Interviews

Santi Jewels by Krishna Choudhary, an ode to Mughal jewellery

"My great desire is to tell the world about the rich history and culture of India through the story of my family.”

Krishna Choudhary represents the eleventh generation of a family of jewellers who have been practising their art in Jaipur since the 18th century. Of Hindu origin, named after one of India's most revered and popular deities, Krishna has a long-standing passion for the history of the Indian subcontinent, its ancient artefacts and especially for the decorative arts of the Mughal period (1526-1857).

After graduating from Middlesex university London, he completed his studies in Islamic history and Hindu arts at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). In 2011, he completed a degree in gemology at the Gemological Institute of America. He then returned to his hometown, Jaïpur, to train at his family's business, Royal Gems & Arts. In 2018, Krishna Choudhary moved back to London and in 2019 he opened his own jewellery house: Santi Jewels. Located in a private salon in Mayfair, Santi Jewels is characterised by elegantly understated pieces adorned with dazzling gems and multiple references to Mughal jewellery. As a whole, Krishna's creations pay homage to his father, Santi, to the jewellery tradition of his native Jaipur, and to the even more distant tradition of India. Krishna nevertheless remains a man of the 21st century. Nourished by an ancestral tradition, he manages to break away himself from it in his own creations. We met to go back in time to discover his roots, influences and artistic tastes, references that allow us to fully appreciate the refinement of his creations.

The Choudhary family, Royal Gems & Arts and the Pink City of Rajasthan

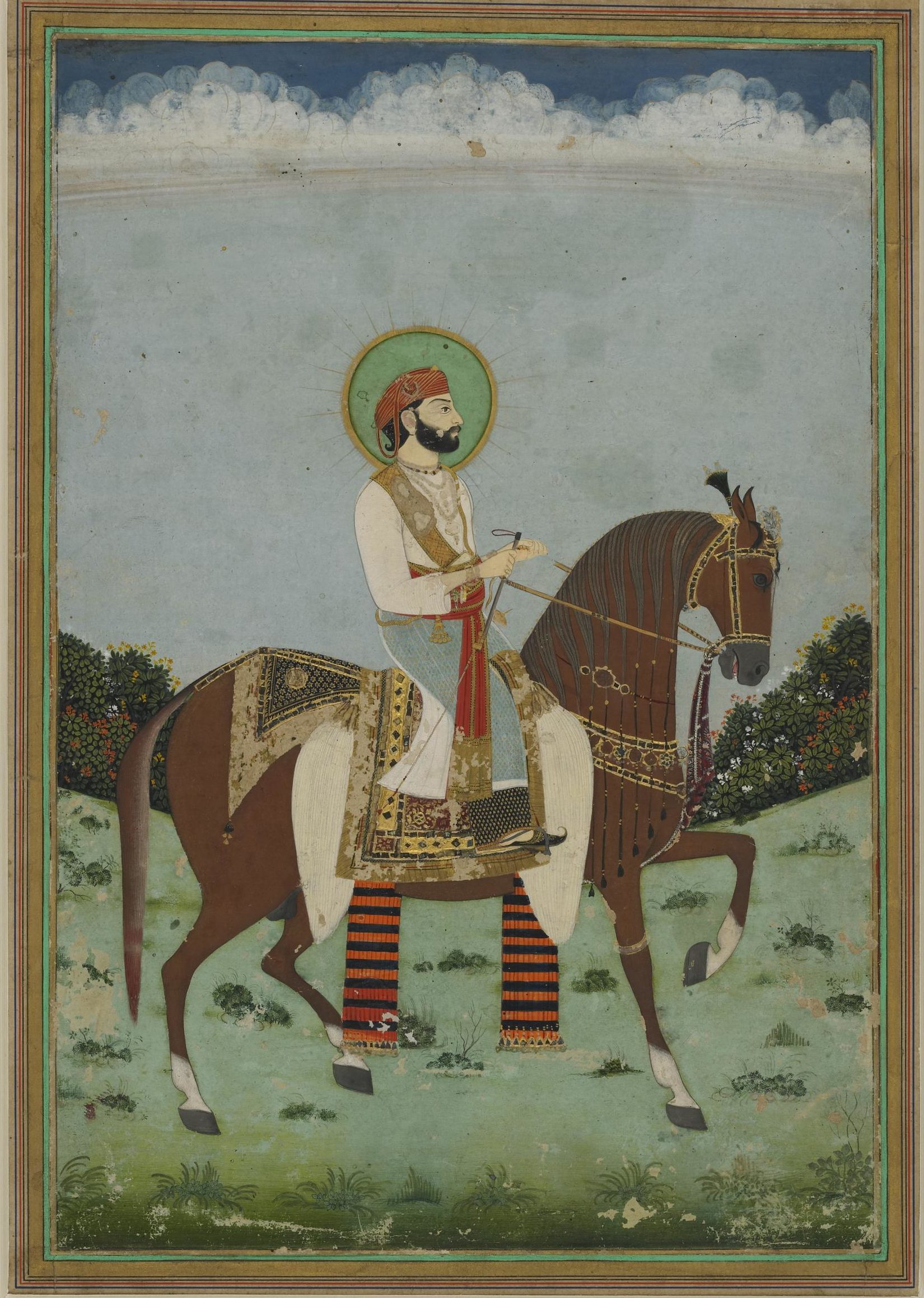

Krishna Choudhary’s ancestors came from Dausa, a town fifty-five kilometres from the capital of Rajasthan. They settled in Jaipur in 1727, twenty years after the reign of the last “Great Emperor” Mughal Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) ended. The patriarch Choudhary Kaushal Singh was initially a financial advisor to Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II (1686-1743), the founder of the city of Jaipur. He was in charge of minting coins and lending money, and also managed a Jagiri (i.e. an estate) of eleven villages around Jaipur. His role was to maintain law and order and to collect revenues and taxes. Choudhary Kaushal Singh soon rose to prominence in the Royal Court of Jaipur.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

