Books

Celebrate Art this Christmas © Skira Edition

This Christmas, Skira celebrates art in all its forms, dimensions, and colours. From the timeless shots of Vincent Perez to the unparalleled charm of Venice, from futuristic digital art to Impressionism: art is everywhere, and this year we invite you to spread beauty with a Skira gift. Delivery is guaranteed for online orders placed by December 17th. Visit one of our boutiques for exclusive gifts and last-minute Christmas orders.

The Diamonds of Golconda | Les Diamants de Golconde

Golconda was once a region famous for its diamond mines. Today, Golconde gems are among the most sought after by connoisseurs and collectors. Despite the uniqueness of Golconda diamonds, due to their ancient cut, they have never been fully studied, and until now have only been discussed from the perspective of specific pieces or periods. This book fills that editorial gap by providing an in-depth study of the geography, history of the region, gemmology, and mythology built around these diamonds. It also focuses on the region's most famous gems, those in major public and private collections, as well as on pieces that have disappeared.

EAN: 9782370742179

Author: Capucine Juncker

Year of publication: 2024

Number of pages: 208

€50,00

To Property of a Lady readers

Diamonds of Golconda

Readers of Property of a Lady will no doubt have noticed, over the years, the publication on this site of articles on French and European diamonds belonging to royal or princely families, on spectacular auctions of diamonds once owned by American tycoons or film stars, or on Indian jewellery traditions from the 15th century to the present day..

Each of these stories, different in subject and angle, had one thing in common: they all involved Golconda diamonds. And so, article after article, Golconda diamonds gradually appeared to me as a major thread running through the history of jewellery. Not just in the history of India, but in the global history of the jewellery tradition. On closer examination, I realised that this origin had become so legendary that the historical, geographical, social, economic, cultural and even sacred reality of Golconda diamonds had faded behind the myth. A few historical summaries and some fascinating articles on research, sometimes diamond by diamond, existed in English, but they did not necessarily cover the period from the discovery of these diamonds to the present day. The reconstruction of this red thread then became a research project in its own right for me.

This project has now become a book, which SKIRA has agreed to publish, and which is being released in bookshops and on digital platforms soon*. In it, I attempted an approach to the diamonds of Golconda that starts with the geographical and geological origins of the Golconda mines, and then moves on to the Indian part of their history, drawing on both historical accounts and certain literary or religious writings that give them distinction. Contrary to popular belief, diamonds were not always the focus of interest for the rulers of India. Over time, they became a sign of wealth and a symbol of power.

This symbolism was transferred to Europe almost identically. The dominance of Golconda diamonds in royal jewellery is due, of course, to the simple fact that before 1725, Golconda was the only source of diamonds in the world (with the exception of a few deposits in Borneo). But it was also, moreover, due to the fact that the Indian courts, particularly the Mughal, had made diamonds the royal gemstone par excellence, supplanting all others. Queen Victoria would never have been so keen to acquire the Koh-i-Noor if it had not been the very symbol of the power of India, which Great Britain, through the East India Company, was in the process of conquering. But before it, many European sovereigns had coveted diamonds for their economic and political value, perhaps unwittingly replicating the hierarchies established by the rulers of India.

That's why, in this book, after exploring the genealogy of Golconda diamonds, I wanted to trace their international path, from royal courts to American billionaires, from court jewellers to contemporary jewellers who work brilliantly with Golconda diamonds.

Although it has required a great deal of reading, research and travel, this book is not an academic compendium, but a narrative. The diamonds of Golconda can of course be the subject of a thousand and one investigations, but my sole aim was to give readers, interested in the history of jewellery, a first-hand look at the astonishing trajectory of these stones that have become mythical. Born in and around the sultanate of Golconda, their story has often been romantic, sometimes even fantastic. They have become witnesses to a part of our collective history, and have often even played a central role in it.

Through this account and selected iconography, I wanted to invite the reader to engage in a unique jewellery adventure.

Bilingual English/French, hardcover edition, 23 x 30 cm

208 pages, 125 images

ISBN-10: 2370742178 | ISBN-13 978-2-37074-217-9

On Sale : France – 30 October 2024 / 50 €

UK – 28 November 2024 / £ 45

USA – December 31, 2024 / $ 55

Here is the press release

CP_Golconde_EN

Cartier London in the 30's : A decade of contradictions

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Théodule Cartier (1884-1941) recovered and told by his great-granddaughter Francesca Cartier Brickell - PART III

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici

To read part I "He lived for design : Jacques Cartier, the lesser-known brother", click here ;

To read part II "Cartier London: The roaring 20s", click here

What were the 1930s like for Cartier?

My grandfather [Jean-Jacques Cartier] used to tell me how, after the boom of the 1920s, the 1930s brought such terrible challenges for Cartier and other luxury firms, many of whom did not survive. The Great Crash began in October 1929. In just two days, the U.S. equity market lost a quarter of its value, devastating investors, and over the next three years, as the Great Depression took hold, there was wave after wave of banking panic. “Eighty percent of our orders were canceled" Pierre Cartier reported to the American press in 1930. And for those clients that remained, “the Maison had to grant credits varying from six months to a year.”

For Cartier, the difficulty was exacerbated by the sudden decline in demand for the gem that had, for several decades, represented the lion’s shares of their income: pearls. The steady rise in commercially available cultured pearls had put the natural pearl market under increasing pressure since the late 1920s. In 1930, prices for natural pearls plummeted by 85 percent. Cartier suffered considerably as a result: my great-grandfather [Jacques Cartier] said this crashhurt business almost more than the effects of the Depression.

One saving grace during this period was the Cartiers’ – by now well-established – links with India. Not only did the firm continue to receive large commissions from the maharajas at a time when wealthy Americans were reigning in their spending, but also the fashion for Cartier’s Indian-inspired jewellery (including the colourful jewels later referred to as ‘Tutti Frutti’) helped keep the firm ahead of the competition in the West.

New York, 19 June 2019

I recall you writing that the centre of gravity shifted away from Paris to London?

Yes, one thing that’s not widely known is that, by 1925 already, Louis Cartier had stepped down from the Board of Cartier SA in Paris. In the 1930s, Louis was already in his early sixties and effectively retired, spending a significant time away in his Budapest palace (he had married a Hungarian countess) and his Spanish villa in San Sebastian. My grandfather said that Louis used to turn up announced in Paris after weeks or months away and move between the workshops and Rue de la Paix showroom like a ‘meteor’, tearing strips off his team for anything that wasn’t up to his almost impossibly high standards. He’d then disappear again, creating something of a power vacuum in Paris which Louis tried to fill initially by putting his son-in-law Rene Revillon in charge. Unfortunately this only led to more problems, ending in the most unexpected family tragedy, and it really wasn’t until Louis’ brilliant protégé, Louis Devaux, took over in the late 1930s that this power vacuum in Cartier Paris was resolved.

I found it fascinating to read the letters between the brothers which revealed the human behind-the-scenes reality to the flawless impression that the family strove to give the world in their calm beautiful showrooms. Pierre and Jacques, for instance, were worried for the business but they were also concerned for their older brother, admitting to each other (even if they kept it secret from the world) that on occasion they had no idea where he was or when he would be back. Louis still came up with new ideas in this period, and he kept pushing his team to innovate (in one letter asking them to come up with “something tastier, or something new”) but those long absences and the need to be alone were the flipside, perhaps, to his creative genius.

There was also a big argument between Jacques and Louis in the early 1930s. I won’t go into the details here, it’s all in the book, but save to say, relations took a nosedive for a while. In a fit of anger, Louis refused Jacques access to Cartier Paris: “The worst aspect is the sanction taken by LC [Louis] with regard to JC [Jacques]—JC forbidden to enter S.A. locations at 4 or 13 Rue de la Paix. Cessation of all relations between the two companies, no S.A. stock to be sent, ordered, or repaired. Only current business to be conducted, no new business to be carried out.”

