought by Leroy in 1886.

The mention « succr. » after the name is the abreviation of the word « successeur » (successor).

Another amusing detail, he specifies under his address "near Saint Augustin", that is to say near the church of Saint Augustin. At a time without GPS, this allows customers to immediately locate the street and above all to show that the workshops are located in a chic neighborhood, contrary to the tradition of Parisian jewelry and goldsmith workshops which, historically, are located in the Marais district, now one of the most expensive areas of Paris but at the beginning of the twentieth century, very popular, which was the case of Linzeler when he moved in 1897 rue de Turbigo.

Business was flourishing because in April 1903, Robert Linzeler left rue de Turbigo and acquired a 480 m2 mansion located on rue d'Argenson in the luxurious 8th arrondissement of Paris to set up both his workshop and a showroom to receive private customers.

This period before the First World War was a fertile one.

The genius Paul Iribe, who also had Cartier as a client and for whom he made silverware, designed jewelry for Linzeler, as Hans Nadelhoffer points out in his book, Cartier Jewelry Extraordinary. He was, therefore, as often was at the time, both a manufacturer for others and a retailer for himself.

After the Great War in December 1919, the company was renamed ROBERT LINZELER-ARGENSON S.A. This change of name was accompanied by the installation of a magnificent store decorated by Robert Linzeler's friends, Süe and Mare, who were known for their Art Deco decoration. Unfortunately, business was poor. It should not be forgotten that the aftermath of war is a period of crisis that makes business difficult.

This is when the Marchak brothers step in.

Platine, diamonds, sapphires, pearls and emerald designed by Paul Iribe for Robert Linzeler, circa 1911.

H. 3 5/8 in. (9 cm)

W. 2 1/4 in. (5.6 cm)

D. 5/8 in. (1.5 cm)

Private Collection

Silver, portor marble. Signed Cartier. Boar's head French hallmark for silver. L: 35 cm; W: 11 cm (tray set). L: 25 cm (paperknife). L: 13.5 cm; W: 6 cm (ink pad). L: 4.5 cm; H: 6 cm (match pot).

Maker: Linzeler. Private collection.

This desk set is made in black Portor marble with yellow veins. It is identical to the marble chosen by the marble stonemason Houdot to decorate the front of the boutique on rue de la Paix in 1899. Used to decorate all of Cartier's boutiques throughout the world, this marble is often associated with Cartier.

The brothers Salomon and Alexandre Marchak, born in Kiev in 1884 and 1892, respectively, were the sons of Joseph Marchak, nicknamed the "Cartier of Kiev".

He was a jeweler and goldsmith whose high-quality production made the reputation of the company. In 1922, the Marchak brothers entered the capital of Robert Linzeler, and the company became LINZELER-MARCHAK. They signed the pieces accordingly, and it was still under this name that they received a Grand Prix at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. The company LINZELER-MARCHAK was changed to the A. MARCHAK (Société Française de joaillerie et d’orfèvrerie A. Marchak) in December 1927.

This period corresponds, I think, to the intervention of Cartier in the Linzeler case but only for the part regarding the mansion of the rue d’Argenson, because, let's not forget, Linzeler owned this mansion and the store at 4 rue de la Paix. I do not know whether Cartier had entered Linzeler's capital at the end of the 1920's, but this hypothesis is probable since in 1932, René Révillon, Louis Cartier's son-in-law, proposed to increase the company's capital and give part of it in shares to Robert Linzeler in exchange for the sale of the business and the private mansion on rue d'Argenson. The remaining shares were bought by Cartier-Paris and especially by Cartier-New York, which became the majority shareholder. This date also corresponds to the end of the association between Robert Linzeler and the Marchak brothers. It seems, therefore, that at this date, Cartier took total possession of rue d'Argenson and the Marchak brothers of the store on rue de la Paix.

The Linzeler-Marchak company was definitively dissolved on June 10, 1936. Finally, Robert Linzeler died on January 25, 1941.

Thus, from 1932 onwards, the Robert Linzeler workshop at 9 rue d'Argenson produced many silver pieces for Cartier, its new owner.

The workshop became, in a way, the workshop of the House specializing in the manufacture of silverware, especially for Cartier-New York, the owner of most of the company's capital. This explains why many pieces bear the hallmark of Robert Linzeler, not in a lozenge shape, but in a shell shape, meaning that the piece is only intended for export as is the case on this extraordinary pair of gold, silver, lacquer and glass Cartier candelabra that I was lucky enough to buy. These are now in the Lee Siegelson collection in New York. It is worth noting that it was in this vast mansion that Cartier would install the Ploujavy workshop in the 1930s, another manufacturing workshop specialized in the making of silver and lacquer objects such as cigarette boxes and vanity cases.

by silver arms to a central post of black lacquer and cut glass topped by a red-lacquer sugarloaf imitating coral, the base of silver with decorative channels enhancing the curved form; mounted in sterling silver, with assay marks

Signed Cartier, Made in France, stamped RL for Robert Linzeler

Each: 9 × 2 1/2 × 9 3/4 inches. Siegelson, New York.

