Cartier London: The roaring 20s

At the very heart of the Cartier saga: the extraordinary life of Jacques Cartier recovered and told by his great-granddaughter Francesca Cartier Brickell – PART II

Pour lire cet article en Français, veuillez cliquer sur ce lien

To read part I « He lived for design : Jacques Cartier, the lesser-known brother », click here

So Francesca, tell us more about the Cartier London operation in the 1920s: what was Jacques’ involvement in the design side?

An artist himself, Jacques enjoyed being involved in the creative process. He got along particularly well with the team of designers, who respected him for his love of their trade.

Courtesy of Olivier Bachet @Palais Royal Collection

In early 1921, he and his brothers set up English Art Works, the London workshop. Until then, Cartier London had relied on the Paris workshops that supplied 13 Rue de la Paix for its stock. The setup had worked well enough for a time, but as demand increased, it became apparent London should have its own team on the ground (as in New York). Félix Bertrand, a talented jeweler who had proved his skills setting up the American Art Works workshop under Pierre, was sent over to do the same in London. Under his leadership, and that of a fellow Frenchman, Georges Finsterwald, a team of skilled mounters, setters, and polishers were hired.

Of course, building a fine jewelry workshop didn’t happen overnight. The Cartiers sought to hire top master craftsmen, at considerable expense, and then relied on them to teach the young apprentices. The firm took on about five or six apprentices a year, mainly Englishmen (Jacques felt strongly it was his duty to offer opportunities to the English workforce), of which only one or two made it through the first year of a six-year traineeship.

The creations made under Jacques quickly found favour with the English aristocracy, both for their original designs and for the high quality of the craftsmanship. I love the example of a carved emerald necklace made for a maharaja: those emeralds were so fragile that the craftsman tasked with setting them was given 48 hours off work beforehand so he was entirely relaxed because any slight shake of his hand could cause the precious gems to crack!

Signed Cartier London. @Christie’s London, Important jewels, 12 dec 2012.

There’s a fun account of Jacques as a boss by one of the apprentices: “Jacques was then what we called a gentleman. He was excitable, kind and lived for design. I learnt that everything grows from something that grew before, and the room contained a library of things that had gone before: Chinese carpets, Celtic bronze-work, Japanese sword hilts, arabesques…”. This is the basis of the family motto “Never Copy, Only Create”, which I discuss in the book (and in this Youtube video).

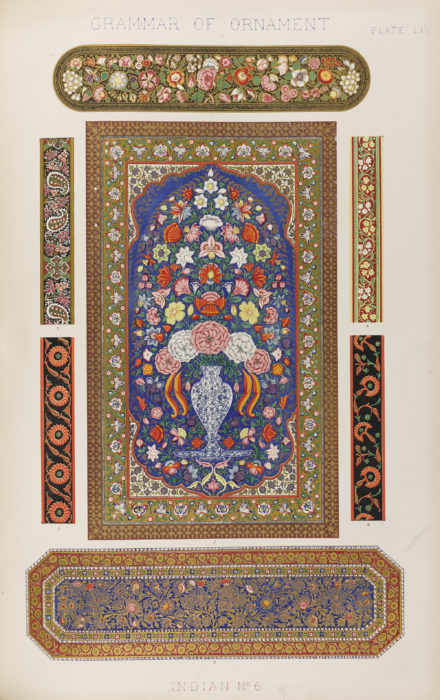

Essentially the idea was that anything and everything could and should be used for inspiration, except for existing jewelry. The brothers were avid readers of Owen Jones’ book, “The Grammar of Ornament” which had plates exploring the design principles behind the architecture, textiles, and decorative arts of contrasting cultural periods (for example, the Arabian, Turkish, Persian or Indian styles).

To what extent do you think Cartier London had its own identity in Jacques’ time?