Despite this, Cartier London was perhaps the best placed branch in the 1930s as it benefitted not only from the relationship with Indian clients (who Jacques had been visiting for the past two decades), but also the ongoing custom of the British royal court.

These aristocratic clients were not only generally less negatively impacted by the Great Depression than many of Pierre’s clients over the Atlantic, they (and their jewels) also often appeared in the social columns, resulting in the ideal type of marketing for Cartier.

whole-plate glass negative, circa 1909. Given by Bassano & Vandyk Studios, 1974. Photographs Collection © National Portrait Gallery, London

For example, Lady Granard, daughter of the American financier Ogden Mills and wife of the Earl of Granard, had been known in British high society for her love of gems ever since The Washington Post had remarked of her 1909 debut in Parliament that “after the Queen, who wore the crown jewels, no woman in the chamber wore so many splendid gems as the new American countess, and if the Queen had not worn the Cullinan diamonds for the first time, the American countess would have outshone Her Majesty.” Two decades later, though the British capital may have been under the shadow of the Great Depression, court life - and with it the requirement for big jewels - continued. In 1932, Lady Granard commissioned a truly remarkable necklace from Cartier London: it incorporated two thousand diamonds and an enormous rectangular emerald of 143.23 carats (all the gems were her own).

The London branch’s association with the British royal family was bolstered further in 1933 when Queen Mary asked to exchange a gift she had been given from Cartier for a more valuable clip brooch. After Cartier made the exchange for free, the Queen thanked the firm by visiting its New Bond Street store. Looking through the showrooms and the various departments upstairs, “Her Majesty,” Cartier’s director Joseph Sinden recalled, “talked to quite a number of the workmen and the visit lasted an hour and a half.” She had entered through the side entrance on Albemarle Street, but by the time she left, “the news had got round that Her Majesty was here and there were a number of people waiting to watch her leave.”

News of the royal visit was excellent for business. “Bond Street is busy,” Jacques reported a couple of months later; “the workshop is blocked with orders.” Her much-reported visit would also help publicize the fact that although Cartier was a French firm, the London branch employed Englishmen. This was an important message to convey at a time when there was a backlash against firms in London employing foreign workers over British ones.

Later in the 1930s, when Paris was struggling from political and social unrest, London was also busy with 27 tiara commissions for the 1937 coronation. Two years earlier, Vogue declared tiaras had made a comeback in England (“tiaras are all the rage”) and in 1936, Cartier made a diamond and platinum tiara with a cascading scroll design that the future King George VI would buy for his wife, Queen Elizabeth. This piece, known as the Halo tiara, would subsequently be worn by four generations of the royal family, making a special appearance in 2011 when Catherine Middleton (the future Duchess of Cambridge) wore it for her wedding to Prince William. Other significant 1930s royal clients included the future Duke of Windsor, whose purchase of a Cartier emerald engagement ring for Wallis Simpson would effectively lead to his abdication.

A diamond 'halo' tiara formed as a band of 16 graduated scrolls, set with 739 brilliants and 149 baton diamonds, each scroll divided by a graduated brilliant and with a large brilliant at the centre; original red leather box, with later Garrards label. @Royal Collection Trust. All rights reserved

Tell us about Wallis’s engagement ring?

Well, fortunately for Cartier, the Duke of Windsor (then the Prince of Wales) had favoured Boucheron when buying gifts for his previous mistress, Freda Dudley Ward. When he started a relationship with Wallis, he was apparently instructed by her to switch allegiance from one French jeweller to another because she didn’t want anything reminiscent of his previous lover!

The Prince showered Wallis in jewels. A regular to Cartier London, he would generally use the back entrance on Albemarle Street (in order to avoid being spotted by the public) before being discreetly ushered into one of the private client rooms by a waiting salesman. For a high-end jeweller, discretion was the name of the game and for a future king conducting a romantic liason with a married woman, it became particularly important. For most of 1936, the scandalous relationship was successfully kept out of the British press. In fact, Jacques, as one of the King’s trusted jewellers, would have been one of the very few who knew of its significance.

I love the story of the Wallis’ engagement ring. Traditionally, emeralds are not used for engagement rings. Compared to diamonds, the stone is soft and can scratch easily with everyday wear. But King Edward VIII (as he was for a very brief period after his father died and before becoming the Duke of Windsor) wasn’t interested in tradition.

Some years earlier, Jacques had sent a trusted salesman to Baghdad to negotiate the purchase of several important gemstones. On his arrival, the salesman had been informed that the sale had to be conducted secretly and that he was forbidden to telegraph any details back to London. All he was allowed to say was that he needed a large amount of money to be sent over as soon as possible. Trusting his employee, Jacques approved the sum and had it wired over without delay. For such a large price, he supposed, Cartier would be acquiring an enormous number of precious gems. But when his salesman re-turned, he had with him only a small pouch. Out of this, he brought one single gemstone. It was an emerald the size of a bird’s egg. Jacques was enthralled. As a gemstone expert, he marveled at the chance to see and hold one of the great emeralds of the world, a gem so magnificent it had once belonged to the Great Mughal. But as a businessman, he was dismayed. Years ago, before the Russian Revolution, they would have had no problem finding buyers wealthy enough to afford such a gem. But the 1930s was a very different era. The only option for Cartier to make their money back was to cut the emerald in two and re-polish each half into a gleaming new stone. Though it pained Jacques even to consider splitting such a fantastic gemstone, he had to think of the business. One polished half ended up being sold to an American millionaire and the other, at 19.77 carats, became the centerpiece for Wallis’ engagement ring.

As with many of the jewels he bought for Wallis, the King had asked that Cartier engrave it with a personal message. This one read “WE are ours now 27 X 36.” He proposed on October 27, 1936, the same day Wallis was granted her divorce from Ernest Simpson.

So Jacques – and Cartier London – were caught in the midst of this famous episode in history?

Yes, I love how this episode illustrates the importance of a jeweller’s discretion – how a jeweller may be privy to secrets that even families don’t know about each other, in this case, the Royal Family. Jacques was, on the one hand, working on tiaras for the upcoming planned coronation of King Edward VIII while also working on the ring that would lead to his abdication. In the end, the coronation set for the summer of 1937 would still go ahead, but it would be for a different King than the one the world had been expecting, King George VI. Because once Wallis had the ring on her finger, the British Prime Minister told the monarch that the British public would never accept a divorced woman as their queen. “I think I know our people,” he said. “They will tolerate a lot in private life, but they will not stand for this sort of thing in a public personage.” In a series of meetings, he clearly spelled out Edward’s options: either renounce Mrs. Simpson or abdicate. In a poignant radio broadcast from Windsor Castle, the King announced his abdication and left Great Britain bound for France.

From then on, it would be Cartier Paris which would have the lion’s share of the couple’s jewellery commissions (her most well-known pieces would include a multi-gem flamingo brooch, an amethyst and turquoise necklace and the iconic big cat jewels).

In the 1930s, Cartier London was known for necklaces, and for its topaz and aquamarine jewels– why was that?

Rectangular, hexagonal, square and circular-cut aquamarines, circular and baguette-cut diamonds, platinum, may be worn as a necklace or applied to fitting and worn as a tiara, 16 ins., circa 1935, signed Cartier London, numbered. @Christie's Magnificent Jewels, New York, 5 December 2018.

This was a creative and prolific period for Cartier London, especially for big necklaces – although sadly, many of the necklaces have since been broken down and haven’t survived into the modern period. The head of the design studio, Georges Massabieaux, worked with designers like George Charity and Frederick Mew (Mew was responsible for many of the firm’s more innovative geometric designs). In 1935, the London team was joined by the talented artist Pierre Lemarchand, who moved over temporarily from Cartier Paris. He got along particularly well with Mew, both great admirers of each other’s work, and he would go on to design many of Cartier’s animal jewels during and after WW2 (he was the man behind the famous “bird in a cage” brooch during the occupation of Paris and the panther jewels for the Duchess of Windsor).

