Santi Jewels by Krishna Choudhary, an ode to Mughal jewellery

“My great desire is to tell the world about the rich history and culture of India through the story of my family.”

Krishna Choudhary represents the eleventh generation of a family of jewellers who have been practising their art in Jaipur since the 18th century. Of Hindu origin, named after one of India’s most revered and popular deities, Krishna has a long-standing passion for the history of the Indian subcontinent, its ancient artefacts and especially for the decorative arts of the Mughal period (1526-1857).

After graduating from Middlesex university London, he completed his studies in Islamic history and Hindu arts at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). In 2011, he completed a degree in gemology at the Gemological Institute of America. He then returned to his hometown, Jaïpur, to train at his family’s business, Royal Gems & Arts. In 2018, Krishna Choudhary moved back to London and in 2019 he opened his own jewellery house: Santi Jewels. Located in a private salon in Mayfair, Santi Jewels is characterised by elegantly understated pieces adorned with dazzling gems and multiple references to Mughal jewellery. As a whole, Krishna’s creations pay homage to his father, Santi, to the jewellery tradition of his native Jaipur, and to the even more distant tradition of India. Krishna nevertheless remains a man of the 21st century. Nourished by an ancestral tradition, he manages to break away himself from it in his own creations. We met to go back in time to discover his roots, influences and artistic tastes, references that allow us to fully appreciate the refinement of his creations.