Certainly, by the late 1920s, Jacques had succeeded in creating a distinct identity for Cartier London, so much so that he decided to buy his two brothers out of the branch. But the three branches remained intertwined, as the three brothers continued to share everything from designs to clients to gems. And though Jacques was living in England and running a British company, he never lost that sense of duty to his native France, even becoming head of the Alliance Française in London.

Jacques was not particularly social by nature but he became well-networked within British high society, thanks in part to being a savvy marketeer. He would offer jewels as prizes for charity events or lend jewellery to socialites for big events, such as the Jewels of the Empire Ball at the Park Lane Hotel, the hot invite of the day. Most evenings after work, he and his wife Nelly would dine out in London with clients, visiting French dignitaries and friends.

The 1920s were an exciting time for growth, with new money competing with old and Jacques’ acquaintances included a growing number of financiers, industrialists, and entrepreneurs, from Victor Sassoon to Captain Alfred Lowenstein (before his tragic – and mysterious – early death falling from his private plane). Clients of the London branch also covered the spectrum of English high society, from aristocrats and heiresses such as Lady Sackville (known to pop in to buy gifts for her daughter, the writer Vita Sackville-West, after their momentous rows) to a new generation of “bright young things”.

Satirized in Nancy Mitford’s and Evelyn Waugh’s novels, this fast-living wealthy bohemian group had expense accounts at Cartier and danced all night in diamonds. Their number included Nancy Cunard, Lady Abdy, Lois Stuart, the Guinness sisters, and even Daisy Fellowes whose famous Collier Hindou necklace was made in Paris but who – like many clients – shopped in all three Cartier branches: in London, she bought the 17.47ct Youssoupoff Tête de Bélier (ram’s head) pink diamond which was said to have later inspired Elsa Schiaparelli’s signature shocking pink.

Tell us more about Jacques’ wife, Nelly?

Nelly was great fun, a larger than life American heiress who was – on the surface – the opposite to Jacques. A Protestant who had been married before, she was living in Paris’ Avenue Henri Martin with her parents and young daughter when she met Jacques for the first time. It was pretty much love at first sight – or first meeting at least – but Nelly’s father, John Harjes, a prominent banker and the partner of J.P. Morgan (in fact, John Harjes’ bust still sits proudly in the lobby of the Place Vendome J.P.Morgan bank today) did not approve of his daughter marrying a jeweller. So he set a condition: if Jacques really wanted to marry Nelly he must prove his love by staying away from her for an entire year. Jacques agreed without hesitation. 365 days later, he returned to ask for her hand in marriage. Mr Harjes agreed and Jacques promised there and then that he would never touch a cent of Nelly’s money.

The couple adored each other. In the 1920s and 1930s, Jacques went back to India regularly and Nelly would accompany him on the trips (she travelled with 18 suitcases so she took along her personal dresser as well!) They took their chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce all the way from London but it wasn’t always plain sailing: there were times when they had to cross streams on rafts or when the Rolls had to be dismantled to make it over rocky terrain – and then put back together again on the other side! Accommodation en route varied a large amount too: one minute they might be sleeping on the floor in a basic station house, the next luxuriating in the comfort of a maharaja’s palace.

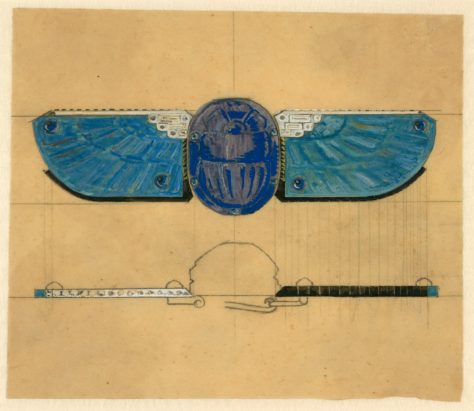

Nelly was also a great adventurer in her own right, always up for new travel in exotic places. Jacques called her wanderlust the “Va Va” as she wasn’t good at sitting still : she wanted to « go go » And when she returned from those explorations – she often travelled with her best friend, Madame Fournier – he loved hearing all about them: “raconte moi ton cinema” he would say, sitting by the fire in their sitting room as she filled him in on stories from the other side of the world. When she returned from Egypt, for example, she brought back small momentos. Jacques kept a bright blue scarab beetle made from fabric/feathers: remarkably similar to the ones Cartier would later create as jewels.