Reflecting the difficult Depression economy, Jacques prioritised the use of semi-precious stones, which were not only considerably more economical, but also readily available in a variety of geometric cuts. This gave the designers the opportunity to come up with an almost architectural look in accordance with the fashions of the time. Topaz was generally combined with diamonds or gold: “The only requirement,” Vogue would explain in its October 1938 issue, “is that topaz jewellery must look as important as if it were emeralds or rubies. That is the way Cartier has treated it.” Often clients would request matching jewels: When the debutante Lady Elizabeth Paget was photographed for Harper’s Bazaar in January 1935, she wore “Cartier’s magnificent parure . . . of light and dark topaz,” comprising necklace, bracelet, shoulder clip, and large pendant earrings”.

But it was the combination of diamonds with aquamarines that Jacques particularly liked. It created, he felt, a look that was fresh and elegant and suited everyone from royalty to trendsetters. His clients agreed, as did many visiting Americans who ordered their jewels from his branch.

Of geometric design, set with oval, baguette and kite-shaped aquamarines and circular-cut diamonds, signed Cartier, fitted case stamped Cartier. @Sotheby's London, Fine Jewels, 16 July 2014

I was told by my grandfather the behind-the-scenes story of how the Cartiers put together these semi-precious stone collections. It was important—if they were to source good stones at reasonable prices—that neither the dealers nor their competitors caught on to their buying patterns. After deciding on a particular gemstone, the brothers bought them under the radar over several months, or even years. Assuming it was topaz, they would buy topazes when different gemstone dealers came to present their wares, but never too many at one time or from the same dealer. The idea was that over the course of a couple of years, they would have acquired enough highest-quality topaz to make an impressive collection for a season. And then, by showing topaz necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and bandeaux in their windows, they would make the topaz the gemstone du jour. By the time their competitors tried to copy them, not only would there be very few high-quality topazes left on the market but also the dealers would have hiked their prices and it would become almost impossible for another jeweler to create a topaz collection on anywhere near the same scale.

I read that Jacques suffered from ill-heath, eventually passing away before his brothers despite being the youngest?

Yes, Jacques continued to work in London and travel East throughout the 1930s but he suffered from ill-health as a result of weak lungs (during WW1 he had suffered from tuberculosis and been gassed at the Front). During a 1935 work trip to India with his wife, for example, instead of settling into their usual sea-view suite on arrival, Jacques had been rushed to the hospital. “Jacques has haemorrhages on arrival Tajmahal Hotel Bombay,” Nelly had telegraphed her husband’s brothers in fear. “Good doctor and nurses. Will keep you posted.” Fortunately he recovered that time but his health had taken another beating and those weak lungs remained a worry always in the background.

To manage his health, Jacques was advised by his doctors to spend time in the mountain air of Switzerland so he and his family spent the winters in the fashionable Swiss mountain resort of St. Moritz. Villa Chantarella, the chalet they rented each year next to the large hotel of the same name, became a home away from home. “Here we are again on top of the world in our Noah’s ark full to the brim of growing ones,” Jacques wrote to Pierre one Christmas, explaining how all four children were out on the slopes with their friends while he was inside in the warm working on designs for an upcoming exhibition. The ski resort was also good for business and Jacques set up a St. Moritz seasonal Cartier branch. Enticingly located next to the famous Swiss confectioner Hanselmann, Cartier’s new showroom in the mountains attracted a fair number of window shoppers over the few months it was open each year. Clients who visited the ski resort at the time included everyone from the the Aga Khan III and Coco Chanel to Hollywood stars like Gloria Swanson and Douglas Fairbanks to to businessmen like Henri Deterding, “the Napoleon of Oil,” who bought the famous Polar Star diamond from the St Moritz branch.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, Jacques’ health had significantly deteriorated. Believing he should be in his native France in war time (despite the fact he shouldn’t have really travelled from England with his ill health) Jacques spent his last months in Hôtel Le Splendid in the spa town of Dax, in the south-west of France. Sadly, he wasn’t able to receive the medical care he needed there during wartime and passed away at 57 years old.

One of his last deeds was to ask his close friend, the designer Charles Jacqueau, to train my grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier in design. For Jean-Jacques, it was a great sadness he would never be able to work alongside his father in the business, but like his father he was also an artist at heart and grew to love the design and gemstone areas of the business. He took over Cartier London in the 1940s – when the pre-war era of big necklaces and diamond tiaras had been replaced by an age of austerity and a debilitating 125% luxury tax on jewels. Just as his ancestors had done, he had to drastically change tact once again in order to keep the business afloat… but that’s a story for another time…

***

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores. You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

An Art Deco Aquamarine Diadem by Cartier London,

platinum 950, diamonds total weight c. 4 ct, aquamarines total weight c. 70 ct, signed Cartier London, reference no. 4423, workmanship c. 1930-35 @DOROTHEUM

The Dorotheum Auction Week was crowned by the sale of a rare Art Deco diadem for a sensational 582,800 euros on 10 June 2020.

The diadem was estimated € 34.000 - 70.000.

The diamond and aquamarine diadem can also be worn as a necklace.

Cartier London: The roaring 20s

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Cartier recovered and told by his great-granddaughter Francesca Cartier Brickell - PART II

Pour lire cet article en Français, veuillez cliquer sur ce lien

To read part I "He lived for design : Jacques Cartier, the lesser-known brother", click here

So Francesca, tell us more about the Cartier London operation in the 1920s: what was Jacques’ involvement in the design side?

An artist himself, Jacques enjoyed being involved in the creative process. He got along particularly well with the team of designers, who respected him for his love of their trade.

Courtesy of Olivier Bachet @Palais Royal Collection

In early 1921, he and his brothers set up English Art Works, the London workshop. Until then, Cartier London had relied on the Paris workshops that supplied 13 Rue de la Paix for its stock. The setup had worked well enough for a time, but as demand increased, it became apparent London should have its own team on the ground (as in New York). Félix Bertrand, a talented jeweler who had proved his skills setting up the American Art Works workshop under Pierre, was sent over to do the same in London. Under his leadership, and that of a fellow Frenchman, Georges Finsterwald, a team of skilled mounters, setters, and polishers were hired.

Of course, building a fine jewelry workshop didn’t happen overnight. The Cartiers sought to hire top master craftsmen, at considerable expense, and then relied on them to teach the young apprentices. The firm took on about five or six apprentices a year, mainly Englishmen (Jacques felt strongly it was his duty to offer opportunities to the English workforce), of which only one or two made it through the first year of a six-year traineeship.

The creations made under Jacques quickly found favour with the English aristocracy, both for their original designs and for the high quality of the craftsmanship. I love the example of a carved emerald necklace made for a maharaja: those emeralds were so fragile that the craftsman tasked with setting them was given 48 hours off work beforehand so he was entirely relaxed because any slight shake of his hand could cause the precious gems to crack!

Signed Cartier London. @Christie's London, Important jewels, 12 dec 2012.

There’s a fun account of Jacques as a boss by one of the apprentices: “Jacques was then what we called a gentleman. He was excitable, kind and lived for design. I learnt that everything grows from something that grew before, and the room contained a library of things that had gone before: Chinese carpets, Celtic bronze-work, Japanese sword hilts, arabesques...”. This is the basis of the family motto “Never Copy, Only Create”, which I discuss in the book (and in this Youtube video).

