Cartier London in the 30’s : A decade of contradictions

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Théodule Cartier (1884-1941) recovered and told by his great-granddaughter Francesca Cartier Brickell – PART III

What were the 1930s like for Cartier?

My grandfather [Jean-Jacques Cartier] used to tell me how, after the boom of the 1920s, the 1930s brought such terrible challenges for Cartier and other luxury firms, many of whom did not survive. The Great Crash began in October 1929. In just two days, the U.S. equity market lost a quarter of its value, devastating investors, and over the next three years, as the Great Depression took hold, there was wave after wave of banking panic. “Eighty percent of our orders were canceled” Pierre Cartier reported to the American press in 1930. And for those clients that remained, “the Maison had to grant credits varying from six months to a year.”

For Cartier, the difficulty was exacerbated by the sudden decline in demand for the gem that had, for several decades, represented the lion’s shares of their income: pearls. The steady rise in commercially available cultured pearls had put the natural pearl market under increasing pressure since the late 1920s. In 1930, prices for natural pearls plummeted by 85 percent. Cartier suffered considerably as a result: my great-grandfather [Jacques Cartier] said this crashhurt business almost more than the effects of the Depression.

One saving grace during this period was the Cartiers’ – by now well-established – links with India. Not only did the firm continue to receive large commissions from the maharajas at a time when wealthy Americans were reigning in their spending, but also the fashion for Cartier’s Indian-inspired jewellery (including the colourful jewels later referred to as ‘Tutti Frutti’) helped keep the firm ahead of the competition in the West.

New York, 19 June 2019

I recall you writing that the centre of gravity shifted away from Paris to London?

Yes, one thing that’s not widely known is that, by 1925 already, Louis Cartier had stepped down from the Board of Cartier SA in Paris. In the 1930s, Louis was already in his early sixties and effectively retired, spending a significant time away in his Budapest palace (he had married a Hungarian countess) and his Spanish villa in San Sebastian. My grandfather said that Louis used to turn up announced in Paris after weeks or months away and move between the workshops and Rue de la Paix showroom like a ‘meteor’, tearing strips off his team for anything that wasn’t up to his almost impossibly high standards. He’d then disappear again, creating something of a power vacuum in Paris which Louis tried to fill initially by putting his son-in-law Rene Revillon in charge. Unfortunately this only led to more problems, ending in the most unexpected family tragedy, and it really wasn’t until Louis’ brilliant protégé, Louis Devaux, took over in the late 1930s that this power vacuum in Cartier Paris was resolved.

I found it fascinating to read the letters between the brothers which revealed the human behind-the-scenes reality to the flawless impression that the family strove to give the world in their calm beautiful showrooms. Pierre and Jacques, for instance, were worried for the business but they were also concerned for their older brother, admitting to each other (even if they kept it secret from the world) that on occasion they had no idea where he was or when he would be back. Louis still came up with new ideas in this period, and he kept pushing his team to innovate (in one letter asking them to come up with “something tastier, or something new”) but those long absences and the need to be alone were the flipside, perhaps, to his creative genius.

There was also a big argument between Jacques and Louis in the early 1930s. I won’t go into the details here, it’s all in the book, but save to say, relations took a nosedive for a while. In a fit of anger, Louis refused Jacques access to Cartier Paris: “The worst aspect is the sanction taken by LC [Louis] with regard to JC [Jacques]—JC forbidden to enter S.A. locations at 4 or 13 Rue de la Paix. Cessation of all relations between the two companies, no S.A. stock to be sent, ordered, or repaired. Only current business to be conducted, no new business to be carried out.”

Despite this, Cartier London was perhaps the best placed branch in the 1930s as it benefitted not only from the relationship with Indian clients (who Jacques had been visiting for the past two decades), but also the ongoing custom of the British royal court.

These aristocratic clients were not only generally less negatively impacted by the Great Depression than many of Pierre’s clients over the Atlantic, they (and their jewels) also often appeared in the social columns, resulting in the ideal type of marketing for Cartier.

whole-plate glass negative, circa 1909. Given by Bassano & Vandyk Studios, 1974. Photographs Collection © National Portrait Gallery, London

For example, Lady Granard, daughter of the American financier Ogden Mills and wife of the Earl of Granard, had been known in British high society for her love of gems ever since The Washington Post had remarked of her 1909 debut in Parliament that “after the Queen, who wore the crown jewels, no woman in the chamber wore so many splendid gems as the new American countess, and if the Queen had not worn the Cullinan diamonds for the first time, the American countess would have outshone Her Majesty.” Two decades later, though the British capital may have been under the shadow of the Great Depression, court life – and with it the requirement for big jewels – continued. In 1932, Lady Granard commissioned a truly remarkable necklace from Cartier London: it incorporated two thousand diamonds and an enormous rectangular emerald of 143.23 carats (all the gems were her own).