The Choudhary family, Royal Gems & Arts and the Pink City of Rajasthan

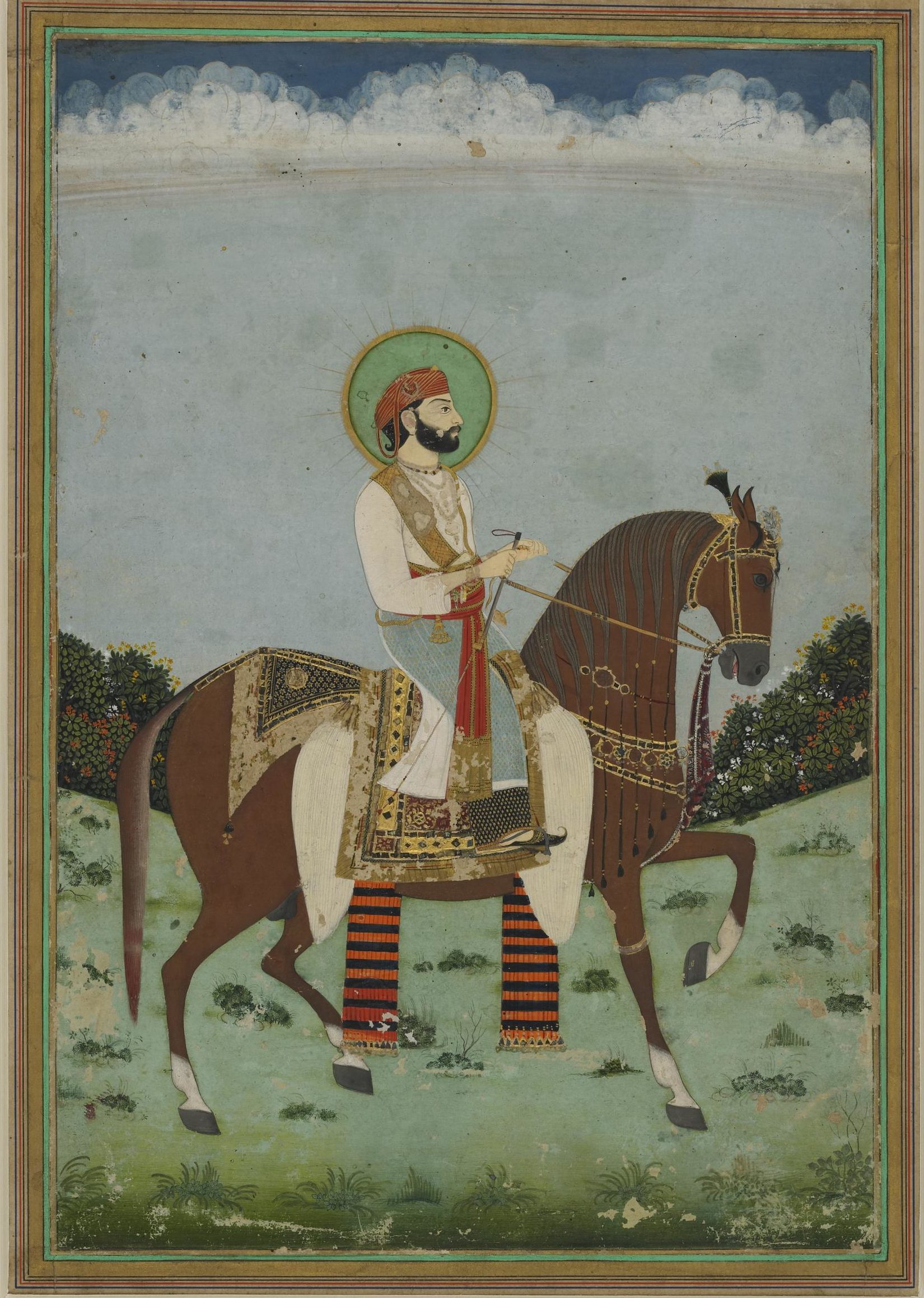

Krishna Choudhary’s ancestors came from Dausa, a town fifty-five kilometres from the capital of Rajasthan. They settled in Jaipur in 1727, twenty years after the reign of the last “Great Emperor” Mughal Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) ended. The patriarch Choudhary Kaushal Singh was initially a financial advisor to Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II (1686-1743), the founder of the city of Jaipur. He was in charge of minting coins and lending money, and also managed a Jagiri (i.e. an estate) of eleven villages around Jaipur. His role was to maintain law and order and to collect revenues and taxes. Choudhary Kaushal Singh soon rose to prominence in the Royal Court of Jaipur.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