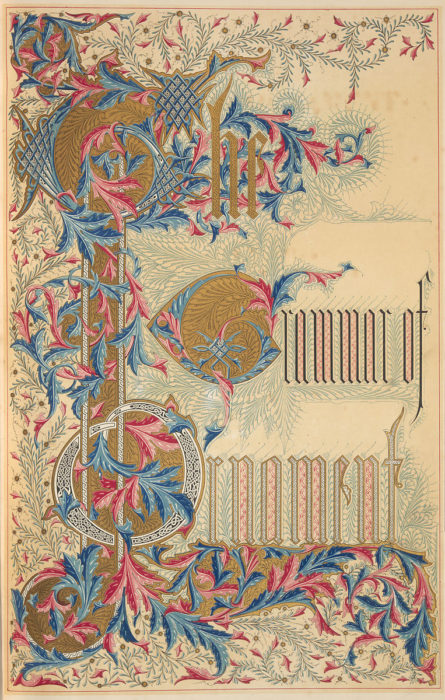

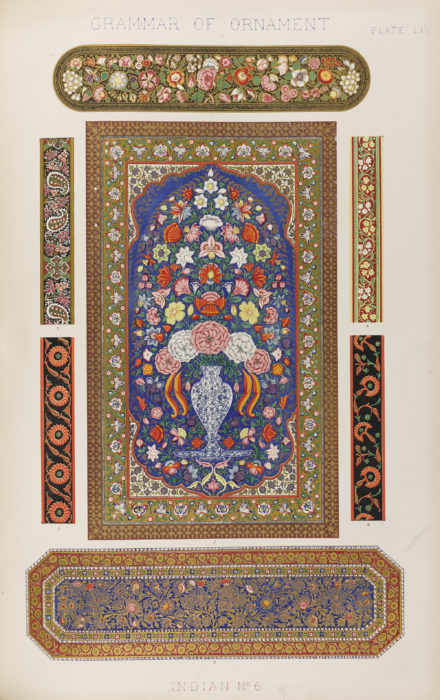

Essentially the idea was that anything and everything could and should be used for inspiration, except for existing jewelry. The brothers were avid readers of Owen Jones’ book, “The Grammar of Ornament” which had plates exploring the design principles behind the architecture, textiles, and decorative arts of contrasting cultural periods (for example, the Arabian, Turkish, Persian or Indian styles).

To what extent do you think Cartier London had its own identity in Jacques’ time?

Certainly, by the late 1920s, Jacques had succeeded in creating a distinct identity for Cartier London, so much so that he decided to buy his two brothers out of the branch. But the three branches remained intertwined, as the three brothers continued to share everything from designs to clients to gems. And though Jacques was living in England and running a British company, he never lost that sense of duty to his native France, even becoming head of the Alliance Française in London.

Jacques was not particularly social by nature but he became well-networked within British high society, thanks in part to being a savvy marketeer. He would offer jewels as prizes for charity events or lend jewellery to socialites for big events, such as the Jewels of the Empire Ball at the Park Lane Hotel, the hot invite of the day. Most evenings after work, he and his wife Nelly would dine out in London with clients, visiting French dignitaries and friends.

The 1920s were an exciting time for growth, with new money competing with old and Jacques’ acquaintances included a growing number of financiers, industrialists, and entrepreneurs, from Victor Sassoon to Captain Alfred Lowenstein (before his tragic – and mysterious – early death falling from his private plane). Clients of the London branch also covered the spectrum of English high society, from aristocrats and heiresses such as Lady Sackville (known to pop in to buy gifts for her daughter, the writer Vita Sackville-West, after their momentous rows) to a new generation of “bright young things”.

Satirized in Nancy Mitford’s and Evelyn Waugh’s novels, this fast-living wealthy bohemian group had expense accounts at Cartier and danced all night in diamonds. Their number included Nancy Cunard, Lady Abdy, Lois Stuart, the Guinness sisters, and even Daisy Fellowes whose famous Collier Hindou necklace was made in Paris but who – like many clients - shopped in all three Cartier branches: in London, she bought the 17.47ct Youssoupoff Tête de Bélier (ram's head) pink diamond which was said to have later inspired Elsa Schiaparelli's signature shocking pink.

Tell us more about Jacques’ wife, Nelly?

Nelly was great fun, a larger than life American heiress who was – on the surface – the opposite to Jacques. A Protestant who had been married before, she was living in Paris’ Avenue Henri Martin with her parents and young daughter when she met Jacques for the first time. It was pretty much love at first sight – or first meeting at least - but Nelly’s father, John Harjes, a prominent banker and the partner of J.P. Morgan (in fact, John Harjes’ bust still sits proudly in the lobby of the Place Vendome J.P.Morgan bank today) did not approve of his daughter marrying a jeweller. So he set a condition: if Jacques really wanted to marry Nelly he must prove his love by staying away from her for an entire year. Jacques agreed without hesitation. 365 days later, he returned to ask for her hand in marriage. Mr Harjes agreed and Jacques promised there and then that he would never touch a cent of Nelly’s money.

The couple adored each other. In the 1920s and 1930s, Jacques went back to India regularly and Nelly would accompany him on the trips (she travelled with 18 suitcases so she took along her personal dresser as well!) They took their chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce all the way from London but it wasn’t always plain sailing: there were times when they had to cross streams on rafts or when the Rolls had to be dismantled to make it over rocky terrain - and then put back together again on the other side! Accommodation en route varied a large amount too: one minute they might be sleeping on the floor in a basic station house, the next luxuriating in the comfort of a maharaja’s palace.

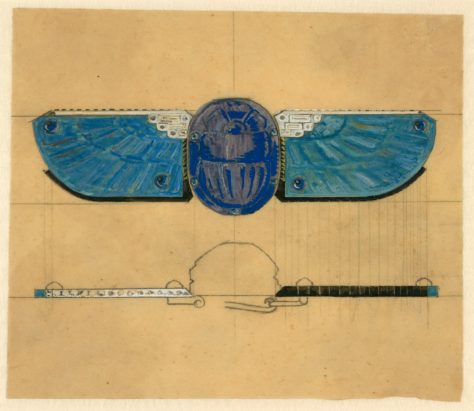

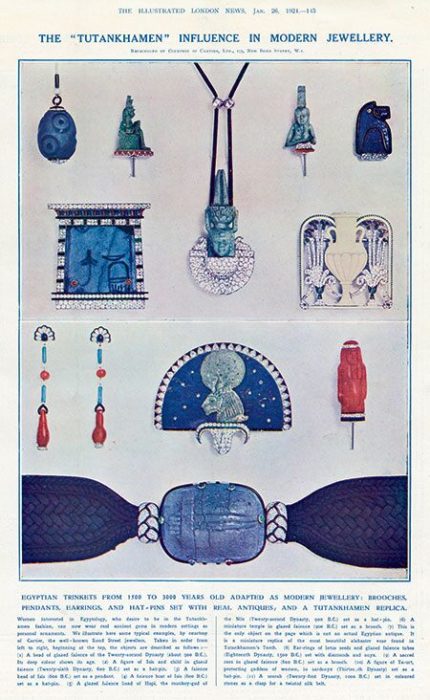

Nelly was also a great adventurer in her own right, always up for new travel in exotic places. Jacques called her wanderlust the “Va Va” as she wasn't good at sitting still : she wanted to "go go" And when she returned from those explorations – she often travelled with her best friend, Madame Fournier - he loved hearing all about them: “raconte moi ton cinema” he would say, sitting by the fire in their sitting room as she filled him in on stories from the other side of the world. When she returned from Egypt, for example, she brought back small momentos. Jacques kept a bright blue scarab beetle made from fabric/feathers: remarkably similar to the ones Cartier would later create as jewels.

Is this where the idea for Egyptian revival jewelry came from?

Well, Jacques had first visited Egypt in 1911 so they both knew the country, and there was something of an Egyptian craze in the early 1920s. When Egyptologist Howard Carter announced to the world in 1922 that he’d unearthed an opening to Tutankhamen’s tomb, and with it artistic treasures of a long-shuttered mysterious past, Egyptomania swept Paris, London, and New York.

After the deprivations of war, escapism was more welcome than ever, and ancient Egypt was suddenly all anyone could talk about. Fashion designers found inspiration in motifs like lotus patterns and the vibrant colors of Egyptian paintings. Women heaped on the black eyeliner and put their hair up to more closely resemble the glamorous beauties of the past. Bright cocktails with names like King Tut became the drinks du jour and Egyptian-themed parties were all the rage.