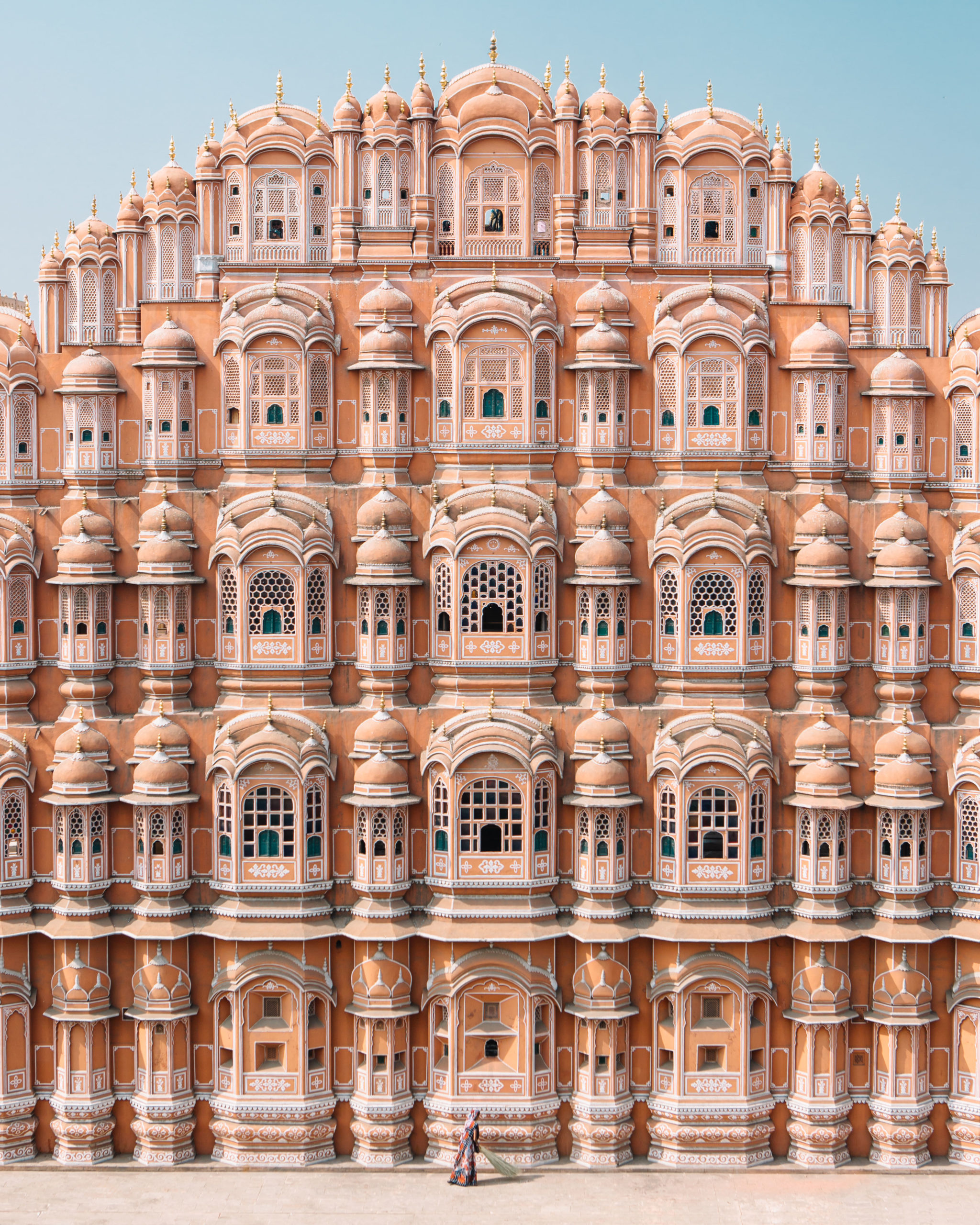

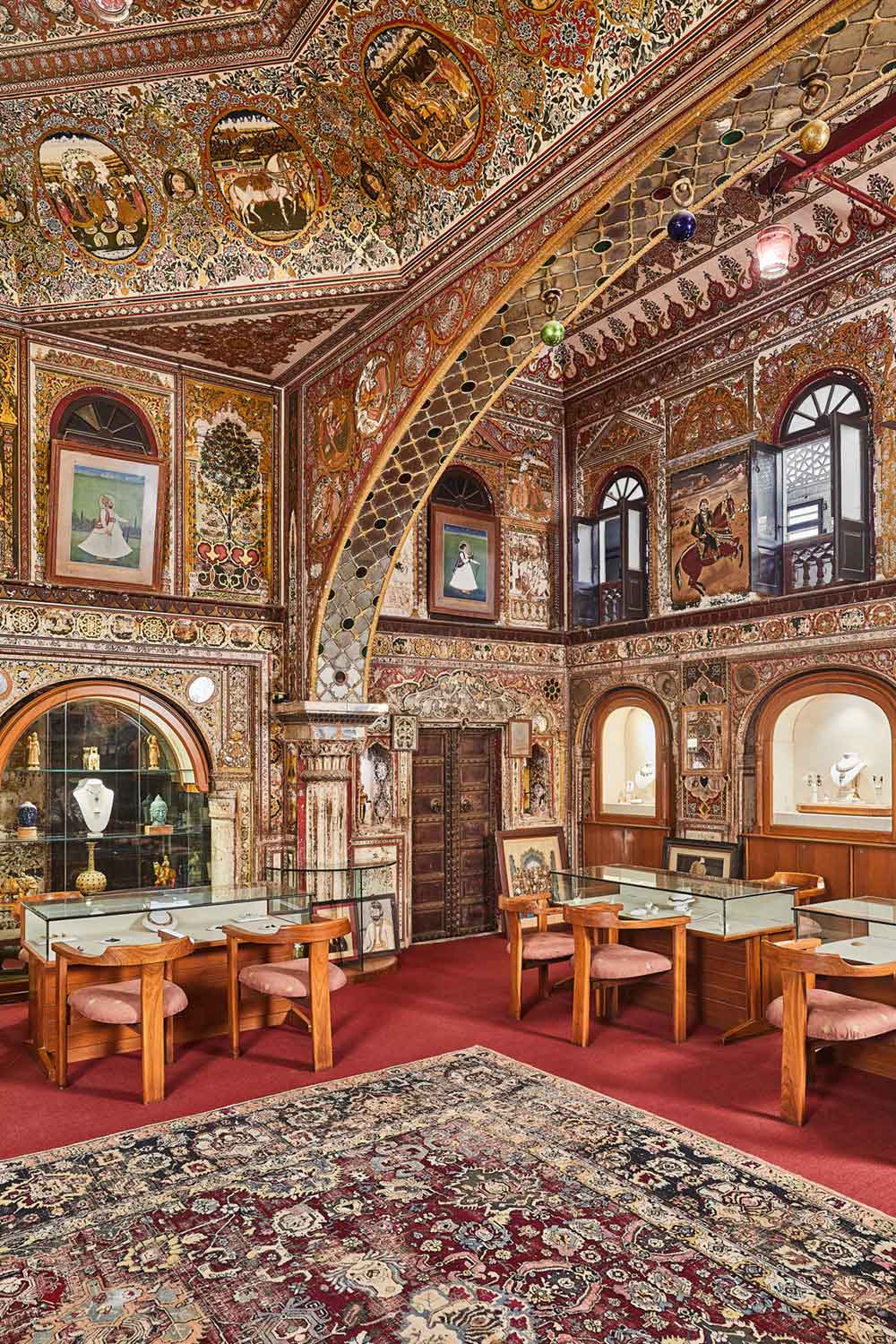

Over the decades, the “Choudharys” became gem dealers and jewellers. “This transition occurred several generations before my grandfather, says Krishna Choudhary, but although we have records going back to 1696, we don't know exactly when”. Initially settled on the site where the Hawa Mahal, the Palace of the Winds, was built in 1799, the Choudharys then lived for a time opposite this Palace before settling permanently in the early 19th century in what is still today their family haveli “Saras Sadan”. This haveli houses the family business, Royal Gems & Arts. It is a unique place where the walls are entirely decorated with colourful frescoes from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Plants and garlands of flowers, rosettes and geometric patterns, draperies and gilding stand alongside the legends of ancient India - an innumerable pantheon of gods, Maharajas, Hindu princesses, horsemen and scattered clouds of birds. For the visitor, and I was lucky to be one, it is tempting to stay for hours in this wonderful atmosphere; fortunately for the master of the place, Santi Choudhary, the brilliance of the jewels and precious objects displayed in the wooden niches of the walls quickly attracts the visitor's eye!