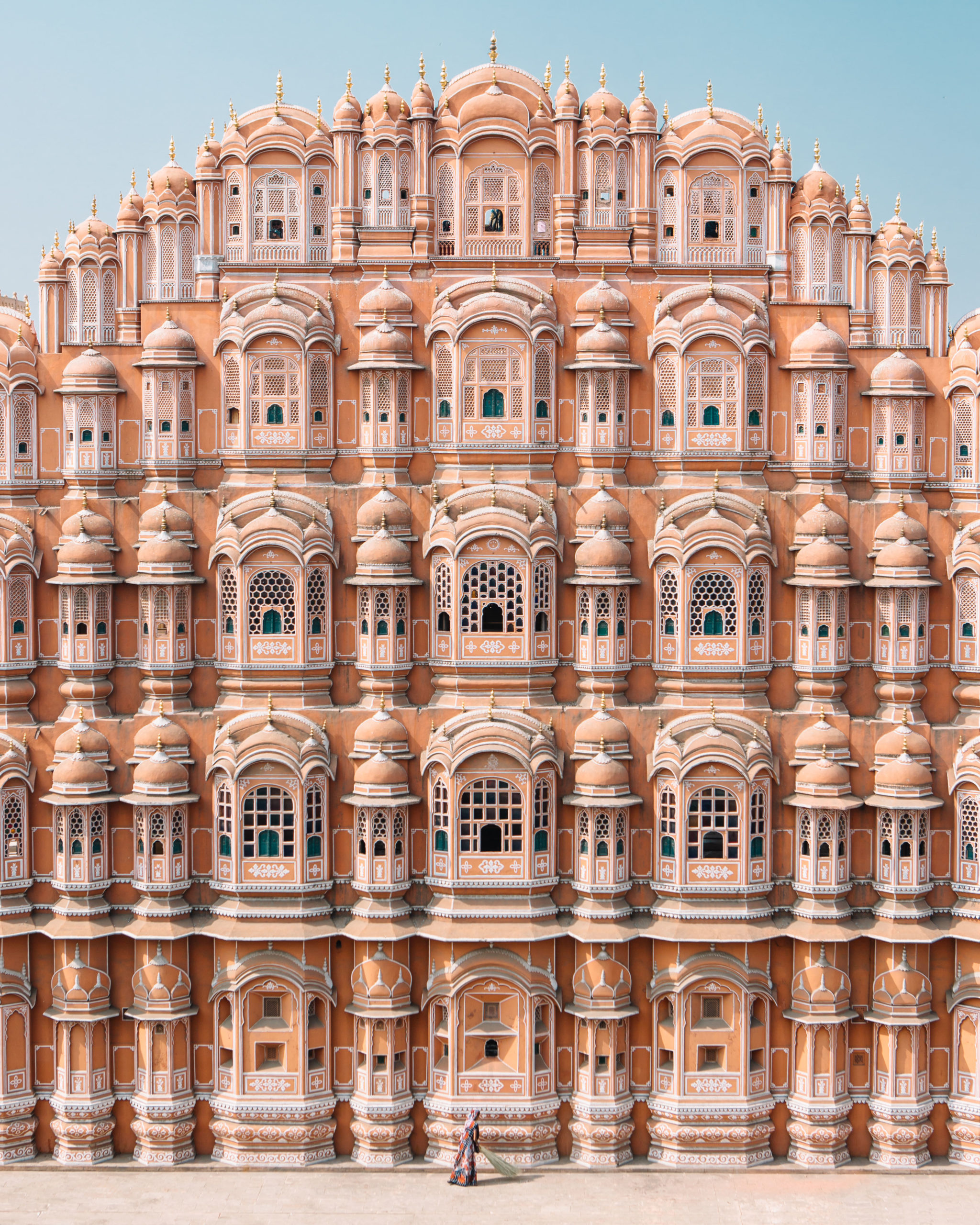

Over the decades, the “Choudharys” became gem dealers and jewellers. “This transition occurred several generations before my grandfather, says Krishna Choudhary, but although we have records going back to 1696, we don’t know exactly when”. Initially settled on the site where the Hawa Mahal, the Palace of the Winds, was built in 1799, the Choudharys then lived for a time opposite this Palace before settling permanently in the early 19th century in what is still today their family haveli “Saras Sadan”. This haveli houses the family business, Royal Gems & Arts. It is a unique place where the walls are entirely decorated with colourful frescoes from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Plants and garlands of flowers, rosettes and geometric patterns, draperies and gilding stand alongside the legends of ancient India – an innumerable pantheon of gods, Maharajas, Hindu princesses, horsemen and scattered clouds of birds. For the visitor, and I was lucky to be one, it is tempting to stay for hours in this wonderful atmosphere; fortunately for the master of the place, Santi Choudhary, the brilliance of the jewels and precious objects displayed in the wooden niches of the walls quickly attracts the visitor’s eye!

Jaipur, over three centuries of jewellery tradition

The link between Jaipur and jewellers dates back to the early 18th century, when the city was founded by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. He was a central figure in the Mughal dynasty, although he was a Hindu. At the head of his armies, he supported Emperor Aurangzeb, then his successors, and in return enjoyed imperial protection. Having become privileged and powerful thanks to this alliance, Sawai Jai Singh II brought to his court renowned artisans, including jewellers, who all participated in the development of the city and dissemination of the arts.

Three centuries later, Jaipur is a major centre for international jewellery. Professionals go there to cut and trade coloured stones. For example, three quarters of the world’s emeralds are cut by lapidaries in Jaipur! “Diamond cutting, which requires a different kind of expertise, is mainly done in the city of Surat, and its trade in Mumbai” says Krishna Choudhary.

It is also in the Pink City that 90% of Indian kundan settings are made. This setting technique appeared during the reign of Emperor Jahangir (r.1605-1627), an important aesthete and patron of the arts whom Krishna Choudhary greatly admires. The kundan consists in surrounding a gem with a thin sheet of pure gold to fix it well in its support. The manipulation is done at room temperature and the setting is done by molecular bonding. This technique of inlaying gems, still in use today, allows the jeweller to work on any type of surface (gold, rock crystal, jade) and to set stones of various shapes.

Another typical art of Jaipur is that of enamelling, even if it tends to be “not as good as it used to be”, regrets Krishna. Red, blue, green and white are the signature colours of Jaipur enamel.