Is this where the idea for Egyptian revival jewelry came from?

Well, Jacques had first visited Egypt in 1911 so they both knew the country, and there was something of an Egyptian craze in the early 1920s. When Egyptologist Howard Carter announced to the world in 1922 that he’d unearthed an opening to Tutankhamen’s tomb, and with it artistic treasures of a long-shuttered mysterious past, Egyptomania swept Paris, London, and New York.

After the deprivations of war, escapism was more welcome than ever, and ancient Egypt was suddenly all anyone could talk about. Fashion designers found inspiration in motifs like lotus patterns and the vibrant colors of Egyptian paintings. Women heaped on the black eyeliner and put their hair up to more closely resemble the glamorous beauties of the past. Bright cocktails with names like King Tut became the drinks du jour and Egyptian-themed parties were all the rage.

Jacques was similarly inspired. As photographs and articles made their way to the West, Jacques carefully cut them out of newspapers and folded them into his small black leather diary. Not many things made it into that diary, but Jacques felt that this momentous discovery had revealed works of art on “a plane of excellence probably higher than has been reached in any subsequent period of the world.”

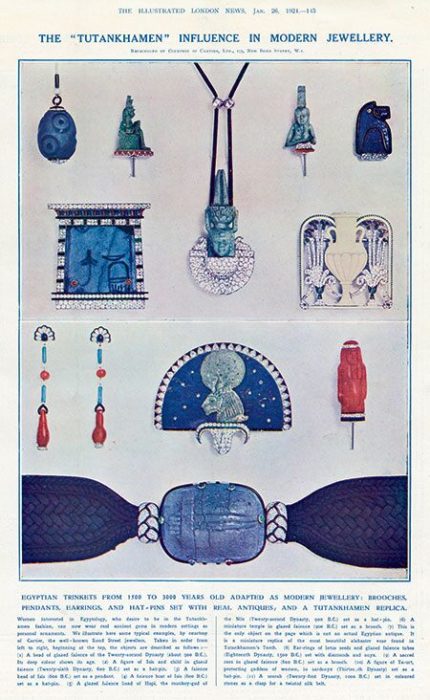

This led Cartier London to create some truly stunning Egyptian Revival style jewels. In January 1924, there was a full page spread in The Illustrated London News Cartier London’s Egyptian creations, announcing that “Women interested in Egyptology, who desire to be in the Tutankhamen fashion, can now wear real ancient gems in modern settings as personal ornaments.” These one-of-a-kind pieces incorporated genuine antique treasures, sourced by the Cartier brothers from European antiques shops and Eastern bazaars.

The challenge was keeping the purity of the ancient style while updating it for a modern audience. This wasn’t to be a whimsical attempt to follow the fashions of the day, it was deeply rooted in authenticity. For a deep blue bead from 900 B.C, Jacques chose to enhance its color with the smallest amount of diamond and onyx on its top and base, and to make it into a simple pendant. A figure in a bright blue crescent-shaped glazed faïence was brought into focus with a subtle border of diamonds and onyx, and three-thousand-year-old stone carvings were framed in black onyx. The focus was on a simple dressing up— nothing fanciful. It had to be true to the original style and stay classic. These were ancient artifacts that had survived thousands of years—they should not be turned into elaborate pieces that might soon go out of fashion.

What about the Tutti Frutti jewels – how was Jacques involved with those?