Jacques was similarly inspired. As photographs and articles made their way to the West, Jacques carefully cut them out of newspapers and folded them into his small black leather diary. Not many things made it into that diary, but Jacques felt that this momentous discovery had revealed works of art on “a plane of excellence probably higher than has been reached in any subsequent period of the world.”

This led Cartier London to create some truly stunning Egyptian Revival style jewels. In January 1924, there was a full page spread in The Illustrated London News Cartier London’s Egyptian creations, announcing that “Women interested in Egyptology, who desire to be in the Tutankhamen fashion, can now wear real ancient gems in modern settings as personal ornaments.” These one-of-a-kind pieces incorporated genuine antique treasures, sourced by the Cartier brothers from European antiques shops and Eastern bazaars.

The challenge was keeping the purity of the ancient style while updating it for a modern audience. This wasn’t to be a whimsical attempt to follow the fashions of the day, it was deeply rooted in authenticity. For a deep blue bead from 900 B.C, Jacques chose to enhance its color with the smallest amount of diamond and onyx on its top and base, and to make it into a simple pendant. A figure in a bright blue crescent-shaped glazed faïence was brought into focus with a subtle border of diamonds and onyx, and three-thousand-year-old stone carvings were framed in black onyx. The focus was on a simple dressing up— nothing fanciful. It had to be true to the original style and stay classic. These were ancient artifacts that had survived thousands of years—they should not be turned into elaborate pieces that might soon go out of fashion.

What about the Tutti Frutti jewels – how was Jacques involved with those?

Jacques saw the world with an artist’s eye and India made a particularly strong impression on him: “Out there everything is flooded with the wonderful Indian sunlight.. one does not see as in the English light, he is only conscious that here is a blaze of red, and there of green or yellow”. After his trips, he would meet with his eldest brother Louis and the head designer in Paris, Charles Jacqueau, and they would discuss ideas for an Indian-style of jewellery. `

This would take many forms – from carved emerald pendant brooches (like the one bought by Marjorie Merriweather Post from Cartier London) – to the now iconic tutti frutti jewels where vivid rubies, emeralds and sapphires would be boldly combined together. The colored stones might be faceted, cabochon, or carved, and the motif was often based on nature but the most important characteristic of those gems – for Jacques – was their colour. They had to be bright, bold and striking. That was the secret behind the powerful effect of the tutti frutti jewels (along with the intricate designs and exquisite craftmanship).

And what I found particularly interesting in my research was that although those Indian-inspired jewels often reach record prices at auction today (it was fun to be involved on the online Sotheby’s sale of a Tutti Frutti bracelet last month that broke records when it sold for $1.3m!), in reality the carved gems that Cartier used back then were far less expensive than larger precious gemstones (partly because any flaws could be carved out). So actually, during the 1930s they became quite good “Depression-era jewels”. I show some more examples of that style in this Youtube video.

Do you have any favourite Indian-inspired pieces?

It’s hard to say – and I am guilty of changing my mind regularly! A wonderful example of a Cartier London "tutti frutti" piece that I saw again just before lockdown at the V&A Museum (where it sits on permanent display in the jewellery gallery for those who would like to see it too!) is the Mountbatten bandeau. It’s stunning – delicate and bold at the same time and a brilliant design made to either sit flatteringly on the forehead or be split into 2 bracelets. (3 jewels for the price of 1 really!).

In my research I dived into the background of those 1920s bandeaus and discovered that in 1928, Jacques wrote to his brother Pierre telling him about a London charity fashion show that he was working on with notorious society heiress Lady Cunard. “The idea”, Jacques explained,“[was] to show what women with short hair can wear, both now and when they start to grow their hair again.” The days of pre-war big hair up-dos and heavy tiaras were over and the Cartiers quickly adapted their offerings to include a vast array of head-dresses, bejewelled hair clips and diamond crescents and circles to decorate tightly shingled heads.

The colourful Mountbatten bandeau (as it later became known) was one of over 100 pieces that Cartier made for the fashion show but it was snapped up for £900 before it even made it to the runway. The buyer, Edwina Mountbatten (1901-1960), was a strong stylish and well-connected woman who knew what she wanted when she saw it. She would also, rather aptly given her choice of the Indian-inspired headdress, go on to become the last Vicereine of India.

Did Jacques have a favourite Indian client?

Well, over time, Jacques built a relationship with many of the Indian princes, from the Maharajas of Kapurthala, Patiala, Indore, Baroda to the Nizam of Hyderabad. They chose to give their large commissions to Cartier not only because they appreciated the quality of the firm’s craftsmanship, but also because they trusted Jacques, and were appreciative of the time he had spent in the country. Of all of them, he was especially close to the Maharaja of Nawanagar. Better known as Ranji (short for Ranjitsinji), the Jam Sahib had been educated in England and was a well- known cricketer.

After Jacques’ initial trip to India in 1911, the two men often saw each other and became good friends. Jacques and Nelly were frequent visitors at his Indian palace: Nelly wrote home to her children in excitement after her first trip there in 1926 for Christmas: “I hardly know how to begin to describe the luxury we live in. Indeed what with one Rolls at our disposal and the suite in this palace built for the Prince of Wales visit (which he never came to see and hurt most frightfully His Highness as you can imagine).” After a Christmas banquet -“table decorations wonderful but no crackers or mince pies could make it a real Christmas atmosphere” – they enjoyed a “very very thrilling” panther shoot. Not very politically correct these days but interesting given the iconic Cartier panther motif!

Ranji, like many of the Maharajas, also travelled to England regularly and he would meet Jacques in London to discuss jewellery commissions or invite him and Nelly – plus the kids - to spend holidays at his Ballynahinch estate in Ireland. My grandfather recalled spending blissful summers there as a young boy, roaming free with his siblings over the enormous estate, with his Ranji as their generous host.

At the root of the jeweller’s and the maharaja’s close friendship was a sense of sharing the same values. Jacques described Ranji as “a Prince really princely in his taste as well as by the qualities of his mind and heart”. But that was not all: they also shared a love of gemstones. The stylish Indian ruler would happily wait decades for the most perfectly deep- red ruby or vivid green emerald. It didn’t have to be huge and show-stopping; he was far more interested in the quality and innate beauty of the jewel. Like a true collector, he would admire his gems even when alone, holding them in his hands and studying them under different lights just for the pleasure of it. The two men tended to agree on most things, but interestingly disagreed on the perfect colour of rubies –Jacques felt it should be deep red but Ranji preferred more of a purple hue.

Was there a favourite piece made for the Maharajah of Nawanagar?

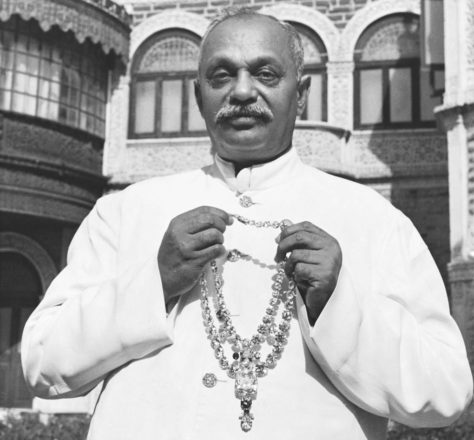

The Maharaja Jam Sahib of Nawanagar became a very important client for Cartier, commissioning museum-worthy emerald necklaces and buying figurine mystery clocks. He had a truly incredible collection of stones. Jacques’ favourite commission of all was a diamond necklace. But not just any diamond necklace: this one took three years to make, as an increasing number of superb quality diamonds kept being added to the mix, so the design had to keep being adjusted to include them!

“Had not our age witnessed an unprecedented succession of world-shaking events,” Jacques would later write, referring to the cumulative effect of the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Depression, “such gems could not have been bought at any price; at no other period in history could such a necklace have come into existence.”