Jaipur, over three centuries of jewellery tradition

The link between Jaipur and jewellers dates back to the early 18th century, when the city was founded by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. He was a central figure in the Mughal dynasty, although he was a Hindu. At the head of his armies, he supported Emperor Aurangzeb, then his successors, and in return enjoyed imperial protection. Having become privileged and powerful thanks to this alliance, Sawai Jai Singh II brought to his court renowned artisans, including jewellers, who all participated in the development of the city and dissemination of the arts.

Three centuries later, Jaipur is a major centre for international jewellery. Professionals go there to cut and trade coloured stones. For example, three quarters of the world's emeralds are cut by lapidaries in Jaipur! “Diamond cutting, which requires a different kind of expertise, is mainly done in the city of Surat, and its trade in Mumbai” says Krishna Choudhary.

It is also in the Pink City that 90% of Indian kundan settings are made. This setting technique appeared during the reign of Emperor Jahangir (r.1605-1627), an important aesthete and patron of the arts whom Krishna Choudhary greatly admires. The kundan consists in surrounding a gem with a thin sheet of pure gold to fix it well in its support. The manipulation is done at room temperature and the setting is done by molecular bonding. This technique of inlaying gems, still in use today, allows the jeweller to work on any type of surface (gold, rock crystal, jade) and to set stones of various shapes.

Another typical art of Jaipur is that of enamelling, even if it tends to be “not as good as it used to be”, regrets Krishna. Red, blue, green and white are the signature colours of Jaipur enamel.

Finally, the capital of Rajasthan is also renowned for its jewellery. Designers come here from all over the world to buy or have their jewellery made; as for tourists, it is “at the Johri Bazaar that they can buy gold or silver jewellery, while the Bapu Bazaar is more devoted to costume jewellery” explains Krishna Choudhary.

The Pink City, a favourite place for jewellery professionals and enthusiasts, is part of a larger and even older history of jewellery in India.

A glimpse into an age-old art: jewellery in India

Hindu beliefs about precious stones

There are many texts on the importance of coloured stones and diamonds in Vedic literature. “Each stone, explains Krishna Choudhary, has particular spiritual and cosmological significance and is classified according to a hierarchy of value”. Thus, the five most important gems are grouped under the name Maharatna (ruby, diamond, emerald, sapphire and pearl) and the next four under the name Upratna (coral, garnet, cat's eye and yellow sapphire). The gem par excellence for Hindus is the ruby, Ratnaraj, which is associated with the sun.

“In the Hindu culture of ancient India, says Krishna Choudhary, the most beautiful stones and jewels were offered to the temples. The king came second”. However, all Hindus adorn themselves with jewellery, more or less richly, depending on their place in the hierarchy of the caste system. This is often shown in ancient Hindus statues.

@The MET Fifth Avenue

Some typical characteristics of Hindu jewellery

Hindu jewellery is traditionally mounted on yellow gold. It is brightly coloured by precious or semi-precious stones cut in cabochon, pear, shuttle-cut or presented in the form of pearls. The main colours that come to mind when thinking about this jewellery are green (emerald, enamel), red or pink (ruby, spinel, tourmaline) and white (pearls, enamel). Necklaces, bracelets and head ornaments are studded with flat diamonds, simply polished, as jewellers continue the age-old tradition of keeping as much weight as possible on the gem compared to the rough. Cultural references appear in the designs, such as the sun, certain flowers (lotus, water lilies, orchids or jasmines) or the makara, the mythological creature with multiple symbols - half terrestrial-half aquatic - and which can be recognised by its attributes: a trunk on the top of the head, a gaping mouth and the tail of a fish or marine animal at the end of the body. “This type of jewellery, says Krishna Choudhary, is very popular in India, and can be found in all the workshops in the country, with some variations depending on the state”.

According to Krishna Choudhary, the essence of Indian jewellery could be defined by this aphorism: “More is more”. In contrast, the jewellery pieces he has been creating since 2019 are characterised by “Less is more”. More than the Hindu tradition, his sensibility leads him to Indo-Mughal art, influenced by Persian culture and Islamic Arts.

The Mughal contribution to Indian aesthetics

“In the arts of Islam, the representation of the living is banned from the spiritual or sacred domain but not from the private or profane domain”, says Krishna Choudhary. Thus we find scenes of daily life (court ceremonies, hunting, romantic or warlike scenes) as well as an important animal and plant iconography on buildings, in interiors, on textiles, tapestries, ceramics, illustrated manuscripts and in jewellery.

From the time of their arrival in India in the 16th century, the Mughal emperors developed plant and floral motifs extensively in their arts. There are two main reasons for this, explains Krishna Choudhary: “The first is the nostalgia of these emperors for the gardens of the East, Babur and the gardens of Samarkand, Humayun and the Persian gardens, Shah Jahan and the gardens of Shalimar etc... The second reason lies in the symbolism of the garden which in Islam represents paradise, peace and divine grace”.

Some characteristics of Mughal jewellery

In Islamic art, there is a metaphorical language of colours. Applied to jewellery, the red of spinels imported from Badakshan (a mountainous region bordering Afghanistan and Tajikistan) expressed power and royalty. Emperors liked to wear long necklaces around their necks with spinels in the form of large oblong pearls combined with sumptuous emeralds imported from Colombia, and large pearls. The deep green of the emeralds was imbued with spiritual virtues and recalled the prophet's favourite colour. As for the fine pearls, fished in the Persian Gulf, they symbolised purity and were the most commonly worn gems of the Mughal emperors. Krishna Choudhary sees a practical reason for the abundant use of fine pearls in Mughal jewellery: they were simply easy to wear and fitted perfectly into the Mughal's flowing, loose-fitting clothes.

The most beautiful gems were sometimes engraved and became the central element of the jewellery. Spinels were engraved with royal titles, emeralds, protective amulets, calligraphed with verses from the Koran and/or decorated on their other side with floral motifs. Flowers and plants were represented in a naturalistic figurative style but were sometimes idealised, particularly in the designs of “celestial flowers”. The floral species of the Mughals differed from those favoured by the Hindus, notes Krishna Choudhary. The rose was a particularly beloved motif, and the Emperor Jahangir and his Persian wife Nur Jahan were devotees and encouraged its cultivation. But there were also tulips, poppies, carnations, irises, daffodils, lilies etc...

Some rare diamonds were also engraved. For example, the Shah rough diamond in the Kremlin Diamond Fund collections is engraved with the names of three of its owners: Nizam Shah (1591), the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (1641) and Fath Ali Shah (1826).

Setting technique most closely associated with Mughal jewellery is kundan, mentioned above.

Jewellery making in India (from the north of the subcontinent to the Deccan plateau) underwent a profound evolution during the Mughal period. The craftsmen of the royal workshops skilfully combined the best of the Indian jewellery tradition with Persian influences and a style was born. This style, which embraced the jewellery arts, endured despite the decline and fall of the Mughal Empire. When India came under British control in 1858, the Mughal style gradually extended its influence on Western aesthetics.

The 20th century: jewellery influences shared between India and the West?

