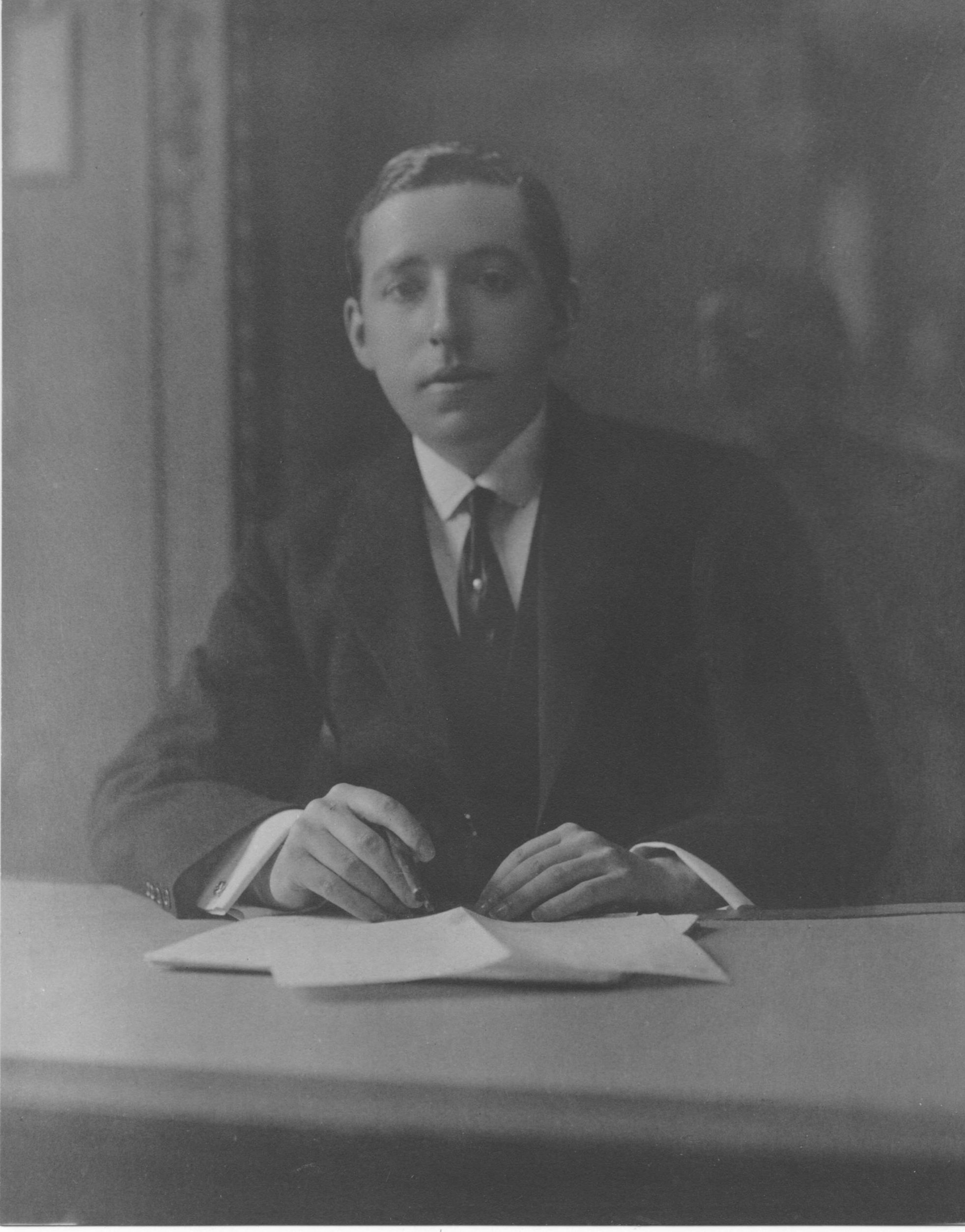

“He lived for design”: Jacques Cartier, the lesser-known brother

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Cartier recovered and told by his great-granddaughter – Part I

The history of Cartier in the first half of the 20thcentury is largely the story of the three Cartier brothers. Up until now, one of them has remained in the shadows: the youngest, Jacques. His elder brothers (Louis and Pierre) have been more widely discussed: Louis, who ran Paris, is often celebrated for his creative contribution to the jewellery world. He popularised the use of platinum as a mount in large diamond jewels and was the genius behind iconic pieces like the Tank watch. In America, there have been exhibitions and catalogues about Pierre and the Cartier New York business he founded. But Jacques has not been as widely discussed because there was less publicity known about him.