In the end, the necklace included the Queen of Holland – a blue-white 136.25 carat diamond- as well as fancy blue and pink diamonds and an olive-green brilliant diamond of 12.86 carats—“A rare stone, indeed!” Jacques had exclaimed when he saw it. When the necklace was completed, the overall effect was extraordinary, a unique cascade of colored diamonds.

My grandfather told me how his father had been a very modest man who rarely talked about himself but this was one piece he admitted being truly proud of creating: he called it “a really superb realization of a connoisseur’s dream.”

Sadly, after all the work that had gone into it, Ranji did not have much time to enjoy the necklace and Jacques did not see his friend wear it again. Just two years later, Ranji would die from heart failure. His nephew and successor, Maharaja Digvijaysinhji of Nawanagar, would follow in his uncle’s footsteps, becoming an excellent client in his own right and often asking Jacques to remount old family heirlooms in the Cartier style such as the tiger’s eye diamond sarpech in 1937.

This interview will be continued next week, when Francesca will be discussing Jacques’ role in Cartier London in the 1930sCartier London in the 30’s : A decade of contradictions.

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores.

You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

A 1924 Scarab brooch with fragments of Egyptian faience. CARTIER, BROOCH, 1924. Faience, diamond (round old-cut), emerald, smoky quartz, and enamel. Vincent Wulveryck, Cartier collection. © Cartier. This brooch was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Past is Present: Revival Jewery. Exhibition from February 14, 2017 through August 19, 2018 @Museum of Fine arts, Boston

"He lived for design": Jacques Cartier, the lesser-known brother

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Cartier recovered and told by his great-granddaughter - Part I

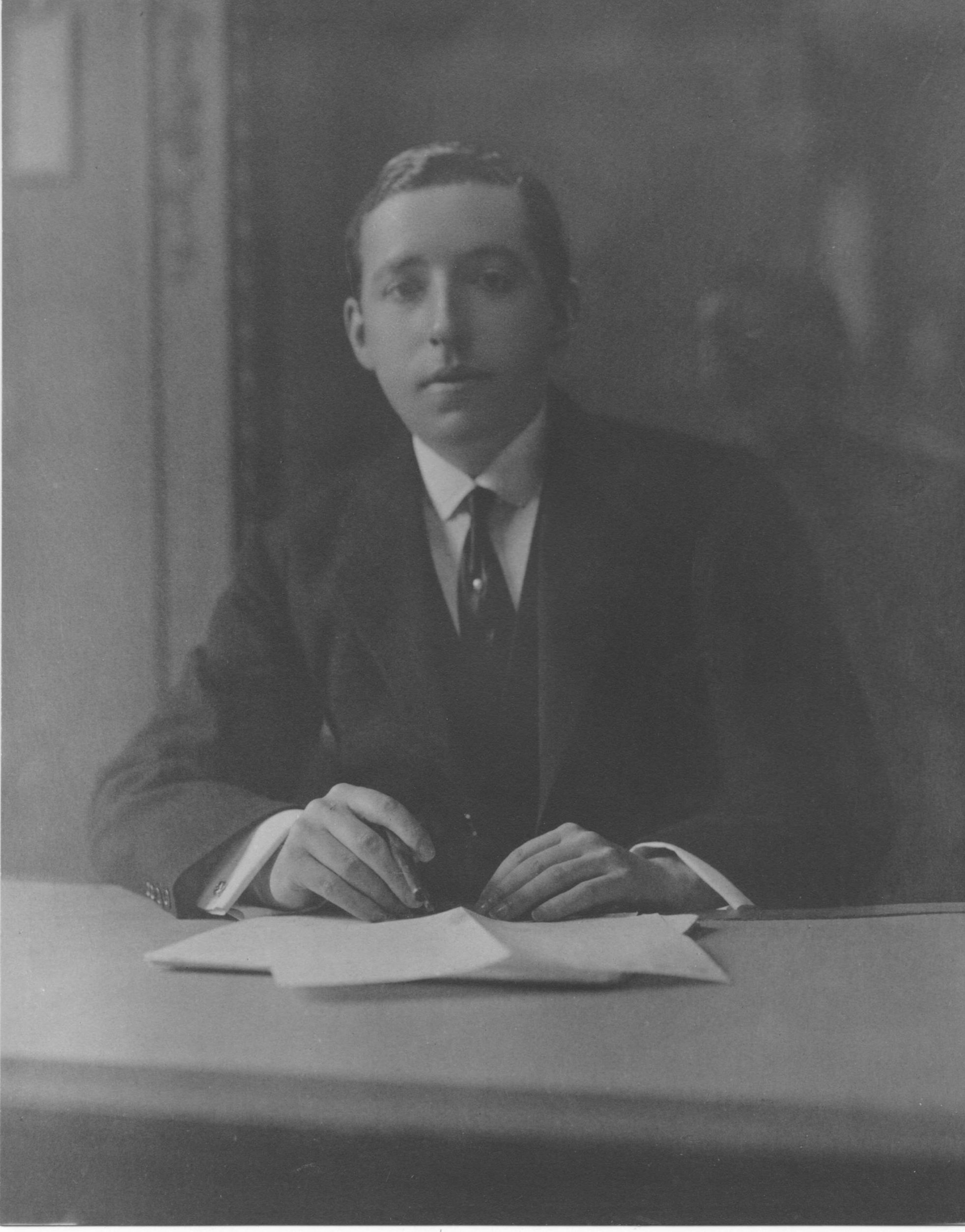

The history of Cartier in the first half of the 20thcentury is largely the story of the three Cartier brothers. Up until now, one of them has remained in the shadows: the youngest, Jacques. His elder brothers (Louis and Pierre) have been more widely discussed: Louis, who ran Paris, is often celebrated for his creative contribution to the jewellery world. He popularised the use of platinum as a mount in large diamond jewels and was the genius behind iconic pieces like the Tank watch. In America, there have been exhibitions and catalogues about Pierre and the Cartier New York business he founded. But Jacques has not been as widely discussed because there was less publicity known about him.

More recently, that changed when the discovery of a trunk of long-lost family letters prompted Jacques’ great-grand-daughter to delve into the untold story. Francesca Cartier Brickell has spent the last decade researching and writing about four generations of her family for a new book, “The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family behind the Jewelry Empire”.

I spoke to her last week to find out more about the life of this remarkable man. I am honored that Francesca Cartier Brickell has reserved for Property of a Lady this first exclusive interview in the French media !

Francesca, tell us about Jacques: what he was like and what was his role in the firm?

My great-grandfather Jacques was the youngest of the three Cartier brothers – born in 1884, he was almost ten years younger than Louis and still at school when his elder brother joined their father Alfred in the family business. Growing up, Jacques didn’t actually see himself as a jeweller: he was a gentle, artistic soul who felt a calling to become a Catholic priest. His family, however, had other ideas - his brothers told him his duty was with their fraternal trinity rather than a life spent in worship of the Holy Trinity! And so in 1906, at 21 years old, after completing his education and military service, he joined the family firm. First up was an apprenticeship in Paris where he worked in all the departments but discovered a particular passion for design and gemstones.

In terms of his contribution to the firm, Jacques was something of an all-rounder. As I explain in this Youtube video, whereas Louis was focused on the creative side (hiring designers and insisting the firm create unique pieces in the ‘Cartier Style’) and Pierre threw himself into the business side (opening branches in London and New York, traveling to Russia to meet suppliers and open an early a ‘pop-up’ shop for the Christmas season in St Petersburg), Jacques became a connoisseur of gemstones, a respected designer and a salesman who inspired great loyalty among his clients. In fact it was one of these loyal clients who wrote his obituary when he passed away: I discovered it in an old yellowing Times newspaper kept safely in the family trunk of letters all these years and I think it’s worth sharing here as it really sums him up - Lady Oxford, wife of the former Prime Minister Asquith, wrote “Jewellers are not always great artists, but this was not the case with M. Jacques Cartier. He was rarer than a great artist, or designer in precious stones: he was a wonderful friend. Completely unself-seeking, courteous to strangers, gay, kind and the best of ambassadors between the France which he loved and the England which he admired.” I was very moved to discover that because while I had grown up hearing how wonderful Jacques had been as a father, this showed the high regard in which he was held by those outside the family as well.