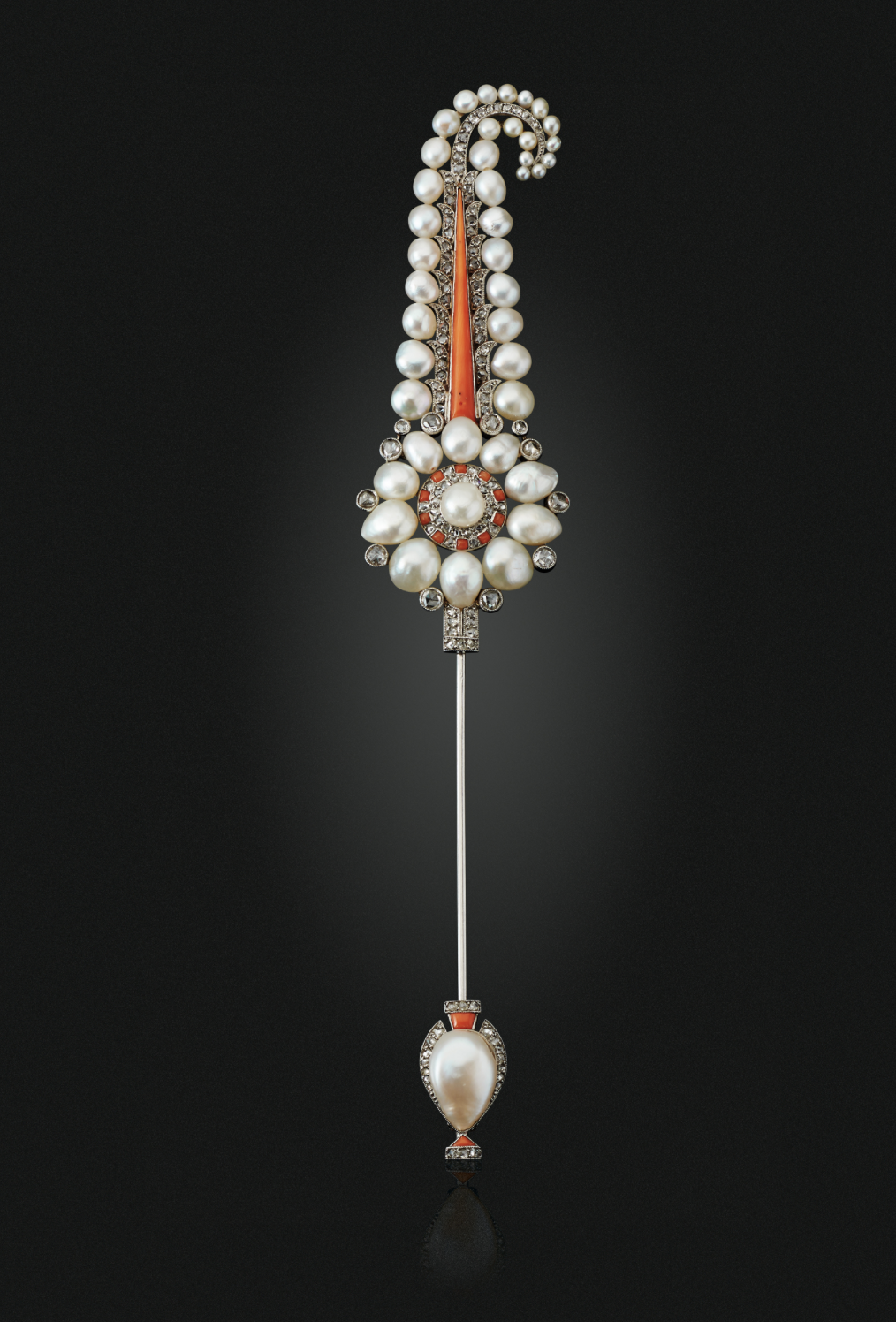

Indian aesthetics and Mughal jewellery strongly inspired the great European jewellery houses, which reinterpreted the combinations of gems, the shimmering mix of colours, the shapes - in particular the paisley motif in the shape of a teardrop with a curved upper end - and the use of engraved stones. The major jewellery houses of the first half of the 20th century, however, resisted the use of yellow gold because platinum was in vogue. Jewellery literature abounds with extravagant stories of Maharajas from the richest princely states in India coming to London and Paris to have entire chests of precious stones set in platinum. Conversely, the influence of European jewellery in India is rarely discussed.

Krishna Choudhary recalls that under the British Raj, jewellery workshops were created in Calcutta for Europeans who came to live or visit India. Jewellery inspired by what was done in Victorian London (1837-1901) appeared between the 1860s and 1880s. This influence of European design can be seen in the shape of several late 19th century rings from the Nizam collection in Hyderabad (see Jewels of the Nizam, Usha R Bala Krishnan, p.221-223). In contrast, yellow gold remained the precious metal of choice for Indian jewellers for decades to come. Since the 1980s, a new breed of jewellers, including Krishna Choudhary, has been breaking away from it.

It is astonishing to note that since the conquest of the Great Mughals, no new foreign influence has imposed itself on India; Westerners played an important but indirect role during the last third of the 20th century.

Independence, end of privileges and abolition of the privy purse: Indian jewellery in danger

The year 1947 was marked by the dissolution of the British Empire followed immediately by India's Independence on 15 August. At the time of Independence, there were 555 princely states covering almost half of India's territory and about one-third of its population. Under the Indian Independence Act and the incorporation of the various princely states into India or Pakistan, the various rulers (Maharaja, raja, Nizam...) were forced to give up their power in exchange for “privy purse” (a tax-free private grant of about a quarter of what they had previously earned).

Twenty years later, in 1971, Indira Gandhi (1917-1984) abolished the privy purse. Until then, these rulers had been the main sponsors of jewellery in India: their relative impoverishment was not without consequences for the Indian jewellery market.