Finally, the capital of Rajasthan is also renowned for its jewellery. Designers come here from all over the world to buy or have their jewellery made; as for tourists, it is “at the Johri Bazaar that they can buy gold or silver jewellery, while the Bapu Bazaar is more devoted to costume jewellery” explains Krishna Choudhary.

The Pink City, a favourite place for jewellery professionals and enthusiasts, is part of a larger and even older history of jewellery in India.

A glimpse into an age-old art: jewellery in India

Hindu beliefs about precious stones

There are many texts on the importance of coloured stones and diamonds in Vedic literature. “Each stone, explains Krishna Choudhary, has particular spiritual and cosmological significance and is classified according to a hierarchy of value”. Thus, the five most important gems are grouped under the name Maharatna (ruby, diamond, emerald, sapphire and pearl) and the next four under the name Upratna (coral, garnet, cat’s eye and yellow sapphire). The gem par excellence for Hindus is the ruby, Ratnaraj, which is associated with the sun.

“In the Hindu culture of ancient India, says Krishna Choudhary, the most beautiful stones and jewels were offered to the temples. The king came second”. However, all Hindus adorn themselves with jewellery, more or less richly, depending on their place in the hierarchy of the caste system. This is often shown in ancient Hindus statues.

@The MET Fifth Avenue

Some typical characteristics of Hindu jewellery

Hindu jewellery is traditionally mounted on yellow gold. It is brightly coloured by precious or semi-precious stones cut in cabochon, pear, shuttle-cut or presented in the form of pearls. The main colours that come to mind when thinking about this jewellery are green (emerald, enamel), red or pink (ruby, spinel, tourmaline) and white (pearls, enamel). Necklaces, bracelets and head ornaments are studded with flat diamonds, simply polished, as jewellers continue the age-old tradition of keeping as much weight as possible on the gem compared to the rough. Cultural references appear in the designs, such as the sun, certain flowers (lotus, water lilies, orchids or jasmines) or the makara, the mythological creature with multiple symbols – half terrestrial-half aquatic – and which can be recognised by its attributes: a trunk on the top of the head, a gaping mouth and the tail of a fish or marine animal at the end of the body. “This type of jewellery, says Krishna Choudhary, is very popular in India, and can be found in all the workshops in the country, with some variations depending on the state”.

According to Krishna Choudhary, the essence of Indian jewellery could be defined by this aphorism: “More is more”. In contrast, the jewellery pieces he has been creating since 2019 are characterised by “Less is more”. More than the Hindu tradition, his sensibility leads him to Indo-Mughal art, influenced by Persian culture and Islamic Arts.

The Mughal contribution to Indian aesthetics

“In the arts of Islam, the representation of the living is banned from the spiritual or sacred domain but not from the private or profane domain”, says Krishna Choudhary. Thus we find scenes of daily life (court ceremonies, hunting, romantic or warlike scenes) as well as an important animal and plant iconography on buildings, in interiors, on textiles, tapestries, ceramics, illustrated manuscripts and in jewellery.

From the time of their arrival in India in the 16th century, the Mughal emperors developed plant and floral motifs extensively in their arts. There are two main reasons for this, explains Krishna Choudhary: “The first is the nostalgia of these emperors for the gardens of the East, Babur and the gardens of Samarkand, Humayun and the Persian gardens, Shah Jahan and the gardens of Shalimar etc… The second reason lies in the symbolism of the garden which in Islam represents paradise, peace and divine grace”.

Some characteristics of Mughal jewellery

In Islamic art, there is a metaphorical language of colours. Applied to jewellery, the red of spinels imported from Badakshan (a mountainous region bordering Afghanistan and Tajikistan) expressed power and royalty. Emperors liked to wear long necklaces around their necks with spinels in the form of large oblong pearls combined with sumptuous emeralds imported from Colombia, and large pearls. The deep green of the emeralds was imbued with spiritual virtues and recalled the prophet’s favourite colour. As for the fine pearls, fished in the Persian Gulf, they symbolised purity and were the most commonly worn gems of the Mughal emperors. Krishna Choudhary sees a practical reason for the abundant use of fine pearls in Mughal jewellery: they were simply easy to wear and fitted perfectly into the Mughal’s flowing, loose-fitting clothes.