With the exception of the clocks on the upper shelf, this showcase is a good example of the importance of silverware in Cartier's success, which is now almost completely forgotten.

Robert Linzeler's hallmark was definitively crossed out in 1949. On July 23rd of that year, the LINZELER-ARGENSON company became the CARDEL company by contraction of the names Cartier and Claudel. This was in reference to Marion, the only daughter of Pierre Cartier, the owner of Cartier-New York. She was born Cartier and became Claudel following her marriage to Pierre Claudel (son of the writer Paul Claudel). Linzeler's crown was preserved as the symbol on the new maker’s mark.

Finally, to answer the first riddle, why is there a “Linzeler-Marchak” signature on a Cartier cigarette case?

Gold, lapis-lazuli, enamel, mother-of-pearl marquetry.

Signed Cartier Paris Londres New York.

Incrustations de Linzeler-Marchak.

L: 8.7 cm; W: 5.4 cm; H: 1.3 cm.

Private collection.

I see only one hypothesis: The box was born Cartier. With its frieze of geometric motifs engraved on the edges without enamel, its thumbpiece, and its hardstone corners, it belonged to the series of “Chinese” cases. They were relatively little elaborate cases whose two faces were probably decorated with burgauté lacquer in the image of another specimen of 1930. Was the box damaged, or did the customer want a box with a more elaborate decoration, the mystery remains.

However, it passed around 1925, under unknown circumstances, into the hands of Linzeler-Marchak, located at 4 rue de la Paix opposite the Cartier store. It was then transformed by adding an enameled surround and two magnificent Makowsky miniatures and was signed with the mention “incrustations de Linzerler-Marchak” (Inlays by Linzeler-Marchak), but the Cartier signature was not removed.

Gold, burgauté lacquer, coral, enamel, platinum, rose-cut diamonds. Tortoiseshell backed lid.

Signed Cartier Paris Londres New York.

Eagle's head French hallmark for gold. Maker’s mark: Renault L: 8.3 cm; W: 5.5 cm; H: 1.4 cm.

Private collection.

The history of this case clearly illustrates the complexity of the relationship between Parisian jewellers and goldsmiths in the first third of the 20thcentury, where, in certain circumstances, people did not hesitate to buy back objects of competitors, add their own signature, and sell the items on their own behalf.

***

Maker’s marks

Speciality : Silversmith, jeweler

Maker’s mark : Symbol : A crown

Maker’s mark : Letters : R.L

Address : 68 rue de Turbigo, then 9 rue d’Argenson and 4 rue de la Paix, Paris

Registration date : 14/04/1897

Deregistartion date : 1949

Speciality : Silversmith

Maker’s mark : Symbol : A crown

Maker’s mark : Letters : J.L

Address : 68 rue de Turbigo, Paris

Registration date : 1856

Deregistartion date : 1887

Speciality : Silversmith

Maker’s mark : Symbol : A crown

Maker’s mark : Letters : L et Cie (the distribution of the letters in the punch is hypothetical)

Address : 68 rue de Turbigo

Registration date : 15/11/1886

Deregistartion date : 04/05/1897

Speciality : Silversmith, jeweler

Maker’s mark : Symbol : Two crosses lines

Maker’s mark : Letters : P.L.J.V

Address : 66 rue de de La Rochefoucault, then 9 rue d’Argenson, Paris

Registration date : 08/08/1929

Deregistartion date : ?

Speciality : Silversmith

Maker’s mark : Symbol : A crown

Maker’s mark : Letters : S.A.C.A

Address : 9 rue d’Argenson, Paris

Registration date : 19/09/1949

Deregistartion date : ?

***

Bibliography

O. BACHET, A. CARTIER, Cartier, Exceptional Objects, Palais Royal 2019.

M. DE CERVAL, Marchak, éditions du Regard, Paris, 2006.

Articles on Marchak and Linzeler in J. J. RICHARD, BIJOUX ET PIERRES PRECIEUSES, Blog, August 2017, February 2018

***

This article was written by Olivier Bachet for the International Antique Jewelers Association (IAJA), a consortium of antique and period jewelers around the globe. It is published on Property of a Lady with the kind permission of the author and the IAJA.