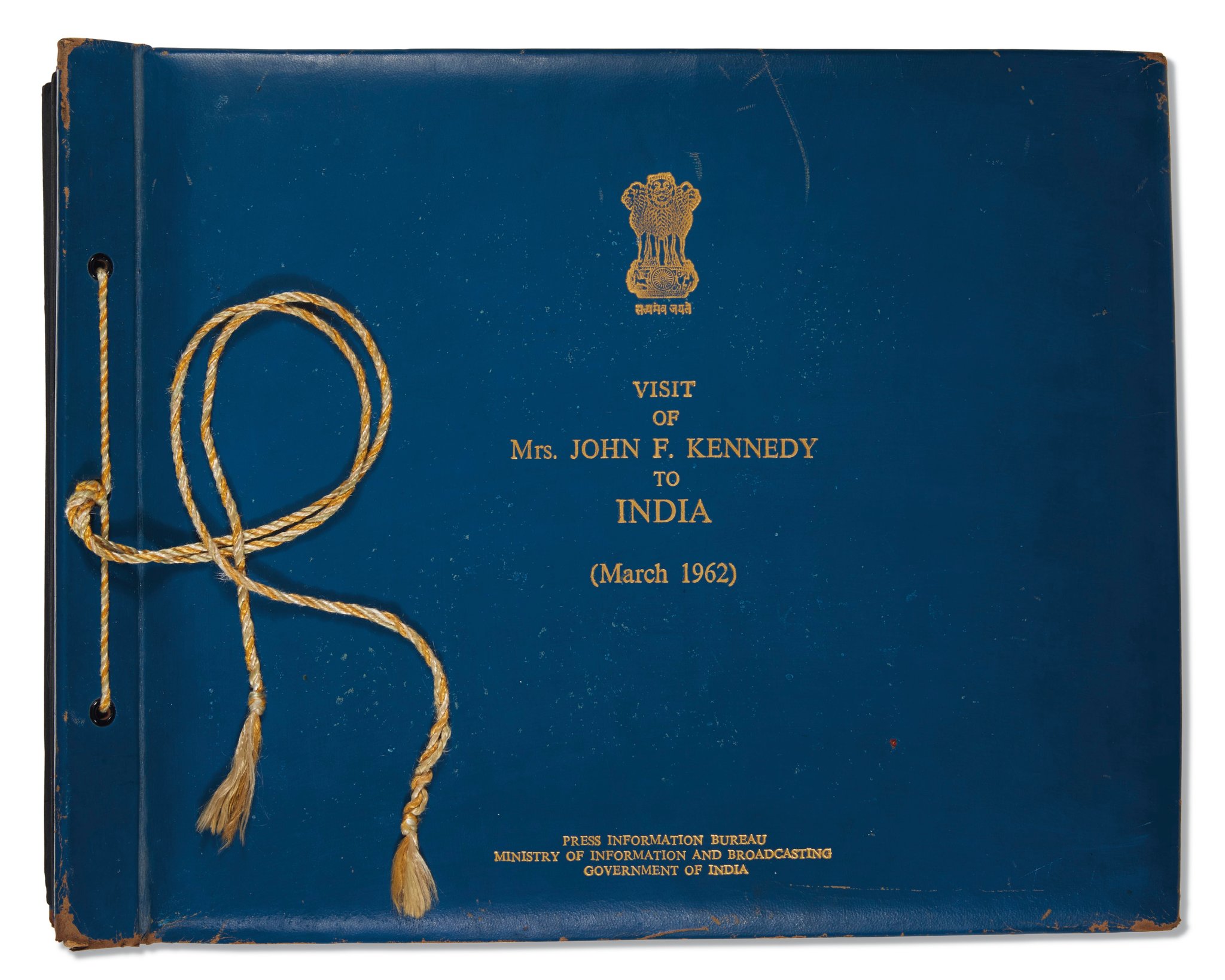

Krishna Choudhary believes that the Indian jewellery industry was able to survive after independence thanks to foreigners. Many Western jewellers, following in the footsteps of Jacques Cartier, came to India to buy gems and engraved stones, not hesitating to acquire, when possible, elements of princely finery from penniless sovereigns. Media personalities such as Jackie Kennedy and her sister Lee Radziwill contributed to the watered-down, romantic image of India, while discerning collectors such as Sheikh Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah and Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah of Kuwait came in 1975 to acquire the first pieces of their extraordinary collection of Islamic art.

“It was in the 1960s, under the leadership of my father Santi Choudhary, adds Krishna Choudhary, that our family business was renamed “Royal Gems & Arts” in order to open it up more to international trade”. Until then, trade was conducted on the floor on large Persian carpets, as seen in the photographs of Jacques Cartier's trip to India in the 1920s and 1930s. Santi Choudhary began travelling to Europe in the 1970s to organise exclusive exhibitions of his creations. Today, Royal Gems & Arts has become an institution whose name regularly appears on the list of art exhibition lenders around the world.

Khrishna Choudhary & Santi Jewels

Krishna Choudhary is undoubtedly an heir to this long jewellery tradition. This legacy he received at birth is of immense wealth; it is also heavy with responsibility. Krishna Choudhary is aware of this. His extreme courtesy, great culture and deep modesty testify to this at each of our meetings. Krishna admits his humility in front of the treasures at his disposal. He works essentially with gems drawn from a family treasure accumulated over three centuries. The gems he uses most are the Maharatna: diamond, emerald, sapphire, pearl - but he readily replaces the ruby with spinel, the gem most associated with the Mughal Emperors.

In this spirit, Krishna Choudhary has created a pendant composed of six flat spinels of heptagonal shape coming from the same mine, of which only one, placed at the top of the motif, has been slightly re-cut. (It should be noted that Krishna Choudhary, out of respect for the historical stones for which he creates new settings, tries as much as possible to keep them in their original size. If re-cutting is necessary, it is then entrusted to the hands of the best workshops in Jaipur). The spinels of a delicate pink and perfect purity, held by four fine yellow gold claws, form the petals of a stylised flower, the heart of which is a square old-cut diamond set on brilliants. A heavy diamond dewdrop drips from the flower. The jewel rests on a black silk cord in the pure Indian tradition. A double leaf on each side of the cord, or perhaps four paisleys, rests on the collarbones. The clasp repeats the same motif, but with lines of diamonds encircling a final spinel, this one octagonal. A true testament to the flat stone in India, this jewel celebrates India's heritage in a very contemporary style.

Krishna Choudhary likes to work with abstract, geometric figures. He has a predilection for herringbone patterns that combine geometry with movement and refer indirectly to the vast water features (pools, fountains, canals) that refreshed Mughal gardens. Two pairs of earrings of a completely different style, one in gold and diamonds cut in the shape of a paisley, the other in titanium and diamonds, symbolise this movement of water in the form of graphic chevrons.

When asked about the symbolism of the gems, Krishna Choudhary says that he does not attribute talismanic properties to the stones he works with: “I use them because I like them, because they have a history. I can be inspired by their ancient charm, but I do not rely on astrology or religion”. A proof of this is his passion for sapphires - a gem perceived by Hindus as potentially a bad omen because it is associated with Saturn. Santi Choudhary has in his private collection a magnificent Mughal-era cabochon star sapphire that is so large that it cannot be closed with the fingers. He called this exceptional sapphire "Krishna".

Courtesy Royal Gems Jaipur. Photo Ashish Sahi

Santi Choudhary, Jaïpur, the Mughal Emperors and India are the primary influences that nourished Krishna Choudhary, but did he have other less direct natural influences? Krishna answers immediately “The Cartier brothers because they took the quintessence of Indian jewellery and magnified it. I see a distant parallel with Mughal jewellery, which also drew on the best of different traditions to create a unique style”. JAR's unconventional designs gave Krishna the courage to dare new materials such as titanium; Suzanne Belperron (1900-1983) and her French style, and Ambaji Venkatesh Shinde (1917-2003) who made sumptuous baguette diamond necklaces for Harry Winston, are also a source of admiration for the jeweller.

Santi Jewels is aimed at connoisseurs who enjoy the dialogue between the ancient and the modern that Krishna Choudhary subtly allows in the six to seven pieces he designs each year. In a time that sometimes gives in to the conveniences of mass production, this respect for tradition, this rootedness, this ability to make the contemporary resonate with the heritage are of great cultural and aesthetic value, making each piece an event in itself.

***

Santi jewels, by appointment only

Royal Gems and Arts

3768, Saras Sadan, Gangori Bazar

Jaipur, Rajasthan 302001, India

Victoria and Albert museum

Cromwell Rd, London SW7 2RL

***

Update September 19, 2022

Selling Exhibition Jewels by Santi

20 – 23 September 2022

Phillips London

30 Berkeley Square. London W1J 6EX

Phillips presents Jewels by Santi, a selling exhibition of the exceptional new creations by designer Krishna Choudhary together with many of the historical Mughal jewels and objects that inspired them.

Thomas Faerber (I) : A life for jewelry

Renowned jeweler specializing in precious stones, antique and vintage jewelry and exceptional pieces, Thomas Faerber, has been acknowledged for more than five decades for his contribution in the jewelry market throughout the world.