More recently, that changed when the discovery of a trunk of long-lost family letters prompted Jacques’ great-grand-daughter to delve into the untold story. Francesca Cartier Brickell has spent the last decade researching and writing about four generations of her family for a new book, “The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family behind the Jewelry Empire”.

I spoke to her last week to find out more about the life of this remarkable man. I am honored that Francesca Cartier Brickell has reserved for Property of a Lady this first exclusive interview in the French media !

Francesca, tell us about Jacques: what he was like and what was his role in the firm?

My great-grandfather Jacques was the youngest of the three Cartier brothers – born in 1884, he was almost ten years younger than Louis and still at school when his elder brother joined their father Alfred in the family business. Growing up, Jacques didn’t actually see himself as a jeweller: he was a gentle, artistic soul who felt a calling to become a Catholic priest. His family, however, had other ideas – his brothers told him his duty was with their fraternal trinity rather than a life spent in worship of the Holy Trinity! And so in 1906, at 21 years old, after completing his education and military service, he joined the family firm. First up was an apprenticeship in Paris where he worked in all the departments but discovered a particular passion for design and gemstones.

In terms of his contribution to the firm, Jacques was something of an all-rounder. As I explain in this Youtube video, whereas Louis was focused on the creative side (hiring designers and insisting the firm create unique pieces in the ‘Cartier Style’) and Pierre threw himself into the business side (opening branches in London and New York, traveling to Russia to meet suppliers and open an early a ‘pop-up’ shop for the Christmas season in St Petersburg), Jacques became a connoisseur of gemstones, a respected designer and a salesman who inspired great loyalty among his clients. In fact it was one of these loyal clients who wrote his obituary when he passed away: I discovered it in an old yellowing Times newspaper kept safely in the family trunk of letters all these years and I think it’s worth sharing here as it really sums him up – Lady Oxford, wife of the former Prime Minister Asquith, wrote “Jewellers are not always great artists, but this was not the case with M. Jacques Cartier. He was rarer than a great artist, or designer in precious stones: he was a wonderful friend. Completely unself-seeking, courteous to strangers, gay, kind and the best of ambassadors between the France which he loved and the England which he admired.” I was very moved to discover that because while I had grown up hearing how wonderful Jacques had been as a father, this showed the high regard in which he was held by those outside the family as well.

As I explore in my book, “The Cartiers”, the strength of Cartier in the early 20thcentury was down to all three brothers: their magic mix of complementary talents, their unbreakable bond and their shared ambition to build “the leading jewellery firm in the world.” They also had something that their grandfather (who had founded the family business in 1847) and their father Alfred had lacked: scale. There were three of them (‘three bodies, one mind’ as a contemporary of them once said), and with three they could divide and conquer. Taking a map of the world, my grandfather told me how they literally split it between them with a pencil: Louis took Europe, including the firm’s Parisian headquarters; Pierre took the Americas (he would go on to open the Fifth Avenue branch in New York) and Jacques took responsibility for clients in Britain (he would run the London branch) and the British colonies, most significantly India.

Tell us about the trips Jacques made to India, especially the first one – how did they come about?

Well, India was considered the jewel in the British Crown. Home to the Maharajas, some of the best jewellery clients on the planet, it was also the gem trading capital of the world. Jacques went on many business trips there over the years – both to buy and to sell jewels – but those trips weren’t just work for him, he came to truly love the country and its people (you can see more of Jacques’ trips to India in a behind-the-scenes video I made on Youtube).

Reading Jacques’ Indian diaries, I found it fascinating to realise how those trips had inspired many of Cartier’s creations in the 1920s and 30s. Wherever he went – from Indore, to Calcutta, to Hyderabad, to Delhi to Mumbai – he sketched and wrote about things that interested him along the way. He might note how the shape of a temple could be transformed into a brooch or how a simple lace acorn pattern he had spied in a crowded Indian bazaar had given him the idea for a diamond necklace. He had a great respect and admiration for the country and its culture – when he visits a temple, he writes: The carving of the stone … show a superior art. The ten centuries that preceded our era are one of the most wonderful periods in the history of the world. India’s share in the intellectual discoveries of these times was paramount”.

