Between conformity and individuality : Power jewellery

By Emilie Bérard and Marion Mouchard

From the 1970s onwards, more and more women not only entered the world of work, but above all were able to aspire to senior decision-making positions in private companies and public institutions. These new functions are accompanied by a language of appearance that defines interactions in this specific context. This language consists of asserting the competence and credibility of the person wearing it through external signs such as clothing and ornaments.

This is commonly referred to as power dressing.

Dressing according to a code allows you to actively express your identity at work: “It’s kind of back to the knight and the armor. You put on your armor, and you’re ready for business[1]“. Clothing and jewellery have a social meaning. This “sartorial engineering[2]” is conveyed by manuals such as John Terence Molloy’s famous Dress for Success book[3] and The Yuppie Handbook, which describe the silhouettes of young urban professionals. They define what is appropriate and socially acceptable in the workplace.

A stereotypical image of the businesswoman emerges, based on a balance of opposing principles: masculinity and femininity; conservatism and fashion sense; conformity and creativity[4]. The first antagonism can be illustrated by the requirement to wear a skirt suit to work. This uniform was a counterpart to the men’s suit, allowing women to fit into a predominantly male environment while at the same time differentiating themselves from it. The skirt emphasises a clear separation between the sexes in a 1980s society that was returning to conservative values while redefining them at the same time.

Jewellery, like other accessories such as scarves, also contributed to the feminisation of the costume. They also crystallise the other two opposites of women’s professional wardrobes.

A- Brand prestige and functionality

One of the most striking aspects of power dressing is the desire to conform to a group, in this case a professional entourage.

Dressing and behaving similarly among employees reflects shared values and goals. The success of the company is a common goal that is expressed through a generalised codification of appearance, thereby erasing individual specificity. The introduction of the suit, with trousers for men and often a skirt for women, corresponds to the standardisation of employees. Uniforms were supposed to be neutral in colour – beige, grey and navy blue were the preferred shades – with little decoration and a classic cut. It was part of a conservatism that was widespread in companies in the 1980s.

This uniformity was combined with a desire to display socio-economic status through appearance.

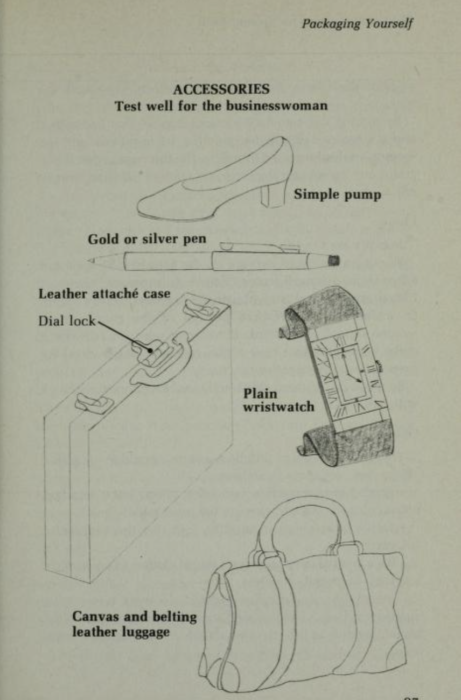

In the case of jewellery, John Molloy’s main recommendation is to “buy […] better pieces of jewelry[5]“. The biggest mistake is to wear one or more pieces of poor quality jewellery. He advises: “Instead of buying four or five pieces cheaper pieces throughout the year, [the business woman] should buy one good piece[6]“. All the more so as he advocated a sensible economy in the amount of jewellery worn: “The jewelry guideline for the businesswoman is simple: the less jewelry she wears, the better of she is [7]“. He was responding to the jewellery practices of the late 1960s and early 1970s: “A good guideline is not more than one ring at a time for business. A woman whose ears are pierced should wear simple gold posts. Dangling earrings are out. Anything that clangs, bangs, or jangles should be avoided[8]“. In this way, he opposed the principles of accumulation and aesthetic ostentation that characterised the period between 1965 and 1975.

In short: “If [a business woman] wears any jewelry at all, it should be functional[9]“.