The “Faerber-Collection”, placed under the aegis of Thomas Faerber, Alberto Corticelli (at his side since 1988), his children Ida Faerber and Max Faerber, and Philippe Atamian (all three joined the company in 1998), buy and sells gems, antique and vintage jewelry, exceptional pieces in Europe (Geneva and Paris), America (New York) and Asia (Hong Kong). The House stands out, says Thomas Faerber, by a taste for "the emblematic jewels of an era; those of noble origin, created by the most remarkable craftsmen; pieces that, if they could speak, would tell a thousand stories. "

Thomas Faerber belongs to the exclusive club of major international collectors.

Given to a French nobleman as a present from Czar of Russia, Alexander 1st , in Erfurt.

The square step-cut emerald framed by a closed back yellow gold leaf and flower motif set with rose-cut diamonds, surrounded by 16 old mine-cut diamonds and a second line of rose-cut diamonds. The mounting is in silver and 14k gold, typical in the Russian work at the time. The emerald weighs 5.84 carat and is of Colombian origin. The 16 diamonds weigh circa 5.50 carat. The ring is in the original fitted box.

Length : 32mm. Width : 20mm. Height : 24mm. Size : 14 / 54.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

It is a great honor for me and I am grateful to him for having opened these rarely seen pages of this private collection catalog, giving me the opportunity of presenting these masterpieces that he is particularly fond of and willing to lend to jewelry exhibitions as well as to the readers of Property of a Lady.

The collection is an amazingly eclectic set and includes pieces from the Renaissance to 2019. It mainly brings together pieces that were “love at first sight” and at times memories, explains Thomas Faerber. Just like this Belle Époque pearl necklace which was made by Thomas Faerber's maternal grandfather at the beginning of the last century.

The five-strand necklace set with cream-colored natural pearls, ranging between circa 3.0 and 3.5 mm, decorated with four campanula-shaped spacers, delicately millegrain-set with rose- and old-mine cut diamonds, mounted in platinum, with original burgundy fitted case signed Aug. C. Schöning, Cologne, Germany, circa 1910, length circa 38 cm.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

Let's discover parts of the collection and gain a better insight of the history of Thomas Faerber.

From the very beginnings to international recognition

August Schöning, the maternal grandfather of Thomas Faerber, was a jeweler and a goldsmith in central Cologne, Germany, between the Belle Époque and WWII. He died in the Fifties. “This necklace is the only piece I own from my grandfather,” explains Thomas Faerber. It was cheer luck that made it possible at an auction in 2019 in Cologne. "I had gone there for another piece that interested me and then came across this necklace. It was one of the most exciting auction in my life because I absolutely wanted to get it! "

Thomas Faerber's father, Ernst Faerber, came from Bavaria. He was born at the turn of the century, in 1900. He was dreaming of becoming a photographer and wanted to take part of the creative development that this technique was experiencing in those years. However, in the sadly difficult context of the end of the Twenties, he couldn't find a job fulfilling his dream and finally had no other choice than to become an intern for a pearl merchant in Berlin. He lost no time and learned the various technics of coating, piercing and bead threading.

Thomas Faerber explained to me that a man in 1930 came forward to sell a very beautiful necklace of fine pearls. “My father asked the pearl merchant, his boss, if they could purchase it and he refused. He then asked for permission to buy it himself and he also asked if he could obtain a raise to no avail. This gave him no other choice than to set up his own business and buy the necklace." Ernst Faerber worked several weeks on the necklace, peeling it meticulously and turning it into a stunning piece it is today.

Having become a recognized trader in fine pearls and precious stones, he began to travel through Germany. One day, on his way to Cologne to see his client August Schöning, Ernst Faerber came across a thief running away from the jeweler's store and the jeweler chasing after him with a gun. Ernst Faerber did the only thing his heart told him to do and rushed to the jeweler's daughter in distress.

"My story began with love and a piece of candy"

The first thing Ernst Faerber did was to offer the young woman a piece of candy, as he always had some in his pockets -and "this is how my parents met! "

Ernst Faerber, married Maria Schöning (August's daughter) in the early 1930s. Ernst Faerber worked until he died in 1961. "I was barely 17", says Thomas Faerber. The Ernst Färber House, located on the elegant Promenadeplatz in Munich, was taken over by Rudolf Biehler, his former assistant after Ernst Faerber's death. Dominik Biehler is now in charge of the House Ernst Färber in Munich.

"It was agreed by the family that I would be trained by Rudolf Biehler so that at the age of twenty-five I would have an equal 50% partnership with him. I then went to Amsterdam where I learned to cut diamonds and then to Antwerp where I learned to negotiate them, notably at Backes & Strauss.

Thomas Faerber continued his training in London at Australian pearl company and after in Paris with Jean Rosenthal (1906-1993), a great dealer in precious stones, whom he affectionately nicknames "his great master". These months spent at his side are described as "wonderful". Today, it is with his son, Hubert Rosenthal, that he continues to maintain an indestructible friendship.

In 1968, Thomas Faerber decided to create his own trading company in precious stones and jewelry in Zurich, Switzerland, thus leaving the German market to Rudolf Biehler: “The markets were not then as globalized as they are nowadays, everyone had his own territory ". He recalls that when he started traveling in Switzerland, working around with modest jewelers and the few watch factories that existed at this time, was quite "difficult".

Composed of 22 oval enamel plaques each depicting the arms of a Canton within a varicolored gold openwork filigree mount set with spaced close-set pink topaz and with a collet set small cabochon turquoise between each mount. With a pendant drop suspended in the center depicting the symbols of the Confederation.

"Swiss enamel was a very popular souvenir for tourists visiting Switzerland in the 19th century, especially for the British. Geneva was the center for enameling. This Necklace depicting the 22 Cantons of Switzerland is a typical souvenir of that time" explains Thomas Faerber. Photo credit Katharina Faerber

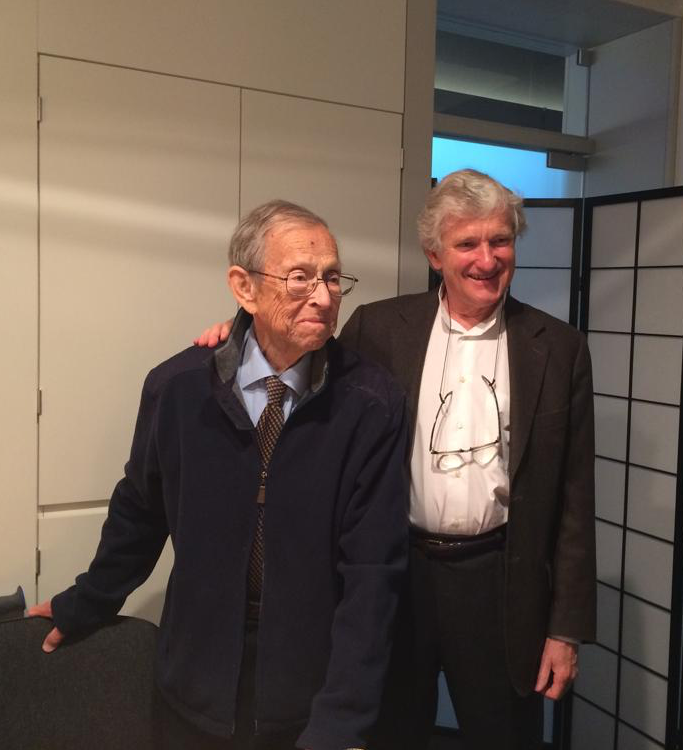

The year 1969 was an important turning point in the life of Thomas Faerber. That summer he visited New York for the first time and made two momentous encounters there. First Katharina, a photographer, who would become his wife and then Paul Fisher (1927-2019), a major player in the jewelry industry of the second half of the 20th century, whom his peers regard as a model. Thomas Faerber fondly remembers a man whom he considers a second father. “He guided me a lot. We have worked together in America and all over the world”.