The London branch’s association with the British royal family was bolstered further in 1933 when Queen Mary asked to exchange a gift she had been given from Cartier for a more valuable clip brooch. After Cartier made the exchange for free, the Queen thanked the firm by visiting its New Bond Street store. Looking through the showrooms and the various departments upstairs, “Her Majesty,” Cartier’s director Joseph Sinden recalled, “talked to quite a number of the workmen and the visit lasted an hour and a half.” She had entered through the side entrance on Albemarle Street, but by the time she left, “the news had got round that Her Majesty was here and there were a number of people waiting to watch her leave.”

News of the royal visit was excellent for business. “Bond Street is busy,” Jacques reported a couple of months later; “the workshop is blocked with orders.” Her much-reported visit would also help publicize the fact that although Cartier was a French firm, the London branch employed Englishmen. This was an important message to convey at a time when there was a backlash against firms in London employing foreign workers over British ones.

Later in the 1930s, when Paris was struggling from political and social unrest, London was also busy with 27 tiara commissions for the 1937 coronation. Two years earlier, Vogue declared tiaras had made a comeback in England (“tiaras are all the rage”) and in 1936, Cartier made a diamond and platinum tiara with a cascading scroll design that the future King George VI would buy for his wife, Queen Elizabeth. This piece, known as the Halo tiara, would subsequently be worn by four generations of the royal family, making a special appearance in 2011 when Catherine Middleton (the future Duchess of Cambridge) wore it for her wedding to Prince William. Other significant 1930s royal clients included the future Duke of Windsor, whose purchase of a Cartier emerald engagement ring for Wallis Simpson would effectively lead to his abdication.

A diamond ‘halo’ tiara formed as a band of 16 graduated scrolls, set with 739 brilliants and 149 baton diamonds, each scroll divided by a graduated brilliant and with a large brilliant at the centre; original red leather box, with later Garrards label. @Royal Collection Trust. All rights reserved

Tell us about Wallis’s engagement ring?

Well, fortunately for Cartier, the Duke of Windsor (then the Prince of Wales) had favoured Boucheron when buying gifts for his previous mistress, Freda Dudley Ward. When he started a relationship with Wallis, he was apparently instructed by her to switch allegiance from one French jeweller to another because she didn’t want anything reminiscent of his previous lover!

The Prince showered Wallis in jewels. A regular to Cartier London, he would generally use the back entrance on Albemarle Street (in order to avoid being spotted by the public) before being discreetly ushered into one of the private client rooms by a waiting salesman. For a high-end jeweller, discretion was the name of the game and for a future king conducting a romantic liason with a married woman, it became particularly important. For most of 1936, the scandalous relationship was successfully kept out of the British press. In fact, Jacques, as one of the King’s trusted jewellers, would have been one of the very few who knew of its significance.

I love the story of the Wallis’ engagement ring. Traditionally, emeralds are not used for engagement rings. Compared to diamonds, the stone is soft and can scratch easily with everyday wear. But King Edward VIII (as he was for a very brief period after his father died and before becoming the Duke of Windsor) wasn’t interested in tradition.