Platinum, diamonds, engraved sapphire vase, engraved rubies and emeralds. Courtesy of Olivier Bachet. @Palais Royal Collection

Jacques was 27 years old when he first visited India in 1911. Still unmarried, he had been working at the family firm for five years but he had lived a relatively sheltered life, only venturing overseas from Paris to London to head up the Cartier shop there. This was a far more adventurous mission: 3 weeks on a boat from Marseilles to Bombay, via Egypt, the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden. They left in the Autumn of 1911 in order to reach Delhi for the much-anticipated Delhi Durbar taking place that December. All the Indian princes would be present in Delhi to pay their respects to the new King George V and Queen Mary – and jewels would be centre stage. The Cartiers’ plan was that if Jacques was also there, he could meet multiple potential clients all in one place and hopefully also pick up the odd invitation to then visit them in their palaces.

But just to step back a moment, reading through the letters between the brothers, I discovered that surprisingly (to me at least) the main reason for Jacques taking that initial long boat trip East was not just to visit India but actually to investigate the pearl trade in the Arabian Gulf. At this stage, before the explosion of cultured pearls onto the market, natural pearls were extremely rare and valuable (to give an idea of the value: in 1917 Cartier exchanged a pearl necklace for its Fifth Avenue headquarters). No surprise then that pearls formed the lion’s share of Cartier’s income or that Cartier was keen to try and buy the pearls at source in order to ‘brand’ itself as a ‘Supplier of Pearls’ (a heading they proudly used on their invoices).

Given that many of the most sought-after and expensive white pearls were fished in the Persian Gulf, Louis sent his younger brother there on a mission that Jacques explains in a December 1911 letter: “My dear Louis, if I have understood correctly, the most important mission bestowed on me during this trip to the East was to investigate the pearl market and to report back on the most effective way for us to purchase pearls.”

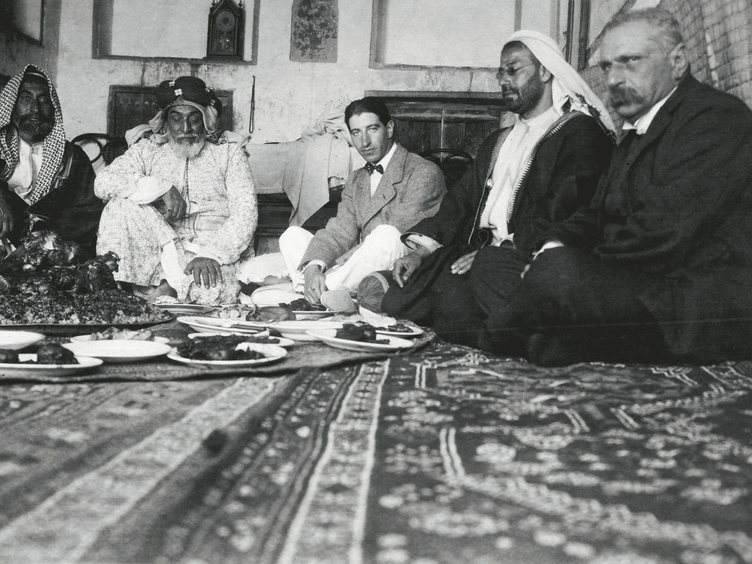

The Cartiers felt that if they could meet the Persian Gulf pearl sheikhs on their own ground and begin to forge professional relationships with them, then they might be able to cut out some of the middlemen involved in the pearl trade. Most significant among Cartier’s competitors when it came to pearls were the Parisian-based Rosenthal brothers who were unique in having gained the pearl sheikhs’ loyalty and trust – and therefore had the monopoly on the pearl trade in the West, much to Louis’ intense frustration! So, on this first trip out to the East, Jacques’ traveling companion was the top Cartier pearl expert, Maurice Richard, because he needed a specialist with him who truly understood how to value pearls. After visiting the Delhi Durbar and meeting with clients in India, the pair of them – along with a translator they’d hired in Bombay – took the boat to Bahrain in March 1912. The adventure that awaited them is fascinating – meeting the pearl divers, trading with the sheikhs and the shock of eating meals sitting on the floor without cutlery! – but that’s a story for another time..

So visiting India wasn’t actually the main aim of that first trip?

I would say that, initially, it was more a by-product of that primary mission, but it became much more than that – and by the 1920s and 30s certainly, the Cartier Indian connection became absolutely fundamental to the wider business. That first trip to the Durbar though didn’t go as smoothly as planned. Much like a traveling salesman, Jacques had taken with him suitcases of jewels to tempt the Maharajas: delicate, garland-style necklaces, brooches and head ornaments. However, he soon discovered that in India it wasn’t the women who were buying the jewellery, it was the men. And they were not buying for their wives or their lovers, like they were in Europe. They were buying for themselves. So after going to all that effort of taking such valuable jewels out there – insuring them, declaring them on arrival in Indian Customs, carrying them around the country with him and so on- to his dismay, Jacques found that the most orders he received were actually for the simple pocket watches that were all the rage in Paris at the time. Although the maharajas had some of the most splendid, exotic, envy-inducing gems on the planet, they were also – so Jacques discovered –simply keen to keep up with the fashions of the West.