Jacques saw the world with an artist’s eye and India made a particularly strong impression on him: “Out there everything is flooded with the wonderful Indian sunlight.. one does not see as in the English light, he is only conscious that here is a blaze of red, and there of green or yellow”. After his trips, he would meet with his eldest brother Louis and the head designer in Paris, Charles Jacqueau, and they would discuss ideas for an Indian-style of jewellery. `

This would take many forms – from carved emerald pendant brooches (like the one bought by Marjorie Merriweather Post from Cartier London) – to the now iconic tutti frutti jewels where vivid rubies, emeralds and sapphires would be boldly combined together. The colored stones might be faceted, cabochon, or carved, and the motif was often based on nature but the most important characteristic of those gems – for Jacques – was their colour. They had to be bright, bold and striking. That was the secret behind the powerful effect of the tutti frutti jewels (along with the intricate designs and exquisite craftmanship).

And what I found particularly interesting in my research was that although those Indian-inspired jewels often reach record prices at auction today (it was fun to be involved on the online Sotheby’s sale of a Tutti Frutti bracelet last month that broke records when it sold for $1.3m!), in reality the carved gems that Cartier used back then were far less expensive than larger precious gemstones (partly because any flaws could be carved out). So actually, during the 1930s they became quite good “Depression-era jewels”. I show some more examples of that style in this Youtube video.

Do you have any favourite Indian-inspired pieces?

It’s hard to say – and I am guilty of changing my mind regularly! A wonderful example of a Cartier London « tutti frutti » piece that I saw again just before lockdown at the V&A Museum (where it sits on permanent display in the jewellery gallery for those who would like to see it too!) is the Mountbatten bandeau. It’s stunning – delicate and bold at the same time and a brilliant design made to either sit flatteringly on the forehead or be split into 2 bracelets. (3 jewels for the price of 1 really!).

In my research I dived into the background of those 1920s bandeaus and discovered that in 1928, Jacques wrote to his brother Pierre telling him about a London charity fashion show that he was working on with notorious society heiress Lady Cunard. “The idea”, Jacques explained,“[was] to show what women with short hair can wear, both now and when they start to grow their hair again.” The days of pre-war big hair up-dos and heavy tiaras were over and the Cartiers quickly adapted their offerings to include a vast array of head-dresses, bejewelled hair clips and diamond crescents and circles to decorate tightly shingled heads.

The colourful Mountbatten bandeau (as it later became known) was one of over 100 pieces that Cartier made for the fashion show but it was snapped up for £900 before it even made it to the runway. The buyer, Edwina Mountbatten (1901-1960), was a strong stylish and well-connected woman who knew what she wanted when she saw it. She would also, rather aptly given her choice of the Indian-inspired headdress, go on to become the last Vicereine of India.

Did Jacques have a favourite Indian client?

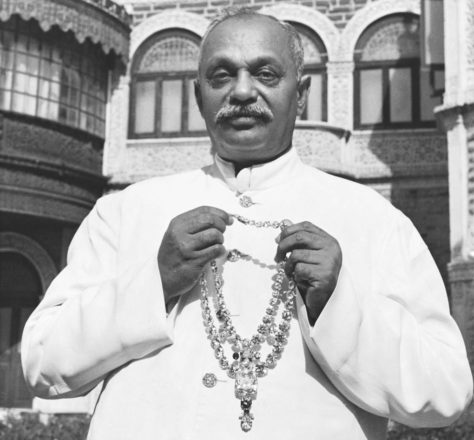

Well, over time, Jacques built a relationship with many of the Indian princes, from the Maharajas of Kapurthala, Patiala, Indore, Baroda to the Nizam of Hyderabad. They chose to give their large commissions to Cartier not only because they appreciated the quality of the firm’s craftsmanship, but also because they trusted Jacques, and were appreciative of the time he had spent in the country. Of all of them, he was especially close to the Maharaja of Nawanagar. Better known as Ranji (short for Ranjitsinji), the Jam Sahib had been educated in England and was a well- known cricketer.