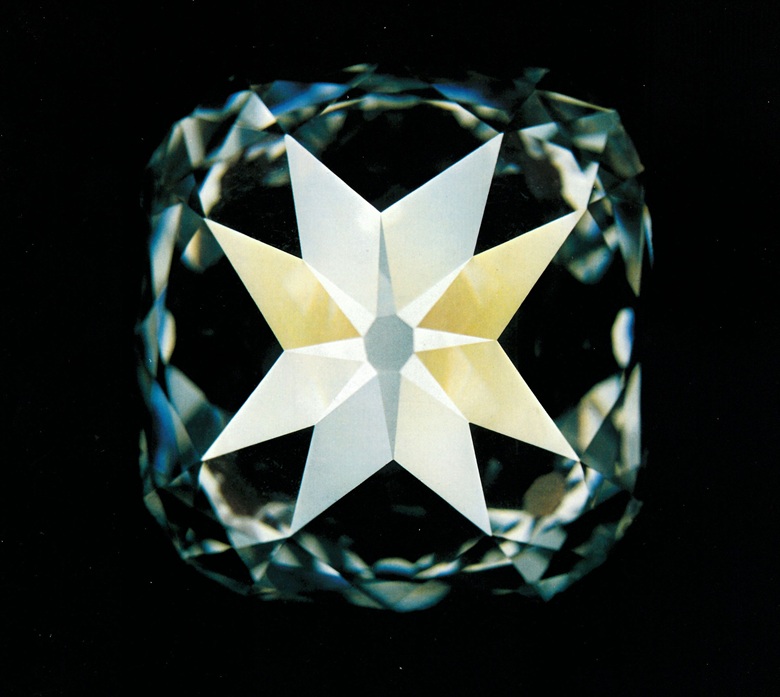

Some years earlier, Jacques had sent a trusted salesman to Baghdad to negotiate the purchase of several important gemstones. On his arrival, the salesman had been informed that the sale had to be conducted secretly and that he was forbidden to telegraph any details back to London. All he was allowed to say was that he needed a large amount of money to be sent over as soon as possible. Trusting his employee, Jacques approved the sum and had it wired over without delay. For such a large price, he supposed, Cartier would be acquiring an enormous number of precious gems. But when his salesman re-turned, he had with him only a small pouch. Out of this, he brought one single gemstone. It was an emerald the size of a bird’s egg. Jacques was enthralled. As a gemstone expert, he marveled at the chance to see and hold one of the great emeralds of the world, a gem so magnificent it had once belonged to the Great Mughal. But as a businessman, he was dismayed. Years ago, before the Russian Revolution, they would have had no problem finding buyers wealthy enough to afford such a gem. But the 1930s was a very different era. The only option for Cartier to make their money back was to cut the emerald in two and re-polish each half into a gleaming new stone. Though it pained Jacques even to consider splitting such a fantastic gemstone, he had to think of the business. One polished half ended up being sold to an American millionaire and the other, at 19.77 carats, became the centerpiece for Wallis’ engagement ring.

As with many of the jewels he bought for Wallis, the King had asked that Cartier engrave it with a personal message. This one read “WE are ours now 27 X 36.” He proposed on October 27, 1936, the same day Wallis was granted her divorce from Ernest Simpson.

So Jacques – and Cartier London – were caught in the midst of this famous episode in history?

Yes, I love how this episode illustrates the importance of a jeweller’s discretion – how a jeweller may be privy to secrets that even families don’t know about each other, in this case, the Royal Family. Jacques was, on the one hand, working on tiaras for the upcoming planned coronation of King Edward VIII while also working on the ring that would lead to his abdication. In the end, the coronation set for the summer of 1937 would still go ahead, but it would be for a different King than the one the world had been expecting, King George VI. Because once Wallis had the ring on her finger, the British Prime Minister told the monarch that the British public would never accept a divorced woman as their queen. “I think I know our people,” he said. “They will tolerate a lot in private life, but they will not stand for this sort of thing in a public personage.” In a series of meetings, he clearly spelled out Edward’s options: either renounce Mrs. Simpson or abdicate. In a poignant radio broadcast from Windsor Castle, the King announced his abdication and left Great Britain bound for France.

From then on, it would be Cartier Paris which would have the lion’s share of the couple’s jewellery commissions (her most well-known pieces would include a multi-gem flamingo brooch, an amethyst and turquoise necklace and the iconic big cat jewels).

In the 1930s, Cartier London was known for necklaces, and for its topaz and aquamarine jewels– why was that?

Rectangular, hexagonal, square and circular-cut aquamarines, circular and baguette-cut diamonds, platinum, may be worn as a necklace or applied to fitting and worn as a tiara, 16 ins., circa 1935, signed Cartier London, numbered. @Christie’s Magnificent Jewels, New York, 5 December 2018.

This was a creative and prolific period for Cartier London, especially for big necklaces – although sadly, many of the necklaces have since been broken down and haven’t survived into the modern period. The head of the design studio, Georges Massabieaux, worked with designers like George Charity and Frederick Mew (Mew was responsible for many of the firm’s more innovative geometric designs). In 1935, the London team was joined by the talented artist Pierre Lemarchand, who moved over temporarily from Cartier Paris. He got along particularly well with Mew, both great admirers of each other’s work, and he would go on to design many of Cartier’s animal jewels during and after WW2 (he was the man behind the famous “bird in a cage” brooch during the occupation of Paris and the panther jewels for the Duchess of Windsor).

Reflecting the difficult Depression economy, Jacques prioritised the use of semi-precious stones, which were not only considerably more economical, but also readily available in a variety of geometric cuts. This gave the designers the opportunity to come up with an almost architectural look in accordance with the fashions of the time. Topaz was generally combined with diamonds or gold: “The only requirement,” Vogue would explain in its October 1938 issue, “is that topaz jewellery must look as important as if it were emeralds or rubies. That is the way Cartier has treated it.” Often clients would request matching jewels: When the debutante Lady Elizabeth Paget was photographed for Harper’s Bazaar in January 1935, she wore “Cartier’s magnificent parure . . . of light and dark topaz,” comprising necklace, bracelet, shoulder clip, and large pendant earrings”.