Signed Cartier, Paris, circa 1910. @Christie’s

So did the Durbar turn out to be a disappointment?

Well, the Durbar itself was a bit lackluster when it came to sales, but it did enable Jacques to meet many of the ruling princes in their majestic tents across the Durbar encampments, including the Maharaja of Nawanagar who became a great friend. And from those initial meetings, he received invitations to visit them in their palaces across the country: sometimes he stayed in opulent palaces but at other times he was simply a traveling salesman sleeping on rough matting on the floor in basic station houses. As he travelled through the country, Jacques wrote extensive travel diaries, some of which I have based my travels on as I wanted to revisit many of the places for myself.

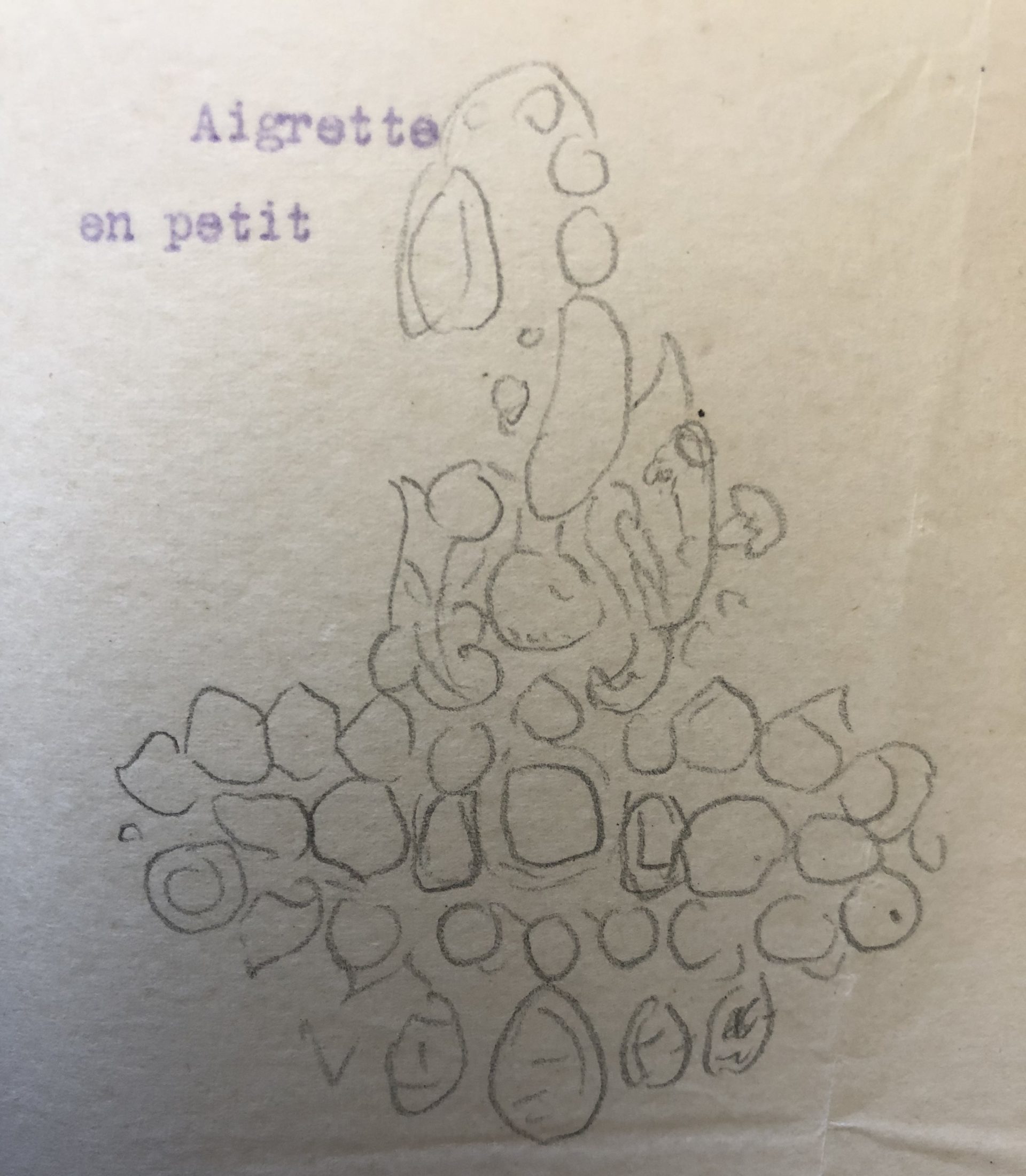

In Baroda, for example, Jacques talked about meeting the Gaekwad and Maharani in 1911 and described how he was asked to come up with designs for the resetting of the crown jewels. He spent days furiously sketching in the palace before the local court jewellers grew jealous at his presence and made him leave without securing the commission! The Maharani, however, managed to quietly give him some of her jewels to remodel. For me, it was wonderful to visit Laxmi Vilas Palace a century later and share some of Jacques’ sketches with the current Maharani Radhikaraje. When I showed her this pencil sketch from Jacques’ diary for example, she was immediately able to identify it as the diamond aigrette pictured below. That was exciting – one of those moments when past and present collide.

But Jacques was not just in India to sell jewels. As the family gemstone expert, he was always on the lookout for gems to buy as well and when he travelled, he would take his pouch of trusty “killer stones.” These were the most perfect examples of precious stones that he owned: a Burmese ruby, a Kashmir sapphire, a Colombian emerald, and a Golconda diamond. He would use them as comparison stones when buying from dealers in shaded crowded markets or from gemstone mine owners next to the sapphire pits under the bright sun or from royalty in palaces – it meant he was assured of a perfect comparison stone whatever the light was like at the time. And as he never knew when the opportunity would arise on his travels to buy gems, those killer stones were a simple way of making sure he was always prepared. When he visited the palace of Patiala in 1911, for example, the Maharaja wanted to buy a special Cartier pearl but instead of paying for it with cash he proposed exchanging it with some of his own jewels so Jacques found himself unexpectedly valuing gems instead of simply selling them.

In time, thanks to Jacques’ buying expertise and his loyal links with the gem dealers and palaces, Cartier became renowned as the jeweller with the best coloured gemstones in the world.

Tell us about WWI – did Jacques fight?