As I explore in my book, “The Cartiers”, the strength of Cartier in the early 20thcentury was down to all three brothers: their magic mix of complementary talents, their unbreakable bond and their shared ambition to build “the leading jewellery firm in the world.” They also had something that their grandfather (who had founded the family business in 1847) and their father Alfred had lacked: scale. There were three of them (‘three bodies, one mind’ as a contemporary of them once said), and with three they could divide and conquer. Taking a map of the world, my grandfather told me how they literally split it between them with a pencil: Louis took Europe, including the firm’s Parisian headquarters; Pierre took the Americas (he would go on to open the Fifth Avenue branch in New York) and Jacques took responsibility for clients in Britain (he would run the London branch) and the British colonies, most significantly India.

Tell us about the trips Jacques made to India, especially the first one – how did they come about?

Well, India was considered the jewel in the British Crown. Home to the Maharajas, some of the best jewellery clients on the planet, it was also the gem trading capital of the world. Jacques went on many business trips there over the years – both to buy and to sell jewels – but those trips weren’t just work for him, he came to truly love the country and its people (you can see more of Jacques’ trips to India in a behind-the-scenes video I made on Youtube).

Reading Jacques’ Indian diaries, I found it fascinating to realise how those trips had inspired many of Cartier’s creations in the 1920s and 30s. Wherever he went – from Indore, to Calcutta, to Hyderabad, to Delhi to Mumbai - he sketched and wrote about things that interested him along the way. He might note how the shape of a temple could be transformed into a brooch or how a simple lace acorn pattern he had spied in a crowded Indian bazaar had given him the idea for a diamond necklace. He had a great respect and admiration for the country and its culture – when he visits a temple, he writes: The carving of the stone … show a superior art. The ten centuries that preceded our era are one of the most wonderful periods in the history of the world. India’s share in the intellectual discoveries of these times was paramount”.

Platinum, diamonds, engraved sapphire vase, engraved rubies and emeralds. Courtesy of Olivier Bachet. @Palais Royal Collection

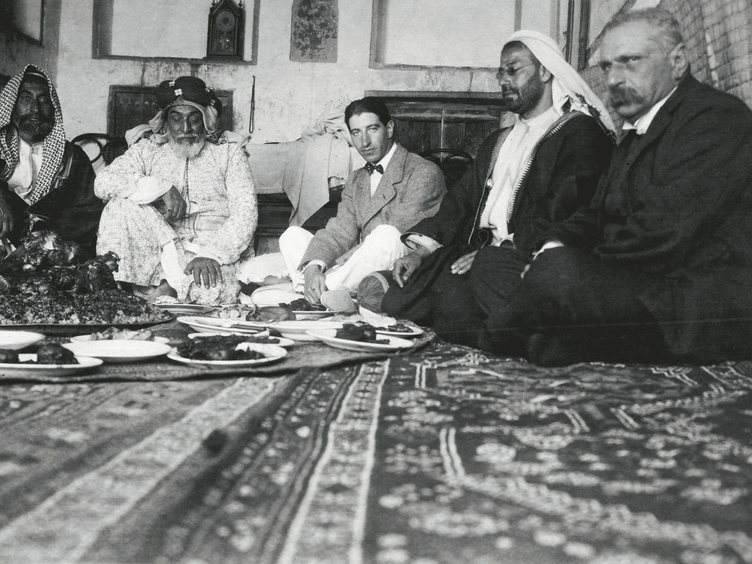

Jacques was 27 years old when he first visited India in 1911. Still unmarried, he had been working at the family firm for five years but he had lived a relatively sheltered life, only venturing overseas from Paris to London to head up the Cartier shop there. This was a far more adventurous mission: 3 weeks on a boat from Marseilles to Bombay, via Egypt, the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden. They left in the Autumn of 1911 in order to reach Delhi for the much-anticipated Delhi Durbar taking place that December. All the Indian princes would be present in Delhi to pay their respects to the new King George V and Queen Mary – and jewels would be centre stage. The Cartiers’ plan was that if Jacques was also there, he could meet multiple potential clients all in one place and hopefully also pick up the odd invitation to then visit them in their palaces.

But just to step back a moment, reading through the letters between the brothers, I discovered that surprisingly (to me at least) the main reason for Jacques taking that initial long boat trip East was not just to visit India but actually to investigate the pearl trade in the Arabian Gulf. At this stage, before the explosion of cultured pearls onto the market, natural pearls were extremely rare and valuable (to give an idea of the value: in 1917 Cartier exchanged a pearl necklace for its Fifth Avenue headquarters). No surprise then that pearls formed the lion’s share of Cartier’s income or that Cartier was keen to try and buy the pearls at source in order to ‘brand’ itself as a ‘Supplier of Pearls’ (a heading they proudly used on their invoices).

Given that many of the most sought-after and expensive white pearls were fished in the Persian Gulf, Louis sent his younger brother there on a mission that Jacques explains in a December 1911 letter: “My dear Louis, if I have understood correctly, the most important mission bestowed on me during this trip to the East was to investigate the pearl market and to report back on the most effective way for us to purchase pearls.”

The Cartiers felt that if they could meet the Persian Gulf pearl sheikhs on their own ground and begin to forge professional relationships with them, then they might be able to cut out some of the middlemen involved in the pearl trade. Most significant among Cartier’s competitors when it came to pearls were the Parisian-based Rosenthal brothers who were unique in having gained the pearl sheikhs’ loyalty and trust - and therefore had the monopoly on the pearl trade in the West, much to Louis’ intense frustration! So, on this first trip out to the East, Jacques’ traveling companion was the top Cartier pearl expert, Maurice Richard, because he needed a specialist with him who truly understood how to value pearls. After visiting the Delhi Durbar and meeting with clients in India, the pair of them - along with a translator they’d hired in Bombay - took the boat to Bahrain in March 1912. The adventure that awaited them is fascinating – meeting the pearl divers, trading with the sheikhs and the shock of eating meals sitting on the floor without cutlery! - but that’s a story for another time..

So visiting India wasn’t actually the main aim of that first trip?

I would say that, initially, it was more a by-product of that primary mission, but it became much more than that – and by the 1920s and 30s certainly, the Cartier Indian connection became absolutely fundamental to the wider business. That first trip to the Durbar though didn’t go as smoothly as planned. Much like a traveling salesman, Jacques had taken with him suitcases of jewels to tempt the Maharajas: delicate, garland-style necklaces, brooches and head ornaments. However, he soon discovered that in India it wasn’t the women who were buying the jewellery, it was the men. And they were not buying for their wives or their lovers, like they were in Europe. They were buying for themselves. So after going to all that effort of taking such valuable jewels out there – insuring them, declaring them on arrival in Indian Customs, carrying them around the country with him and so on- to his dismay, Jacques found that the most orders he received were actually for the simple pocket watches that were all the rage in Paris at the time. Although the maharajas had some of the most splendid, exotic, envy-inducing gems on the planet, they were also – so Jacques discovered –simply keen to keep up with the fashions of the West.

Signed Cartier, Paris, circa 1910. @Christie's

So did the Durbar turn out to be a disappointment?

Well, the Durbar itself was a bit lackluster when it came to sales, but it did enable Jacques to meet many of the ruling princes in their majestic tents across the Durbar encampments, including the Maharaja of Nawanagar who became a great friend. And from those initial meetings, he received invitations to visit them in their palaces across the country: sometimes he stayed in opulent palaces but at other times he was simply a traveling salesman sleeping on rough matting on the floor in basic station houses. As he travelled through the country, Jacques wrote extensive travel diaries, some of which I have based my travels on as I wanted to revisit many of the places for myself.