The most beautiful gems were sometimes engraved and became the central element of the jewellery. Spinels were engraved with royal titles, emeralds, protective amulets, calligraphed with verses from the Koran and/or decorated on their other side with floral motifs. Flowers and plants were represented in a naturalistic figurative style but were sometimes idealised, particularly in the designs of “celestial flowers”. The floral species of the Mughals differed from those favoured by the Hindus, notes Krishna Choudhary. The rose was a particularly beloved motif, and the Emperor Jahangir and his Persian wife Nur Jahan were devotees and encouraged its cultivation. But there were also tulips, poppies, carnations, irises, daffodils, lilies etc…

Some rare diamonds were also engraved. For example, the Shah rough diamond in the Kremlin Diamond Fund collections is engraved with the names of three of its owners: Nizam Shah (1591), the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (1641) and Fath Ali Shah (1826).

Setting technique most closely associated with Mughal jewellery is kundan, mentioned above.

Jewellery making in India (from the north of the subcontinent to the Deccan plateau) underwent a profound evolution during the Mughal period. The craftsmen of the royal workshops skilfully combined the best of the Indian jewellery tradition with Persian influences and a style was born. This style, which embraced the jewellery arts, endured despite the decline and fall of the Mughal Empire. When India came under British control in 1858, the Mughal style gradually extended its influence on Western aesthetics.

The 20th century: jewellery influences shared between India and the West?

Indian aesthetics and Mughal jewellery strongly inspired the great European jewellery houses, which reinterpreted the combinations of gems, the shimmering mix of colours, the shapes – in particular the paisley motif in the shape of a teardrop with a curved upper end – and the use of engraved stones. The major jewellery houses of the first half of the 20th century, however, resisted the use of yellow gold because platinum was in vogue. Jewellery literature abounds with extravagant stories of Maharajas from the richest princely states in India coming to London and Paris to have entire chests of precious stones set in platinum. Conversely, the influence of European jewellery in India is rarely discussed.

Krishna Choudhary recalls that under the British Raj, jewellery workshops were created in Calcutta for Europeans who came to live or visit India. Jewellery inspired by what was done in Victorian London (1837-1901) appeared between the 1860s and 1880s. This influence of European design can be seen in the shape of several late 19th century rings from the Nizam collection in Hyderabad (see Jewels of the Nizam, Usha R Bala Krishnan, p.221-223). In contrast, yellow gold remained the precious metal of choice for Indian jewellers for decades to come. Since the 1980s, a new breed of jewellers, including Krishna Choudhary, has been breaking away from it.

It is astonishing to note that since the conquest of the Great Mughals, no new foreign influence has imposed itself on India; Westerners played an important but indirect role during the last third of the 20th century.

Independence, end of privileges and abolition of the privy purse: Indian jewellery in danger

The year 1947 was marked by the dissolution of the British Empire followed immediately by India’s Independence on 15 August. At the time of Independence, there were 555 princely states covering almost half of India’s territory and about one-third of its population. Under the Indian Independence Act and the incorporation of the various princely states into India or Pakistan, the various rulers (Maharaja, raja, Nizam…) were forced to give up their power in exchange for “privy purse” (a tax-free private grant of about a quarter of what they had previously earned).

Twenty years later, in 1971, Indira Gandhi (1917-1984) abolished the privy purse. Until then, these rulers had been the main sponsors of jewellery in India: their relative impoverishment was not without consequences for the Indian jewellery market.