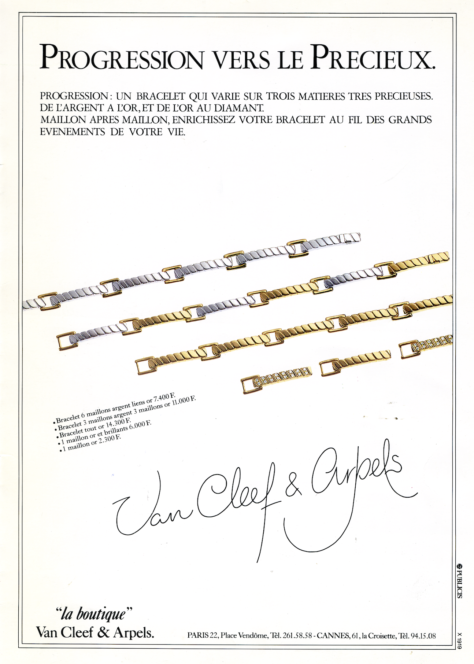

An answer lies in an invention by Philippe and Jacques Arpels[10].

Philippe and Jacques Arpels wanted to market a six-strand bracelet in La boutique that would be “accessible to all budgets[11]” and yet bear the Van Cleef & Arpels signature, a guarantee of quality and prestige. (Born in the post-war economic context and at the beginning of the Trente Glorieuses, La boutique is the sales space opened by Van Cleef & Arpels in 1954 at 22, Place Vendôme to introduce a wide range of jewellery and objects at reasonable prices to a new clientele).

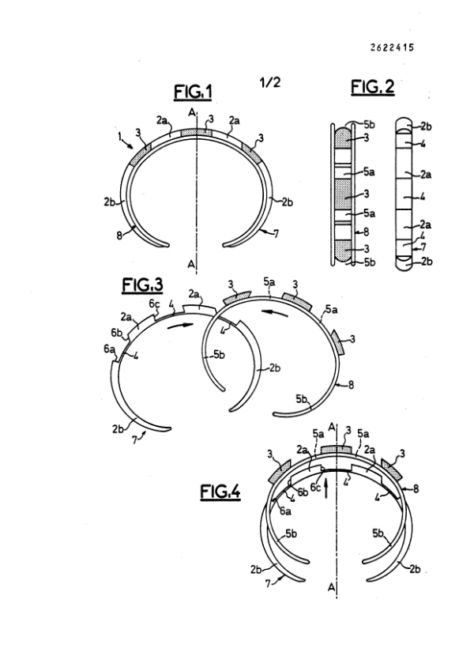

Called Progression and patented in 1983[12], this transformative piece of jewellery consists of a modular bracelet made up of a series of elongated motifs linked by square links. The motifs are hollow on the back, with two notches at one end and a pivot pin at the other, forming the link that connects each motif. This link fits into the notches of the next link and is held in place by a piston. To join two links together, simply remove the plunger, insert the link from the second link into the notches and replace the plunger. These links can be made of silver, gold or gold set with diamonds, “so that a customer who has bought the basic version can then add to her bracelet link by link, according to her means”[13]. Like the traditional pearl necklace given to a young girl on her eighteenth birthday, to which a pearl is added each year[14], “this piece of jewellery symbolises progression, the different stages of a life, the different stages of a woman’s life, the different stages of a man’s life[15]“. Because the links could be changed “very quickly and easily[16]“, the Progression bracelet was aimed at “the women of our time[17]“.

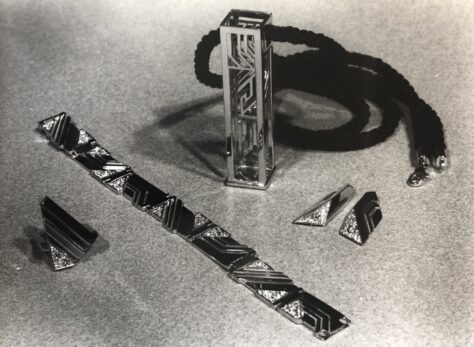

Also in 1986, after a year of reflection, Jean Vendome invented the Compact[18].

An original piece of jewellery, it takes the form of a rectangular pendant into which a ring, a pair of earrings and a bracelet are fitted. Only a few examples of this innovation were produced, but each one is unique and has its own decoration. Jean Vendome designed it for “the modern woman, a woman who works during the day but wants to be more elegant in the evening when she goes out[19]“. In its pendant form, the Compact can be worn during the day. In the evening or on special occasions, the set can be unfolded and all or some of the pieces worn. In this way it meets John Molloy’s functional requirements. While Molloy also recommended wearing an appropriate number of jewelled ornaments, he also indicated that they should “add presence”, citing as an example “a large, expensive pendant can add presence[20]“.