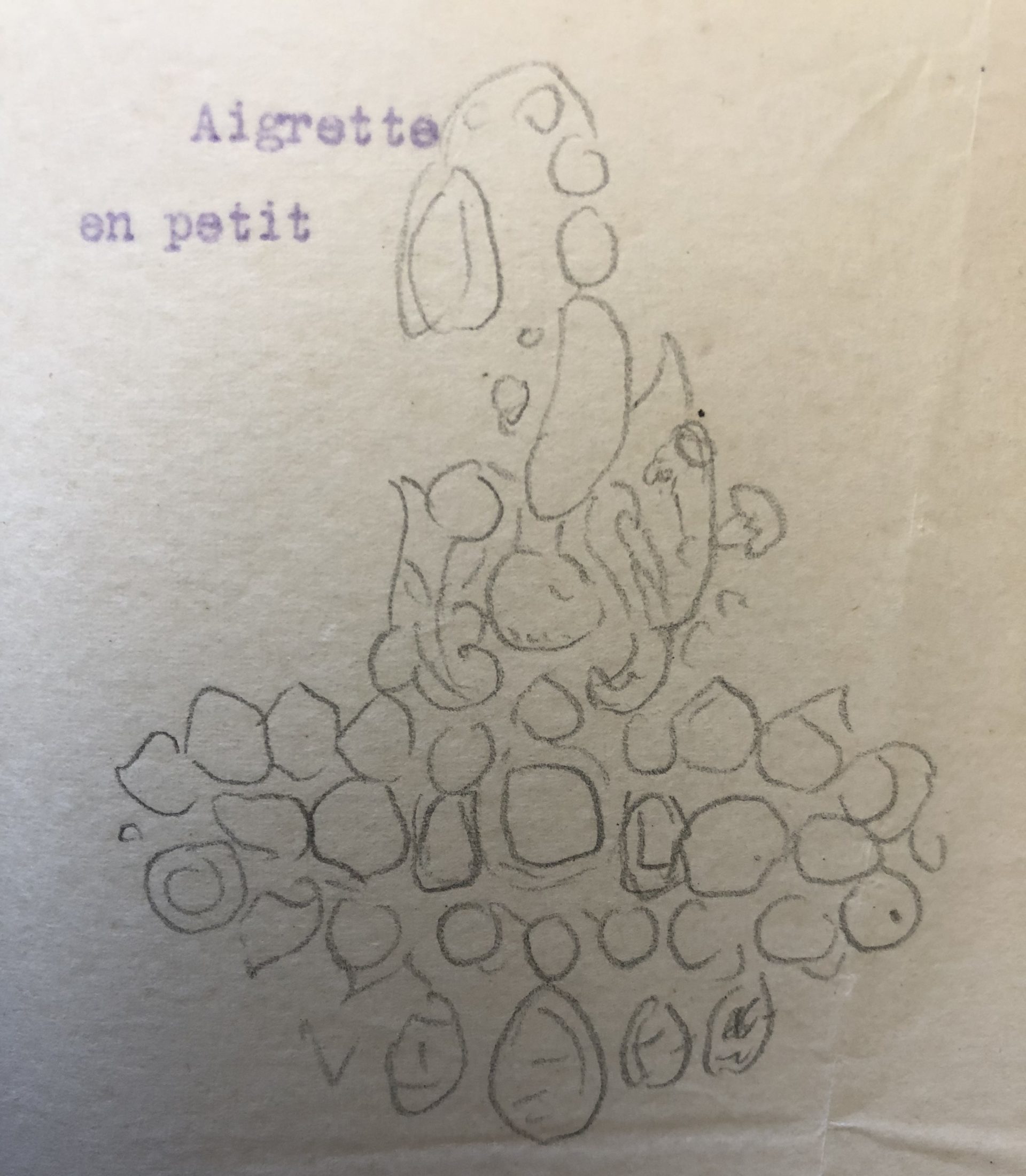

In Baroda, for example, Jacques talked about meeting the Gaekwad and Maharani in 1911 and described how he was asked to come up with designs for the resetting of the crown jewels. He spent days furiously sketching in the palace before the local court jewellers grew jealous at his presence and made him leave without securing the commission! The Maharani, however, managed to quietly give him some of her jewels to remodel. For me, it was wonderful to visit Laxmi Vilas Palace a century later and share some of Jacques’ sketches with the current Maharani Radhikaraje. When I showed her this pencil sketch from Jacques’ diary for example, she was immediately able to identify it as the diamond aigrette pictured below. That was exciting – one of those moments when past and present collide.

But Jacques was not just in India to sell jewels. As the family gemstone expert, he was always on the lookout for gems to buy as well and when he travelled, he would take his pouch of trusty “killer stones.” These were the most perfect examples of precious stones that he owned: a Burmese ruby, a Kashmir sapphire, a Colombian emerald, and a Golconda diamond. He would use them as comparison stones when buying from dealers in shaded crowded markets or from gemstone mine owners next to the sapphire pits under the bright sun or from royalty in palaces - it meant he was assured of a perfect comparison stone whatever the light was like at the time. And as he never knew when the opportunity would arise on his travels to buy gems, those killer stones were a simple way of making sure he was always prepared. When he visited the palace of Patiala in 1911, for example, the Maharaja wanted to buy a special Cartier pearl but instead of paying for it with cash he proposed exchanging it with some of his own jewels so Jacques found himself unexpectedly valuing gems instead of simply selling them.

In time, thanks to Jacques’ buying expertise and his loyal links with the gem dealers and palaces, Cartier became renowned as the jeweller with the best coloured gemstones in the world.

Tell us about WWI – did Jacques fight?

Yes – he felt a strong sense of duty to his country: my grandfather explained to me that for his father it had been “Country, Family, Firm” in that order. When WWI broke out, Jacques was actually ill with tuberculosis and sent to a sanatorium in Switzerland - but instead of being relieved to be avoiding the fighting, he just wanted to receive the best treatment as fast as possible so he could rejoin his regiment and fight alongside his fellow countrymen. His brothers took safer jobs (Pierre as a chauffeur to a general, and Louis in several office posts) and they urged Jacques to do the same. He had the perfect excuse, they told him, it would be easy to have a doctor sign him off as unfit for service at the Front given his weak lungs. But Jacques refused: he saw no reason why he should be treated any differently from his fellow soldiers. After recovering from tuberculosis, he joined his cavalry regiment at the Front, only to be gassed and sent to another hospital – this time in Lucon - for several weeks. Once he had recovered for the second time, he re-joined his regiment at the front again – much to his brothers’ exasperation - leading them into battle. For services to his country, he received the Croix de Guerre but his lungs never really recovered from the gassing and in later years, he would describe himself as living a ‘half-life’ lacking energy and struggling for breath.

After the War, the world was a very different place. Years of fighting had taken their toll on Europe and the balance of wealth – and with it Cartier’s key clients - shifted across the Atlantic. Jacques went to help Pierre with the Fifth Avenue branch (they felt they needed two family members out there to really grow the business and meet demand) before moving to England a few years later. Together with his wife Nelly and their four children, he settled in Milton Heath, a large country house in Dorking, Surrey. Every morning, as his son took the horse and trap to school, Jacques would travel the thirty miles in his chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce up to Cartier London in Mayfair. He had moved the London headquarters to 175 New Bond Street in 1909 (previously it had been a much smaller showroom below the Worth shop around the corner on New Burlington Street) and it was an impressive building. Outside, a doorman stood to attention in front of the royal warrants on the pillars, while inside walls were draped in rose-pink moire, candelabras hung from the ceiling and mirrors reflected discreet touches of gilt. It was, according to a designer who worked there in the 1920s: a “near replica of Cartier in Paris, but perhaps even more upstage than the establishment in the rue de la Paix - having an added barrier of English reserve. Anyone would think twice before entering.”

This interview continues with "Cartier London : The roaring 20s"

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores.

You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

Francesca Cartier Brickell, Photo Credit: Jonathan James Wilson

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)