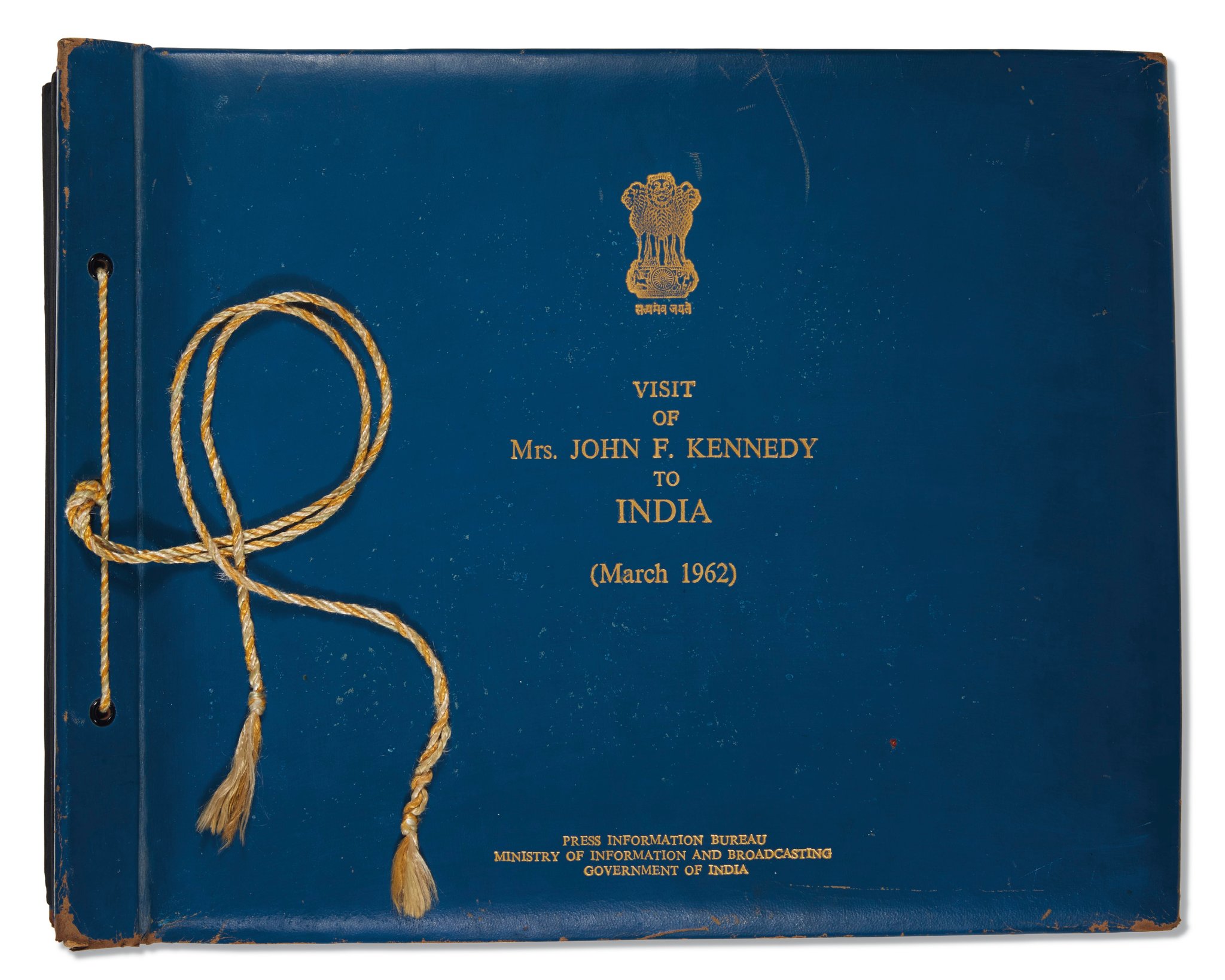

Krishna Choudhary believes that the Indian jewellery industry was able to survive after independence thanks to foreigners. Many Western jewellers, following in the footsteps of Jacques Cartier, came to India to buy gems and engraved stones, not hesitating to acquire, when possible, elements of princely finery from penniless sovereigns. Media personalities such as Jackie Kennedy and her sister Lee Radziwill contributed to the watered-down, romantic image of India, while discerning collectors such as Sheikh Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah and Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah of Kuwait came in 1975 to acquire the first pieces of their extraordinary collection of Islamic art.

“It was in the 1960s, under the leadership of my father Santi Choudhary, adds Krishna Choudhary, that our family business was renamed “Royal Gems & Arts” in order to open it up more to international trade”. Until then, trade was conducted on the floor on large Persian carpets, as seen in the photographs of Jacques Cartier’s trip to India in the 1920s and 1930s. Santi Choudhary began travelling to Europe in the 1970s to organise exclusive exhibitions of his creations. Today, Royal Gems & Arts has become an institution whose name regularly appears on the list of art exhibition lenders around the world.