Another major year in Thomas Faerber's professional life was 1973. He took his first booth, precisely 9m2, in Basel, the jewelry and watchmaking fair that had not yet become Baselworld. Exhibiting mainly for the Swiss market, Thomas Faerber remembers that his activity was mostly devoted to diamonds, with stones rarely exceeding 1 carat. In order to develop his entreprise, Paul Fisher suggested that Thomas Faerber present antique jewelry as well. In Switzerland at that time customers wanted modern jewelry he explains : “My reputation was just starting to establish itself, so I was hesitant, but not for long. I was the first jeweler and gems dealer to exhibit antique jewelry. At the end of the fair, the three antique jewels that Paul Fisher had given me were sold and this allowed me to meet new customers ". Thomas Faerber never left the antique jewelry market again and remained an exhibitor Basel until 2017.

The wristwatch designed as two enlaced snakes, decorated with black, green, red and blue colored enamel, the heads embellished with a collet-set garnet- cabochon, to the gem-set eyes, the snakes centering upon the round-shaped case with guilloché enamel reminiscent of a rose glass window, opening to reveal roman numerals, numbered ‘46373’, mounted in 18k yellow gold, probably English, circa 1840, inner circumference circa 19 cm, with winding key.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

In 1980, Thomas Faerber moved to Geneva, a city with a prosperous jewelry and watchmaking tradition, while continuing to travel. America in the late 1970s was a haven for discerning dealers coming from all over the world as the dollar began to fluctuate. "I bought some beautiful vintage signed jewelry there: at the time, between a Cartier bracelet and an unsigned Art Deco bracelet there was 15% to 30% difference. It was later, from the 1980s, that signatures and origins became much more important. The fact that jewelry began to be exhibited in museums (e.g. Van Cleef & Arpels exhibition in 1992 at the Fashion and Costume Museum at the Palais Galliera in Paris) has contributed in changing mentalities as well as the international jewelry market."

Over the years, thanks to his in-depth knowledge and business ethics, Thomas Faerber has been able to establish a notoriety (from 1993 to 1998 he chaired the Swiss Precious Stones Dealers Association) as he never stopped acquiring new important pieces.

In 2004, he provided the Louvre with a necklace of emeralds and diamonds and matching earrings that Napoleon I presented to the Archduchess Marie-Louise on the occasion of their wedding in 1810. Thomas Faerber explains that after acquiring these two exceptional pieces, miraculously preserved in their original state, he very much wanted them to be part of the fabulous Louvre collection. This half-set created by François-Regnault Nitot was part of the Empress Marie-Louise's personal jewelry items and has since entered the window display of the admirable Diamonds of the Crown of France located in the splendid Galerie Apollon.

That same year, Thomas Faerber was made a Chevalier of the "Ordre des Arts et Lettres".

Pieces made by the jeweler François-Regnault Nitot (1779 - 1853) in Paris. The necklace consists of 32 emeralds (13.75 ct central emerald); 1138 diamonds (874 brilliants and 264 roses); gold ; money. The earrings are made of 6 emeralds; 108 diamonds; gold ; money.

Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (Louvre museum): Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Thanks to many years of experience and a large international network, Thomas Faerber and his colleague Ronny Totah joined forces four years ago to create "with colleagues, friends and other dealers, a quality, friendly and family-like jewelry fair on a human scale”: GemGenève.

The first two exhibitions, which brought together jewelers, dealers, designers, collectors, gemological laboratories, booksellers and enthusiasts, took place in 2018 and 2019 successfully bringing together exhibitors and visitors from all over the world.

Hopefully GemGenève will reopen its doors in November 2021.

This conversation with Thomas Faerber will continue here : "About the collection"

***

Visual at the top of the article: An antique sapphire and diamond bangle mid 18th century.

The brooch element set with a sapphire of circa 56 carats, within an old mine cut diamond surround dated from the time of Catherine the Great (mid-18th century). According to family tradition, this jewel belonged to the Zoubov family.Possibly a gift by the Empress Catherine the Great to Platon Alexandrovitch Zoubov (1767-1822) who was the Empress' last favorite.

The yellow gold bangle, a later addition, has the St. Petersburg mark used from 1826 up until 1876 and master’s mark, Cyrillic script P I. It is encrusted with small ivy diamond motif of pre-art nouveau style. With report no. 47838 from the SSEF stating that the sapphire is from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) with no indications of heating.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

***

Many thanks to Myriam de Mareuil for her very careful proofreading of my translation

Thomas Faerber (II) : A conversation about the Collection

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquer ici

“The collection is eclectic,” says Thomas Faerber. I purchase what I like. It can be antique, modern or contemporary ”.

Designed as a flexible torque, composed of brushed gold links on a black rubber band, mounted in 18k yellow gold, with Austrian assay marks, with Manfred Seitner maker's mark, circa 1970, inner circumference circa 50cm, width circa 3.2 cm.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

Jewelry, watches and precious objects make up for this collection, which began in the 1970s with “a few pieces of lesser importance”. Over time and through the various fairs, Thomas Faerber regretted having sold certain pieces. "This, I believe, is how the collection started." He adds that even today, most of the pieces that he and his associates buy are intended to be sold: "I remain a dealer at heart. "

Do you plan to exhibit your collection one day?

I prefer to lend parts of it.

With report no. 63234 dated 26/04/12 from SSEF stating that the sapphire is from Ceylon with no indications of heating.

With a certificate of authenticity by Chaumet.

The original drawing of this piece is kept in the archives of Chaumet.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

The great Houses of Place Vendôme and the museums are mostly aware of this and don't hesitate if needed to ask me. Some of you may have already admired this brooch during the "Chaumet en Majesté" exhibition at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco in the summer of 2019? It was also featured at the Beijing exhibition.

"Plume" brooch by Morel & Cie, J. Chaumet.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

At the beginning of September, Thomas Faerber left an exceptional necklace in emerald drops and diamonds designed by Jacques Arpels in 1950, as well as a pair of matching earrings, on loan for the Pierres Précieuses exhibition at the Museum of Natural History (MNHN) in Paris.

This set belonged to Maharani Sita Devi of Baroda (1917-1989), wife of Maharaja Pratapsingh Gaekwar.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

Sita Devi had an unrestrained passion for jewelry and possessed extraordinary gems which she drew from the Baroda treasury. Some of these precious stones date back to Mughal times. In the latter part of her life, the Maharani saw her jewelry dispersed during an auction organized by Crédit Mobilier de Monaco on November 16, 1974. The emerald and diamond half-set created by Jacques Arpels was part of a private collection before Thomas Faerber acquired it at an auction in May 2002.

Almost twenty years later, the collector continues to admire the design and the gems of this magnificent set that he considers exceptional.