After Jacques’ initial trip to India in 1911, the two men often saw each other and became good friends. Jacques and Nelly were frequent visitors at his Indian palace: Nelly wrote home to her children in excitement after her first trip there in 1926 for Christmas: “I hardly know how to begin to describe the luxury we live in. Indeed what with one Rolls at our disposal and the suite in this palace built for the Prince of Wales visit (which he never came to see and hurt most frightfully His Highness as you can imagine).” After a Christmas banquet -“table decorations wonderful but no crackers or mince pies could make it a real Christmas atmosphere” – they enjoyed a “very very thrilling” panther shoot. Not very politically correct these days but interesting given the iconic Cartier panther motif!

Ranji, like many of the Maharajas, also travelled to England regularly and he would meet Jacques in London to discuss jewellery commissions or invite him and Nelly – plus the kids – to spend holidays at his Ballynahinch estate in Ireland. My grandfather recalled spending blissful summers there as a young boy, roaming free with his siblings over the enormous estate, with his Ranji as their generous host.

At the root of the jeweller’s and the maharaja’s close friendship was a sense of sharing the same values. Jacques described Ranji as “a Prince really princely in his taste as well as by the qualities of his mind and heart”. But that was not all: they also shared a love of gemstones. The stylish Indian ruler would happily wait decades for the most perfectly deep- red ruby or vivid green emerald. It didn’t have to be huge and show-stopping; he was far more interested in the quality and innate beauty of the jewel. Like a true collector, he would admire his gems even when alone, holding them in his hands and studying them under different lights just for the pleasure of it. The two men tended to agree on most things, but interestingly disagreed on the perfect colour of rubies –Jacques felt it should be deep red but Ranji preferred more of a purple hue.

Was there a favourite piece made for the Maharajah of Nawanagar?

The Maharaja Jam Sahib of Nawanagar became a very important client for Cartier, commissioning museum-worthy emerald necklaces and buying figurine mystery clocks. He had a truly incredible collection of stones. Jacques’ favourite commission of all was a diamond necklace. But not just any diamond necklace: this one took three years to make, as an increasing number of superb quality diamonds kept being added to the mix, so the design had to keep being adjusted to include them!

“Had not our age witnessed an unprecedented succession of world-shaking events,” Jacques would later write, referring to the cumulative effect of the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Depression, “such gems could not have been bought at any price; at no other period in history could such a necklace have come into existence.”

In the end, the necklace included the Queen of Holland – a blue-white 136.25 carat diamond- as well as fancy blue and pink diamonds and an olive-green brilliant diamond of 12.86 carats—“A rare stone, indeed!” Jacques had exclaimed when he saw it. When the necklace was completed, the overall effect was extraordinary, a unique cascade of colored diamonds.

My grandfather told me how his father had been a very modest man who rarely talked about himself but this was one piece he admitted being truly proud of creating: he called it “a really superb realization of a connoisseur’s dream.”

Sadly, after all the work that had gone into it, Ranji did not have much time to enjoy the necklace and Jacques did not see his friend wear it again. Just two years later, Ranji would die from heart failure. His nephew and successor, Maharaja Digvijaysinhji of Nawanagar, would follow in his uncle’s footsteps, becoming an excellent client in his own right and often asking Jacques to remount old family heirlooms in the Cartier style such as the tiger’s eye diamond sarpech in 1937.

This interview will be continued next week, when Francesca will be discussing Jacques’ role in Cartier London in the 1930sCartier London in the 30’s : A decade of contradictions.

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, “The Cartiers” is now available via Amazon or English language bookstores.

You can also follow her journey via Instagram (@creatingcartier) or on Youtube (@francescacartierbrickell).

A 1924 Scarab brooch with fragments of Egyptian faience. CARTIER, BROOCH, 1924. Faience, diamond (round old-cut), emerald, smoky quartz, and enamel. Vincent Wulveryck, Cartier collection. © Cartier. This brooch was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Past is Present: Revival Jewery. Exhibition from February 14, 2017 through August 19, 2018 @Museum of Fine arts, Boston