Khrishna Choudhary & Santi Jewels

Krishna Choudhary is undoubtedly an heir to this long jewellery tradition. This legacy he received at birth is of immense wealth; it is also heavy with responsibility. Krishna Choudhary is aware of this. His extreme courtesy, great culture and deep modesty testify to this at each of our meetings. Krishna admits his humility in front of the treasures at his disposal. He works essentially with gems drawn from a family treasure accumulated over three centuries. The gems he uses most are the Maharatna: diamond, emerald, sapphire, pearl – but he readily replaces the ruby with spinel, the gem most associated with the Mughal Emperors.

In this spirit, Krishna Choudhary has created a pendant composed of six flat spinels of heptagonal shape coming from the same mine, of which only one, placed at the top of the motif, has been slightly re-cut. (It should be noted that Krishna Choudhary, out of respect for the historical stones for which he creates new settings, tries as much as possible to keep them in their original size. If re-cutting is necessary, it is then entrusted to the hands of the best workshops in Jaipur). The spinels of a delicate pink and perfect purity, held by four fine yellow gold claws, form the petals of a stylised flower, the heart of which is a square old-cut diamond set on brilliants. A heavy diamond dewdrop drips from the flower. The jewel rests on a black silk cord in the pure Indian tradition. A double leaf on each side of the cord, or perhaps four paisleys, rests on the collarbones. The clasp repeats the same motif, but with lines of diamonds encircling a final spinel, this one octagonal. A true testament to the flat stone in India, this jewel celebrates India’s heritage in a very contemporary style.

Krishna Choudhary likes to work with abstract, geometric figures. He has a predilection for herringbone patterns that combine geometry with movement and refer indirectly to the vast water features (pools, fountains, canals) that refreshed Mughal gardens. Two pairs of earrings of a completely different style, one in gold and diamonds cut in the shape of a paisley, the other in titanium and diamonds, symbolise this movement of water in the form of graphic chevrons.

When asked about the symbolism of the gems, Krishna Choudhary says that he does not attribute talismanic properties to the stones he works with: “I use them because I like them, because they have a history. I can be inspired by their ancient charm, but I do not rely on astrology or religion”. A proof of this is his passion for sapphires – a gem perceived by Hindus as potentially a bad omen because it is associated with Saturn. Santi Choudhary has in his private collection a magnificent Mughal-era cabochon star sapphire that is so large that it cannot be closed with the fingers. He called this exceptional sapphire “Krishna”.

Courtesy Royal Gems Jaipur. Photo Ashish Sahi

Santi Choudhary, Jaïpur, the Mughal Emperors and India are the primary influences that nourished Krishna Choudhary, but did he have other less direct natural influences? Krishna answers immediately “The Cartier brothers because they took the quintessence of Indian jewellery and magnified it. I see a distant parallel with Mughal jewellery, which also drew on the best of different traditions to create a unique style”. JAR’s unconventional designs gave Krishna the courage to dare new materials such as titanium; Suzanne Belperron (1900-1983) and her French style, and Ambaji Venkatesh Shinde (1917-2003) who made sumptuous baguette diamond necklaces for Harry Winston, are also a source of admiration for the jeweller.

Santi Jewels is aimed at connoisseurs who enjoy the dialogue between the ancient and the modern that Krishna Choudhary subtly allows in the six to seven pieces he designs each year. In a time that sometimes gives in to the conveniences of mass production, this respect for tradition, this rootedness, this ability to make the contemporary resonate with the heritage are of great cultural and aesthetic value, making each piece an event in itself.

***

Santi jewels, by appointment only

Royal Gems and Arts

3768, Saras Sadan, Gangori Bazar

Jaipur, Rajasthan 302001, India

Victoria and Albert museum

Cromwell Rd, London SW7 2RL

***

Update September 19, 2022

Selling Exhibition Jewels by Santi

20 – 23 September 2022

Phillips London

30 Berkeley Square. London W1J 6EX

Phillips presents Jewels by Santi, a selling exhibition of the exceptional new creations by designer Krishna Choudhary together with many of the historical Mughal jewels and objects that inspired them.