But it was the combination of diamonds with aquamarines that Jacques particularly liked. It created, he felt, a look that was fresh and elegant and suited everyone from royalty to trendsetters. His clients agreed, as did many visiting Americans who ordered their jewels from his branch.

Of geometric design, set with oval, baguette and kite-shaped aquamarines and circular-cut diamonds, signed Cartier, fitted case stamped Cartier. @Sotheby’s London, Fine Jewels, 16 July 2014

I was told by my grandfather the behind-the-scenes story of how the Cartiers put together these semi-precious stone collections. It was important—if they were to source good stones at reasonable prices—that neither the dealers nor their competitors caught on to their buying patterns. After deciding on a particular gemstone, the brothers bought them under the radar over several months, or even years. Assuming it was topaz, they would buy topazes when different gemstone dealers came to present their wares, but never too many at one time or from the same dealer. The idea was that over the course of a couple of years, they would have acquired enough highest-quality topaz to make an impressive collection for a season. And then, by showing topaz necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and bandeaux in their windows, they would make the topaz the gemstone du jour. By the time their competitors tried to copy them, not only would there be very few high-quality topazes left on the market but also the dealers would have hiked their prices and it would become almost impossible for another jeweler to create a topaz collection on anywhere near the same scale.

I read that Jacques suffered from ill-heath, eventually passing away before his brothers despite being the youngest?

Yes, Jacques continued to work in London and travel East throughout the 1930s but he suffered from ill-health as a result of weak lungs (during WW1 he had suffered from tuberculosis and been gassed at the Front). During a 1935 work trip to India with his wife, for example, instead of settling into their usual sea-view suite on arrival, Jacques had been rushed to the hospital. “Jacques has haemorrhages on arrival Tajmahal Hotel Bombay,” Nelly had telegraphed her husband’s brothers in fear. “Good doctor and nurses. Will keep you posted.” Fortunately he recovered that time but his health had taken another beating and those weak lungs remained a worry always in the background.

To manage his health, Jacques was advised by his doctors to spend time in the mountain air of Switzerland so he and his family spent the winters in the fashionable Swiss mountain resort of St. Moritz. Villa Chantarella, the chalet they rented each year next to the large hotel of the same name, became a home away from home. “Here we are again on top of the world in our Noah’s ark full to the brim of growing ones,” Jacques wrote to Pierre one Christmas, explaining how all four children were out on the slopes with their friends while he was inside in the warm working on designs for an upcoming exhibition. The ski resort was also good for business and Jacques set up a St. Moritz seasonal Cartier branch. Enticingly located next to the famous Swiss confectioner Hanselmann, Cartier’s new showroom in the mountains attracted a fair number of window shoppers over the few months it was open each year. Clients who visited the ski resort at the time included everyone from the the Aga Khan III and Coco Chanel to Hollywood stars like Gloria Swanson and Douglas Fairbanks to to businessmen like Henri Deterding, “the Napoleon of Oil,” who bought the famous Polar Star diamond from the St Moritz branch.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, Jacques’ health had significantly deteriorated. Believing he should be in his native France in war time (despite the fact he shouldn’t have really travelled from England with his ill health) Jacques spent his last months in Hôtel Le Splendid in the spa town of Dax, in the south-west of France. Sadly, he wasn’t able to receive the medical care he needed there during wartime and passed away at 57 years old.

One of his last deeds was to ask his close friend, the designer Charles Jacqueau, to train my grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier in design. For Jean-Jacques, it was a great sadness he would never be able to work alongside his father in the business, but like his father he was also an artist at heart and grew to love the design and gemstone areas of the business. He took over Cartier London in the 1940s – when the pre-war era of big necklaces and diamond tiaras had been replaced by an age of austerity and a debilitating 125% luxury tax on jewels. Just as his ancestors had done, he had to drastically change tact once again in order to keep the business afloat… but that’s a story for another time…

***

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores. You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

Editorial update 12 April 2025

Cartier Exhibition until 29 October 2025

V&A South Kensington

Cromwell Road, London SW7 2RL

Tickets: vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/cartier

An Art Deco Aquamarine Diadem by Cartier London,

platinum 950, diamonds total weight c. 4 ct, aquamarines total weight c. 70 ct, signed Cartier London, reference no. 4423, workmanship c. 1930-35 @DOROTHEUM

The Dorotheum Auction Week was crowned by the sale of a rare Art Deco diadem for a sensational 582,800 euros on 10 June 2020.

The diadem was estimated € 34.000 – 70.000.

The diamond and aquamarine diadem can also be worn as a necklace.