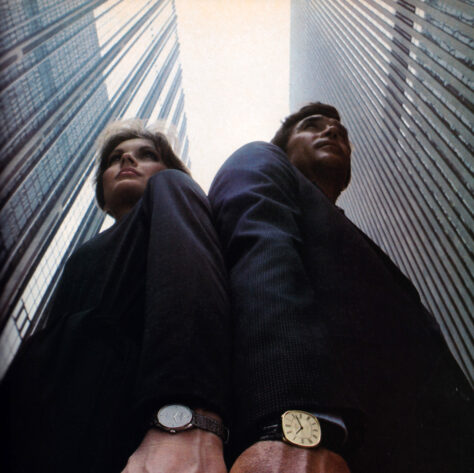

Among the jewellery accessories most likely to suit a working woman’s life, John Molloy recommended a watch, specifically a men’s model whose proportions would have been adapted to a woman’s wrist[21].

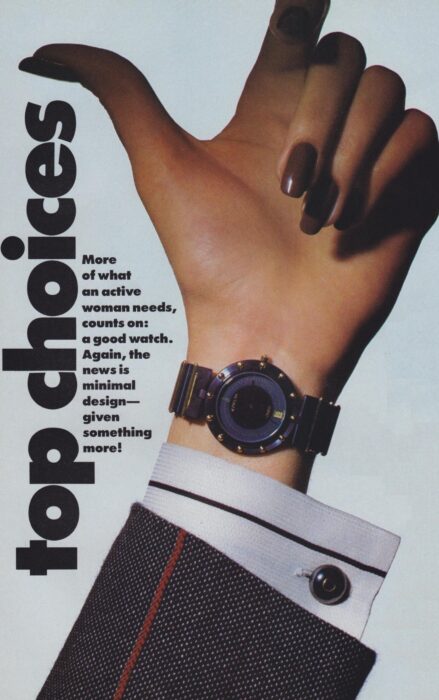

An article in Vogue echoes this recommendation: it shows a Corum men’s watch on a woman’s wrist. Although the hand is manicured, it contrasts with the sleeve of a shirt adorned with cufflinks and a suit jacket whose “play of stripes” is described as “masculine”[22] . By way of description, the magazine states: “More of what an active woman needs, count on: a good watch “; before continuing: “The best watch now: functional, simple… [23]“. John Molloy’s advice can also be found on the cover of the Yuppie Handbook, which shows a businesswoman wearing a Cartier Tank watch. The watchmaker’s model, which had been constantly updated since its creation in 1917, was adapted in vermeil for the Must range in the 1970s, contributing to its wider success.

The uniformity of appearance encouraged employees to consume the same products and brands. The silhouette became a list of the big names in fashion, jewellery and leather goods, reflecting the purchasing power of this social category. The language of brands, used to excess, sometimes to the point of caricature as described by Bret Easton Ellis in his novel American Psycho, is an outward sign of belonging to a group. That’s why the design of costumes and accessories must be identifiable.

The jewellery houses have understood this and have adapted their production accordingly. The production of multiple copies of jewellery or watch models that have become the personification of a brand – such as the Tank watch from Cartier – or, more obviously, that ostensibly bear the brand logo, accounts for a significant proportion of the turnover of the major houses. A version of the advertisement for the Tank watch, reproduced here, bears the slogan: “If you want to wear the watch that has been worn by people at the top since 1904, wear Cartier”.

B- Interchangeable jewellery: towards personalised power dressing

This form of conformity, which is inextricably linked to power dressing, leads to a loss of individual identity when taken to an extreme. More broadly, conformity runs the risk of obscuring one’s personal skills, thus hindering upward mobility within the corporate hierarchy.

Gradually, during the 1980s, women’s wardrobes began to take on a more rational freedom: a wider range of colours, patterns, materials and cuts were incorporated, thanks to the combination of different garments and accessories. In certain fields, such as the media and public relations, outward signs of creative ability are even more encouraged.

One of the main vehicles for this aesthetic variety is interchangeable jewellery.