Do you have a favorite jeweler?

I have great admiration for the work of Lalique, Vever, Cartier and, today for JAR - but one of my great heroes is Frédéric Boucheron (1830-1902)!

The tremendous quality of the execution of the pieces created under his direction, the human value of the character, his sensitivity, the fact that he was so involved in the profession and that he was keen to help younger generations aroused my admiration.

That is why the first major acquisition in my collection was a Boucheron necklace.

Composed of 900 diamonds for a total weight of circa 45.75 carats, this necklace is the only surviving piece to be known according to the technique invented by Frederic Boucheron in the end of the years 1890. The necklace is composed of a very thin flexible steel thread covered in silver. It can be transformed into a brooch, length : 21 cm, rose width : 3 cm, rose height : 12.5 cm.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

The first drawing of this necklace made by Paul Legrand, main designer of the House of Boucheron at the time of Frédéric Boucheron, dates from 1879. It then took a few years to carry out this project and invent a technique which made it possible to bend and thread the metal around the neck, without the diamonds jumping under the pressure of the movement. Achieving this extraordinary flexibility was an incredible challenge for the workshop. It was only in 1889, during the Universal Exhibition in Paris, that Frédéric Boucheron officially presented his technical innovations, including engraved diamonds and the so-called "Point d'Interrogation" (Question mark) necklaces. The jeweler won the "grand prix" there - the highest distinction after the gold medal - for his remarkable work, and was soon after made an officer of the Legion of Honor.

"Spring collars" (another name for this invention) impressed critics who described them as “revolutionary”! explains Boucheron's Heritage Director, Claire de Truchis-Lauriston. She also draws our attention to how much Frédéric Boucheron was attentive to the comfort of his clients, who at the time had to have a maid to dress and adorn themselves, in particular with their choker (dog collar) so difficult to attach behind the neck. Frédéric Boucheron certainly wanted to free them from constraint. The "Point d'Interrogation" necklaces come without a clasp and most have a central part that can be transformed into a brooch or hair ornament.

Almost all of these necklaces represented nature: flowering branches of acacias, plaine trees, lotus flowers, ears of wheat, peacock feathers, ivy leaves, poppies, snakes… The necklace that Thomas Faerber owns is made up of a blooming rose, surrounded by three leaves, topped with a a rose bud about to bloom.

To this day, this is the only “Point d'Interrogation necklace” in its original state.

“When this necklace was put on sale in Paris in the Eighties at Drouot, says Thomas Faerber, it was estimated at a reasonable price, but during the sale, the bids flew - I had had a formidable opponent in front of me! Nevertheless, I won the bid and this necklace now belongs to my wife. "

Is there a gem that particularly appeals to you?

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

I don't have a favorite stone; nevertheless there is one that has always fascinated me, is the alexandrite, the color change variety of chrysoberyl which has the particularity of changing colors depending on the light (green in daylight, red under a lite candle).

I'm still trying to get chrysoberyls, but their prices are prohibitive. I took a huge risk to get an alexandrite of almost 8 ct put on sale last June in Vienna at the Dorotheum. Estimated between € 13,000 and € 16,000, it was sold for € 115,300. It truly had a very nice color-change. Fortunately, it was another who got it, he said with a smile.

What type of jewelry is particularly sought after by dealers today?

I would say the tiara.

In the 1970s, tiaras were unsaleable, we bought them to take them apart. It reminds me of an anecdote: in the 90s, there was a beautiful tiara for sale at Christie’s. I admit, I had done my calculations to make five brooches, three pairs of earrings ... I won the bid and the tiara was delivered in a beautiful initialed Chaumet case. I thought maybe I wasn't going to take it apart right away, he laughs. I wrote to Madame Béatrice de Plinval, Chaumet's Heritage director, to tell her that I had been able to acquire this tiara. This tiara has since become one of the centerpieces of their Heritage Collection.

Today tiaras are a real craze, e.g. this sale on June 10, 2020 at the Dorotheum, still, a Cartier tiara in aquamarines and diamonds mounted on platinum. Characteristic of the Art Deco style, it was created in London by Jacques Cartier around 1930-35. Estimated between € 34,000 and € 70,000, it sold for € 582,800 (more than seventeen times over its low estimate!).

You also own exceptional objets in the collection. Are there any that you would like to present?

The rectangular case with round corners in 14k yellow gold with a samorodok finish surface, inset with rose-cut diamond, opening on a compartment for the cigarettes, and a smaller case of similar design for the matches, a mirror in the lid, a diamond set push piece, with Russian assay mark for Kiev after 1908 and maker's mark for Josef Marchak, circa 1910, 10.5 x 5.5 cm.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

This rectangular cigarette case with rounded corners depicts a winter landscape around the ghostly face of Ded Moroz, the “Grand Father of Frost” or Russian Father Christmas.

"I don't smoke," says Thomas Faerber, "but the elegance of this set appealed to me."

The cigarette and matching case, both illustrate the technique of samorodok, a Russian word meaning "nugget" or "virgin metal." At the end of the 19th century, this technique was used by Russian silversmiths and in particular by Fabergé who applied it when creating precious objects.

Obtained by heating silver or gold to a temperature near the melting point and then suddenly cooling it in water, the samorodok produces a textured effect on the surface of the object, which suggests snowy forest paths in Switzerland, sand games in the desert, the lunar surface ... Everyone is free to let their imagination run wild!

This technique is nevertheless very difficult to master, the samorodok is rare.

Will you create a Faerber museum in Geneva?

I believe my collection should stay in the family company. I am fortunate to be surrounded by two children and five grandchildren; my daughter Ida Faerber is very attached to our legacy, she'll guard the temple.

***

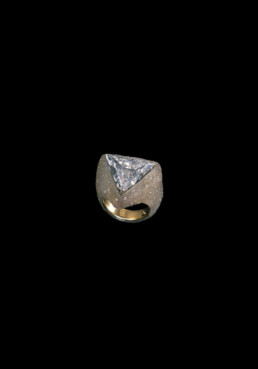

Visual at the top of the article : A Joël Arthur Rosenthal ring that belonged to Marie-Hélène de Rothschild (1927-1996).

Recently acquired at the Pierre Bergé & Associés auction on Tuesday, December 15, 2020, Lot 100. This 18K (750) yellow gold ring is adorned with a troidia-shaped diamond weighing 6.31 carats.The ring is covered with a mosaic of agate geode studded with shards of diamonds. Work from the 1980s. Signed JAR.

Photo credit Katharina Faerber

***

Many thanks to Myriam de Mareuil for her very careful proofreading of my translation

***

Thomas Faerber SA

29, rue du Rhône

1204 Genève

Switzerland

Tel: +41 22 318 66 33

Gourdji

1 rue de Châteaudun

75009 Paris

France

Tel: +33 1 48 78 84 65

gourdji@faerber-collection.com

Faerber Inc.

589 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1103

New York, NY 10017

U.S.A.

Tel: +1 212 752 42 00

ny@faerber-collection.com

Faerber-Collection (HK) Limited

1503 15/F, 9 Queens Rd.

Central – Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Tel: +852 2520 2521

hk@faerber-collection.com

Geneva International Gem & Jewellery Show

Palexpo Genève Halle 7

Route Francois-Peyrot 30

1218 – Le Grand-Saconnex

Genève. Suisse