Yes – he felt a strong sense of duty to his country: my grandfather explained to me that for his father it had been “Country, Family, Firm” in that order. When WWI broke out, Jacques was actually ill with tuberculosis and sent to a sanatorium in Switzerland – but instead of being relieved to be avoiding the fighting, he just wanted to receive the best treatment as fast as possible so he could rejoin his regiment and fight alongside his fellow countrymen. His brothers took safer jobs (Pierre as a chauffeur to a general, and Louis in several office posts) and they urged Jacques to do the same. He had the perfect excuse, they told him, it would be easy to have a doctor sign him off as unfit for service at the Front given his weak lungs. But Jacques refused: he saw no reason why he should be treated any differently from his fellow soldiers. After recovering from tuberculosis, he joined his cavalry regiment at the Front, only to be gassed and sent to another hospital – this time in Lucon – for several weeks. Once he had recovered for the second time, he re-joined his regiment at the front again – much to his brothers’ exasperation – leading them into battle. For services to his country, he received the Croix de Guerre but his lungs never really recovered from the gassing and in later years, he would describe himself as living a ‘half-life’ lacking energy and struggling for breath.

After the War, the world was a very different place. Years of fighting had taken their toll on Europe and the balance of wealth – and with it Cartier’s key clients – shifted across the Atlantic. Jacques went to help Pierre with the Fifth Avenue branch (they felt they needed two family members out there to really grow the business and meet demand) before moving to England a few years later. Together with his wife Nelly and their four children, he settled in Milton Heath, a large country house in Dorking, Surrey. Every morning, as his son took the horse and trap to school, Jacques would travel the thirty miles in his chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce up to Cartier London in Mayfair. He had moved the London headquarters to 175 New Bond Street in 1909 (previously it had been a much smaller showroom below the Worth shop around the corner on New Burlington Street) and it was an impressive building. Outside, a doorman stood to attention in front of the royal warrants on the pillars, while inside walls were draped in rose-pink moire, candelabras hung from the ceiling and mirrors reflected discreet touches of gilt. It was, according to a designer who worked there in the 1920s: a “near replica of Cartier in Paris, but perhaps even more upstage than the establishment in the rue de la Paix – having an added barrier of English reserve. Anyone would think twice before entering.”

This interview continues with “Cartier London : The roaring 20s”

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores.

You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

Editorial update 12 April 2025

Cartier Exhibition until 29 October 2025

V&A South Kensington

Cromwell Road, London SW7 2RL

Tickets: vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/cartier

Francesca Cartier Brickell, Photo Credit: Jonathan James Wilson