Although similar pieces of jewellery already existed in the 1930s[24] and regained popularity in the 1970s[25], they multiplied in the 1980s. Beginning with the creations of Marina B., who, since 1978 and her Pneu jewellery collection, has been constantly inventing models of earrings with removable ornaments: JP (1982), Pneus Perles and Alexia (1983)[26].

In 1984, still for La boutique, Van Cleef & Arpels created the Nattes necklace and its derivatives in bracelets and earrings, based on a yellow gold and diamond motif into which fine pearl, haematite or chrysoprase braids are inserted.

In 1988, it was Jean Vendome’s turn to develop his Bulles et Boules[27] collection, with jewellery featuring a gold or silver pearl setting in which a spherically shaped gemstone is embedded. This gem, often a decorative stone, can be removed and replaced with another to vary the colours of the jewellery.

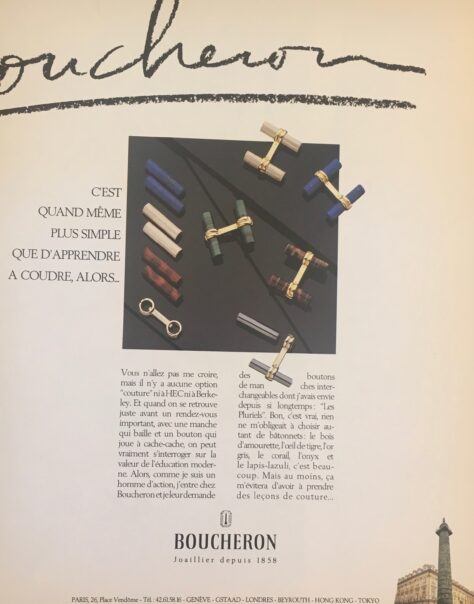

The same system is applied to Boucheron’s men’s jewellery, in the form of cufflinks called ‘Les Pluriels’: two rings connected by a yellow gold plate hold sticks of amourette wood, lapis lazuli, tiger’s eye, malachite, onyx or even white gold. These can easily be removed from their settings and replaced with another material. Boucheron praised the convenience of this invention with the slogan: “It’s easier than learning to sew[28]“. The advertising text accompanying the illustration of these cufflinks reads: “You won’t believe me, but there’s no ‘sewing’ option at HEC or Berkeley. […] So, because I’m a man of action of action, I went to Boucheron and asked them for interchangeable sleeve buttons[29]“. Pluriels were also used in women’s jewellery in the form of rings, bracelets and gold Creole ear motifs with gadroons, forming a “base” into which an “intercalary” motif in metal, coral or wood was inserted[30].

In watchmaking, the second half of the 1980s also saw a proliferation of models with interchangeable bracelets.

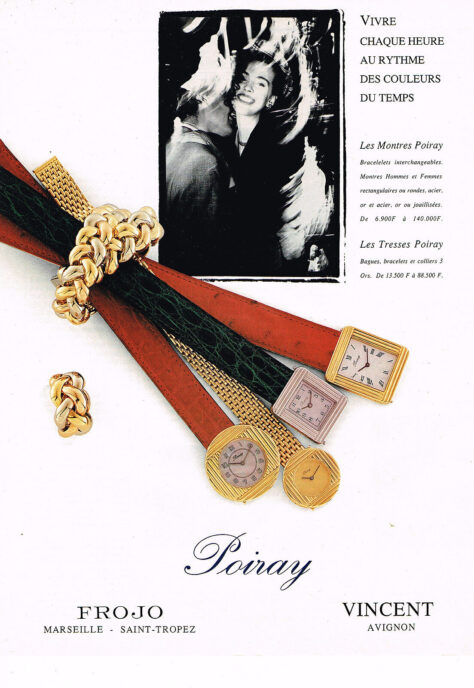

Boucheron extended its range of interchangeable jewellery with a series of watches for men and women whose dials – sometimes round, square or rectangular – were fitted with push-buttons allowing the bracelet to be easily released and replaced. Poiray’s Ma Première watch, designed in 1986, was also a resounding success. Its square case was equipped with a ratchet opening system for changing the strap. As a result, bracelets were available in a wide range of colours and materials. Nathalie Hocq, Poiray’s artistic director at the time, was a big fan when she presented this new watch on the set of Antenne 2[31] for “the woman of today, [the woman who] lives actively”.

While the introduction of a wider range of choices creates greater freedom in the way people dress, it also creates uncertainty about what is and is not appropriate to wear in a professional context.

The meaning of clothing and jewellery becomes more ambiguous, and power dressing loses its relevance in the West at the start of the new millennium.

*** To be continued! ***

[1] Testimony reported in: Patricia A. Kimle, Mary Lynn Damhorst, “A Grounded Theory Model of the Ideal Business Image for Women”, Symbolic Interaction, vol. 20, no. 1, 1997, p. 57.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The first volume of the Dress for Success manual was published in 1975 for a male audience. It was not until 1977 that The Woman’s Dress for Success Book was published.

[4] P. A. Kimle, M. L. Damhorst, “A Grounded Theory Model of the Ideal Business Image for Women”, op. cit. p. 51.

[5] [5] John T. Molloy, The Woman’s Dress for Success Book, New York, Warner Books, pp. 89-92.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Although the patent mentions Philippe Arpels as the inventor, a letter from Dominique Arpels dated 25 April 1983 attributes the idea for the Progression bracelet to his father, Jacques Arpels.

[11] [Anonymous], “Van Cleef & Arpels. Un bracelet nommé ‘Progression‘”, Figaro Magazine, 20 May 1983, n.p.

[12] Patent no. 2 540 364 for a “detachable articulation system applicable to articles of jewellery such as bracelets, necklaces, etc.”, filed on 3 February 1983, INPI archives (reference: FR2540364_B1).

[13] Letter from Dominique Arpels dated 25 April 1983, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

[14] “Dad’s idea is a little inspired by the ‘add a pearl’ necklace”. Letter from Dominique Arpels, 25 April 1983, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

[15] [Anonymous], “Van Cleef & Arpels. Un bracelet nommé ‘Progression‘”, op. cit.

[16] Letter from Dominique Arpels, 25 April 1983, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

[17] [Anonymous], “Van Cleef & Arpels. Un bracelet nommé ‘Progression'”, op. cit.

[18] Sophie Lefèvre, Jean Vendome. Un demi-siècle de création de bijoux contemporains, cat. exposition, Lyon, Muséum d’Histoire naturelle (6 November 1999-27 February 2000), Paris, Somogy, 1999, pp. 176-177.

[19] Marlène Crégut-Ledué, Jean Vendome. Les voyages précieux d’un créateur, Paris, Éditions Faton, 2008.

[20] J.T. Molloy, The Woman’s Dress for Success Book, op. cit.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “A play on menswear stripes, in a jacket, the cuff of a shirt. [Anonymous], “Top choices”, Vogue, August 1984, p. 322.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Among other examples, Raymond Verger filed a patent in 1932 for a “ring with interchangeable stone” (INPI, code: FR737464).

[25] An example is Gilbert Albert’s Bagatelle ring (1970), a principle also used by Chaumet in the same decade.

[26] Viviane Jutheau, Marina B. L’art de la joaillerie et son design, Milan, Skira, 2003.

[27] Sophie Lefèvre, Jean Vendome. Un demi-siècle de création de bijoux contemporains, op. cit., p. 147.

[28] Boucheron advertisement for “Les Pluriels” cufflinks, 1980s, Paris, Bibliothèque Forney.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Boucheron advertisement for “Les Pluriels” jewellery, 1980s, Paris, Bibliothèque Forney.

[31] “Plateau: Nathalie Hocq”, Antenne 2, October 7th, 1987, Paris, INA (code: CAB87034614).

***

Émilie Bérard has a Master’s degree in History and Art History from the University of Grenoble-II and the University of Salamanca, and a diploma in Gemology from the Gemological Institute of America. For ten years she was Head of Heritage at the jeweller Mellerio International and has contributed to a number of publications, including the collective work Mellerio, le joaillier du Second Empire (2016).

She joined Van Cleef & Arpels in 2017 as Head of Archives and is currently Head of the Patrimony Collection.

Marion Mouchard holds a Master’s degree in Art History and Archaeology from the University of Paris IV-Sorbonne. She wrote two memoirs on the jeweller Pierre Sterlé (1905-1978) and the watch and jewellery designer and manufacturer Verger (1896-1945).

A doctoral candidate in art history at the Centre André-Chastel, she is working on a thesis on archaeological jewellery in the second half of the 20th century.

Please click on this link to subscribe to the Property of a Lady newsletter